What does your checking service cost?

Efficiently operated financial institutions have lowest expenses

- |

- Written by Mike Moebs

- |

- Comments: DISQUS_COMMENTS

Balancing a checkbook may be an old-fashioned concept for some depositors, but for a bank maximizing the return of transaction-account service is something of a balancing act itself.

Balancing a checkbook may be an old-fashioned concept for some depositors, but for a bank maximizing the return of transaction-account service is something of a balancing act itself.

Only 18% of banks, thrifts, and credit unions operate efficiently, according to a Moebs Cost Study of 12,000 financial institutions. These efficient financial institutions manage checking at a much lower cost than organizations that are inefficiently operated.

Interestingly, the institutions that operate efficiently have an average checking cost of $175 per account, annually. Simultaneously, those institutions that operate inefficiently have an average annual checking cost that is almost double—$314 per account.

Efficiency is beyond just cost to operate. It also includes design of the checking account. This includes the type of checking accounts offered and the features the checking account has. Fewer checking account types and fewer features makes it easier for sales representatives to sell.

This trend is consistent within all asset size categories.

Looking at costs by bank size

Examining checking costs by asset size provides some very interesting characteristics. A constant trend seen throughout all depositories—bank, savings institution, or credit union—is that the number of checking accounts along with transaction volume increases with the institution’s size.

“Isn’t that a given?” you are thinking. Yes, but think beyond the obvious.

Volume is the big “invisible hand” of banking.

For example, how much interchange a type of checking account produces is very important as to types and features offered.

• Does a depository want transaction-oriented checking accounts?

• Or does it want sales-oriented checking accounts to cross-sell other services that are profitable. (This means the checking account can be a loss leader.)

• Or, does the bank want both?

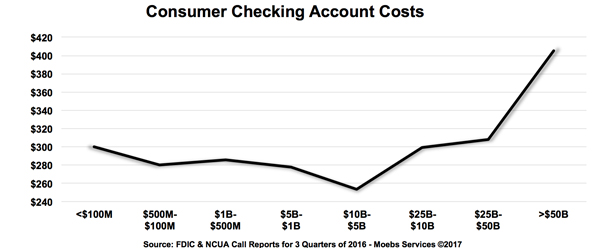

As shown in the graph below, the cost of a checking account stays somewhat consistent for institutions below $25 billion, with the exception of those between $5 billion to $10 billion in assets.

The lower average cost for a checking account with an institution in the $5 billion-$10 billion range stems from the number of efficiently run organizations within that asset size category, where nearly half operate at an efficient expense level.

Taking a look at opposite ends of the spectrum, very large institutions above $50 billion, especially the Too Big To Fail depositories, average around $400 per checking account, while those below $100 million in assets average about $300 per checking account.

Conclusion: The cost of trying to maintain a large number of branches in order to sustain market share leadership causes large institutions to have a checking cost 35% more than community banks and credit unions.

What makes up checking account costs?

Let’s dig a bit deeper. This checking cost analysis takes a Service Costing℠ approach, which considers the number of accounts as well as the transaction volume.

Many depositories still use manufacturing cost or activity-based costing approaches.

These old, non-financial service cost analyses approaches were developed to analyze aspects of the manufacturing of goods and products, not running a bank. So, in thinking it through you find they are substantially less accurate for dealing with the huge and varying volumes produced in financial services.

To put this in perspective, a bank over $1 billion in assets does more volume in transactions—even just payments items—in one day than General Motors does in a month—cars and trucks.

Overall, Service Costing℠ is defined in four basic service categories:

1. Direct Checking Costing: Administration and operation services

2. Indirect Checking Costing: Software, equipment, and related administration

3. Risk Costing: Overdraft losses, unpaid closures, fraud, and more

4. Overhead Costing: Buildings, utilities, travel, etc.

Large and efficient CUs use lowest cost to reflect lowest prices

Large credit unions stand out for their difference in average checking account cost—especially the asset category of $5 billion to $10 billion.

Star One Credit Union, based in the San Francisco area, reflects this group the best. Star One has very low checking costs. This is due to its efficient operations and is reflected in low prices with the overdraft program: $15 per overdraft, $30 de minimus balance, and up to $2,000 in overdraft limits.

What makes this credit union so efficient? Tight cost control. They have eight branches for an $8.8 billion asset institution. Their non-interest expenses to assets are about 0.70% whereas for all institutions that comes in at about 3.00%.

Star One operates at its economy of scale. Other banks, thrifts, and credit unions, which also operate at their economy of scale, provide extremely competitive pricing on their checking accounts.

Economies of scale have factors causing the average cost of providing a service to fall as the volume of the service increases. Or, using a football analogy, economy of scale is when all three teams of 11 men— offense, defense, and special team—operate the most efficiently with coaches and staff to produce ongoing winners.

Overall, having a low checking account cost allows banks, thrifts, and credit unions to have more pricing flexibility and relationships where all of their services are profitable. This is the future.

Community banks get their share

The small community bank is right there in the competitive fray and battling for its piece of the action. While too small to be at their economy of scale like the large credit unions, their cost is still only 75% of the very large banks.

Community banks don’t offer much free checking. But their price for overdrafts averages $25—and that figure hasn’t changed in seven years.

They have one huge advantage over the Too Big To Fail banks and large credit unions; as their size grows their costs fall.

They are like the little furry mammals of the Ice Age, and they still exist while all their large competitors, the dinosaurs, are gone forever.

Conclusion: Checking = Price Less Cost

Checking account transaction volume has changed significantly in the past 20 years. Today, the complexity of checking accounts allows the consumer to use their checking account in more ways and more often. Some days, a single consumer may have anywhere from two to five transactions or more, pushing payment system volumes up dramatically. This includes every transaction using the account, from debit card purchases to ACH items to, even, paper checks.

Along with transaction volume, the total number of checking account types offered by the organization also greatly affects checking efficiency. An easy way to control costs is to reduce the total number of checking accounts offered by including more features within each account.

Hopefully in the next five years, more financial institutions will be making their checking account portfolios a more efficient and profitable service to enhance the value of the household relationship.

Most important, in the not too distant future checking accounts will become a profitable service for all banks, thrifts, and credit unions.

What can you do now?

How can your financial institution get profitable checking?

• Get as close to one checking account as you can. Bank of America offers just two types of checking.

• Minimize the number of features you offer, such as “Truck Driver Checking.”

• Reduce checking fee prices to stimulate volume, especially with millenials and the middle class.

• Learn your core DDA system in detail. Find within it help to reduce cost and stimulate fee revenue.

• Find out how the most efficient checking providers do it and emulate their ways.

Semper,

Mike Moebs

(Mike will respond to questions at [email protected])

Danielle Martorano, director of research at Moebs $ervices, contributed significantly to this blog.

Learn more about webinar “Make Checking Great Again,” Feb. 28, 2017

Tagged under Bank Performance, Management, Lines of Business, Blogs, Community Banking, The Prairie Economist,

Related items

- Wall Street Looks at Big Bank Earnings, but Regional Banks Tell the Story

- JP Morgan Drops Almost 5% After Disappointing Wall Street

- Banks Compromise NetZero Goals with Livestock Financing

- OakNorth’s Pre-Tax Profits Increase by 23% While Expanding Its Offering to The US

- One in Five Oppose Fed’s Proposed Changes to Regulation II