Should credit unions be taxed?

Taxing small banks and credit unions isn’t the answer. Jobs and efficiency are

- |

- Written by Mike Moebs

- |

- Comments: DISQUS_COMMENTS

For decades many bankers have wanted credit unions to pay taxes. "Prairie Economist" Mike Moebs suggests there's an attractive alternative to having IRS chase the bulk of the credit union industry.

For decades many bankers have wanted credit unions to pay taxes. "Prairie Economist" Mike Moebs suggests there's an attractive alternative to having IRS chase the bulk of the credit union industry.

“I am in favor of cutting taxes under any circumstance and for any excuse, for any reason, whenever it’s possible.”—Milton Friedman

Milton Friedman believed corporate income tax should be eliminated. His position was a corporation passes on the cost of taxes to the user in the form of higher–priced products or services. As a result, the consumer absorbs the cost of corporate income taxes.

During his tenure as Federal Reserve Board chairman, Ben Bernanke studied employment—most specifically, who created jobs. What the Fed found was that at least 60% of job creation came from small businesses, especially those with 25 or fewer employees.

With 24 million small businesses nationwide, it is easy to see how they create a majority of the jobs in the U.S. And these small businesses seek out community banks and credit unions for their lending needs.

Most small businesses will seek a line of credit for inventory or short–term cash pitfalls or seek financing for equipment or vehicles. The high costs incurred from lending are then passed onto the consumer in a similar way that a community bank passes taxes onto their borrowers.

In each case, the consumer takes the hit.

So, the real questions are: “Why do we tax banks?” and “Why do we want to tax credit unions?”

I know community bankers and some trade associations have long wanted to level the tax playing field vis-a-vis credit unions. I have a radically different solution in mind, and, once I lay it out, I would appreciate feedback in the comment section below.

It’s about more than jobs

Efficiency of financial institutions is an important taxation question. The basic axiom is that those companies that are most efficient in their operations should profit the most and be least affected by taxes. (This should be whether the entity is a bank, thrift, or credit union.)

The benchmark for efficiency is economy of scale.

Boone Pickens, oil magnate and financier, wrote about economy of scale in his 1987 autobiography, The Luckiest Guy in the World:

“It’s unusual to find a large corporation that’s efficient. I know about economies of scale and all the other advantages that are supposed to come with size. But when you get an inside look, it’s easy to see how inefficient a big business really is. Most corporate bureaucracies have more people than they have work.”

In banking, the “Too Big To Fail” group can also be characterized as operating at diseconomy of scale. This “Too Big To Fail” group epitomizes large inefficiency coupled with systemic risk, or the failure of one company in the “Too Big To Fail” club to take down a market, region, or even the country.

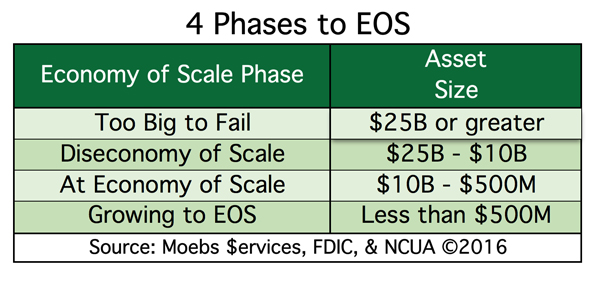

Studying Economy of Scale (EOS) for over 30 years has given us the ability to calculate the efficiency of financial services. When determining an operation’s efficiency, there are four general stages (per the table below):

1. Growing to Economy of Scale: Financial institutions with assets < $500 million.

2. At Economy of Scale: Financial institutions with assets of $500 million to $10 billion.

3. Diseconomy of Scale: Financial institutions with assets of $10 billion to $25 billion.

4. Too Big To Fail (Systemic Risk): Financial institutions with assets > $25 billion.

A simple plan: Tax inefficiency and create jobs with efficiency

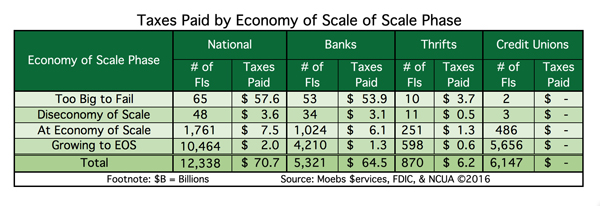

In 2015, banks and thrifts were taxed $70.7 billion at the federal level, comprising $64.5 billion (91%) paid by banks and $6.2 billion (9%) paid by thrifts. Credit unions are not taxed.

Asking how much in taxes is being paid by banks and thrifts at each phase of Economy of Scale delves deeper.

• Too Big to Fail companies pay $57.6 billion (82% of the total bank and thrift tax burden) in taxes, or a 30.4% tax yield, which is based on operating income.

• Financial institutions operating at the Diseconomy of Scale phase pay $3.6 billion (5%) in taxes, or a 29.4% tax yield.

• Financial institutions operating at Economy of Scale pay $7.5 billion (10%) in taxes, or a 20.7% tax yield.

And finally, institutions growing to EOS pay $2.0 billion (3%) in taxes, or a 16.3% tax yield.

Because many community banks (47.1%) are classified as Subchapter S corporations, they pay less in corporate taxes as a group. The owners of Subchapter S banks pay taxes at the individual shareholder level only and not at the corporate level.

This simple plan would retain the Subchapter S option.

The question then becomes:

Why are community banks and thrifts at the first two phases of EOS paying $9.5 billion in taxes?

The community financial institutions are vital in job creation, because a majority of small businesses go to them for their borrowing needs. With an easing of taxes, they could help create more jobs by providing more credit to small business at lower rates.

Job creation and paying for systemic risk

Banks, thrifts, and credit unions must be viewed as exactly what they are: financial intermediaries.

This is the go-between for borrowers and those with deposits or funds. For the economy to grow efficiently, small businesses, which provide and create the majority of jobs in the U.S., should have access to community banks who are free of taxation. Without paying taxes, they are able to offer a lower-cost loan to the small businesses.

Important to understand: This abolition of tax is only at the financial institution or corporate level, while owners and stockholders would still be taxed for dividends paid on a Subchapter S tax basis.

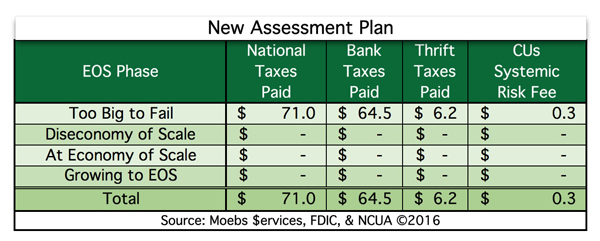

The Too Big To Fail group would pay the $9.5 billion in taxes currently incurred by financial institutions at or below their EOSs.

Along with that, Too Big To Fail would also pay the $3.6 billion currently paid by financial institutions at their diseconomy of scale. The $13.1 billion in taxes can be absorbed by the 65 belonging to the Too Big To Fail Club without a significant disruption to their profits. If straight-lined allocation was done of the $13.1 billion, this would only be about $200 million of additional taxes for each Too Big To Fail Club member.

Larger financial institutions facing higher taxes can reduce their tax bill by scaling back to operating at their economy of scale levels.

This can be done by focusing on and retaining functional areas in which they are more efficient. Inefficient operations, such as checking accounts and small business lending, can be moved to financial institutions at all other levels of the economy of scale. Those companies are growing to get to or are at the economy of scale in the depository business.

Getting away from politics

In order to avoid the political hailstorm of taxing credit unions, those credit unions that are in the Too Big To Fail group would be assessed for systemic risk. Effectively, they would not be taxed by the IRS and the assessments would be paid to the National Credit Union Share Insurance Fund, administered by NCUA.

Shadow Banking firms who provide alternative options for loans would also be taxed for circumventing the regulatory system that tries to prevent systematic and systemic risk.

Should any bank, thrift, or CU be taxed?

As the White House changes leadership and Congress starts a new session in January 2017, there are some crucial tax moves to consider:

1. Taxing financial institutions directly affects the consumer, who incurs the cost.

2. Majority of job creation comes from small businesses, who rely on community banks and credit unions for their lending needs.

3. The Economy of Scale phases can determine bank taxation.

4. Too Big To Fail group needs to be taxed for their inefficiencies coupled with systemic risk.

As Milton Friedman stated, any corporate tax is a way to indirectly tax the customer or user of the product or service.

The result of this Simple Tax Plan is an effectively level playing field for all financial institutions and the availability of more credit at lower costs to small businesses who generate jobs.

As I said earlier, I’d welcome your feedback. Please use the comment section below so we can all hear your thoughts.

Semper,

Mike Moebs

(Mike will respond to questions at [email protected].)

Tagged under Blogs, CSuite, Community Banking, The Prairie Economist, Feature, Feature3,