The Otting Effect

New Comptroller Joseph Otting—a banker—discusses CRA reform, innovation, the regulator’s job, and being a “Trump regulator

- |

- Written by Steve Cocheo

All photos by David Hathcox, http://www.hathcoxphoto.com/index.html

New Comptroller Joseph Otting has already brought some new methodologies to his agency's practices and has more such in mind. He's also bringing a banker's perspective to regulation. He says he knows "the pain points."

All photos by David Hathcox, http://www.hathcoxphoto.com/index.html

New Comptroller Joseph Otting has already brought some new methodologies to his agency's practices and has more such in mind. He's also bringing a banker's perspective to regulation. He says he knows "the pain points."

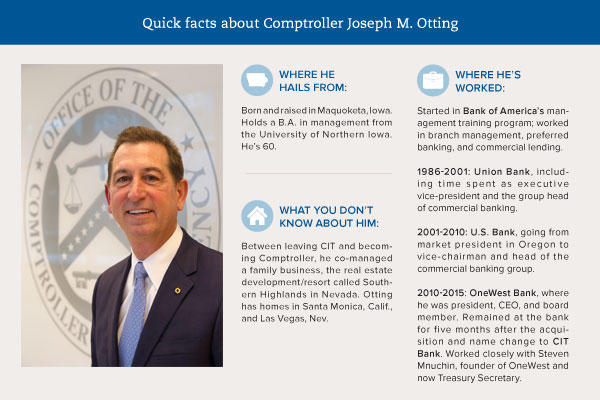

In early February, Joseph Otting, the new Comptroller of the Currency, hosted a gathering of nine former comptrollers. Only one had been a career banker prior to becoming a regulator—Otting. In fact, unlike the others, Otting isn’t a lawyer or an experienced bureaucrat. This has brought something of a new approach to OCC since Otting formally took office in late November 2017—a fresh set of eyes from a fresh background.

“There were a lot of processes here that had been built up over many, many years,” Otting explains. “People would say, ‘That’s the way we’ve always done it.’ And I’d respond, ‘Well, great, but we’re going to figure out a new way to do it.’”

Not change for change’s sake, but for the sake of functionality and efficiency. One shift is simple: that people stop showing up at meetings with thick binders stuffed with papers. Now tablets sit where paper used to.

Too many people signing off

Another shift is more meaningful: how OCC renders decisions. “There were certain things that maybe took four or five weeks to make a decision on,” says Otting. Now, “we make that decision in a day or two.”

Otting directed a rethinking of decision processes. “A lot of stuff went to the top of the house here,” he explains. That’s been replaced with a process that delegates more items down into the agency to give people the authority to approve various matters. “I want people who interact with the agency to be able to see a quicker, faster decision-making process. I want them to say, ‘Wow, this is like dealing with somebody who is in commerce.’”

Otting also shrunk the administrative cycle by trimming the number of regulators who were expected to approve a decision. “There was stuff that 20 people would sign off on that they had no ability to influence. I’d ask, ‘Why are 20 people signing this?’”

This may sound like a businessman’s disdain for bureaucrats, but Otting speaks highly of OCC staff—something one or two past comptrollers didn’t do. One goal he has for his term is to leave OCC with a solid management team with business-like attitude.

“I’ve forced back on them a lot more decisions that historically they weren’t involved in,” he says. “Issues around budgets and being accountable for your unit’s financials. That’s a new skill set that people are learning around here.”

This particular internal emphasis arises from Otting’s knowledge that bank assessments pay for OCC operations. “It disturbed me when I got here that the year-over-year budget increase was high single digits,” says Otting. He says he’s brought that rate of increase down and hopes to actually begin reducing agency costs. “We won’t do that by layoffs or hiring freezes, but by being good stewards of the monies provided to us by the institutions.”

No buffer from nitty gritty

Having been a working banker for decades, Otting says he brings a different level of understanding to his new job.

Under former Comptroller Thomas Curry, OCC had a chief of staff. Otting did not fill the position. “It’s important for me to be able to get directly involved with the people here and for them to be able to have direct involvement with me, to see the type of leader I am and the viewpoints I have. I have a voracious appetite for information and knowledge. And I like to be involved in a lot of different things.”

It is not surprising to hear that Otting typically works 12-hour days, including some weekends. He thinks the post demands that kind of schedule.

Otting also brings experience in many different aspects of banking to the table when discussing issues with his staff. “One of the beauties of coming in here with industry experience,” he says, “is that, if somebody, say, wants to talk about credit, I can talk about portfolio metrics. I can talk about individual credits. If people want to discuss compliance, BSA/AML, interest rate risk management, whatever you want, I know all of that stuff probably as good as some of the experts around here.” Much of Otting’s career was devoted to banking’s business side.

As a result, says Otting, “they don’t have to spend hours educating me on those items as they would an attorney or consultant.” He adds that because he’s been a regulated banker, he can share his knowledge of the challenges and “pain points” of handling regulatory policies.

Time to fix CRA

Early in Otting’s term, he told a small gathering of reporters that a top priority was reform of Community Reinvestment Act regulations. “We have a very complex process,” he said at the time. “The community groups don’t like what CRA is today, the banks don’t like what CRA is, and the regulators don’t like CRA.” (When the subject was broached during the recent interview, he upped the ante from “don’t like” to “hate” for each group.)

“We’re fairly far down the path on this issue,” says Otting about a CRA proposal. “We’re not talking summer; we’re still talking about the spring.”

CRA cries out for simplification, says Otting. He explains that the 1977 law and resulting regulation began very simply with the concept that banks would lend in their communities. “And over the last 40 years,” he says, “we created this highly complex animal that’s difficult to measure, communicate, and be consistent in.”

Otting says that he thinks the complexity of today’s CRA can be reduced significantly by bringing determination of compliance down to a simple metric. The base may be capital or, perhaps, total loans. The goal would be to measure CRA performance as a factor of whatever base is ultimately selected.

Part of the appeal of this approach, to Otting, is to get back to the point of CRA in the first place—“Are we getting money into those communities?”—rather than losing track of that goal amongst minutiae. He also believes this approach would provide an ongoing measure of how well a bank is meeting CRA obligations. Now, CRA exams can take some time, especially for larger institutions, and the bank’s rating may not be known for months while the exam report is being written and approved within the examining agency.

Otting says he’s been in preliminary discussions with community groups, political leaders, bankers, and OCC staff. “People kind of jump out of their chairs and give me the high five when I talk about where I’d like to take CRA,” he says. “I think we can make this simple and do more in the inner cities of America.”

Expand CRA asset classes

Otting believes a flaw of how CRA has evolved is its strong emphasis on low-to-moderate income mortgage lending and lending for low-to-moderate income multifamily housing. He thinks more types of activities should count toward meeting CRA’s intention. For example, he says, small business lending in low-to-moderate income areas should count. Likewise, he believes that building community centers that can be used in inner cities to provide job training, financial literacy, and related skills also should count. In addition, he thinks more donations that support the community should be counted; this category has narrowed substantially over the years.

Beyond this, Otting thinks student loans should qualify for CRA credit. “You’re taking a person from an underprivileged area of the community and you’re helping them reach outside that community to gain skills and be successful people,” he explains.

“I think banks will do more in those communities if we give them guidance on what will qualify, and we broaden the categories of available investments,” says Otting. Outside of cities, in suburbia and rural areas, other community-oriented lending and investments also may qualify.

“I’m open to people putting forth ideas,” says Otting. “Let’s open our minds about what can be done to improve the world. I’d like to have people talk to us about asset classes that should be included, and not look so narrowly, as has happened historically.” One suggestion that he’s heard is supporting infrastructure that brings broadband service to rural users.

Another facet of Otting’s view of how CRA regulation ought to be revamped entails a focus on results, rather than details. “If I told you to go to the Capitol and you did, and then I asked you, ‘How many steps did it take you to get there?’ You’d say, ‘I didn’t think of measuring that.’” He continues, “Let’s go right to the end and figure out the most effective way to accomplish the goal.”

Yet another change that the new Comptroller would make to CRA regulation is the concept of the assessment area. “I think assessment areas are a little archaic, frankly,” says Otting. “If banks are operating in a particular state, they should be making investments in that state. But the old days of drawing a circle around one county and saying that’s your assessment area and the only place you can make qualified CRA investments, I think that time has come to an end.”

Much of what will be proposed is anticipated to take place in the regulatory, rather than legislative, arena. The original CRA law is brief and most of what grew up around it is in the form of rules, exam procedures, and official Q&As.

Key focus: Credit quality

Former Comptroller Tom Curry brought a career of state-level bank regulatory experience to the job. Otting brings a career of being a regulated banker to it. He sees being regulated as an industry advantage, and one that he sees no banker wishing to give up. This sets the tone for his thinking on the regulator’s role.

“Our core responsibility is the safety and soundness of the banking system,” says Otting. “What does that mean? I’m a big believer that credit quality is number one, and that the only thing that can truly destroy a bank, generally, is poor credit quality. You can rebound back from a lot of things, but not deterioration beyond your capital levels.”

Even compliance and regulatory management can be seen as a facet of safety and soundness, Otting believes. And he’s established that cybersecurity will be a key focus. While historically there have been banks with reputation issues that took them down—he cites Riggs Bank’s debacle in the mid-2000s—typically credit quality is the key factor.

Is the regulator’s role in credit a leading one or a lagging one?

“It’s a little bit of both,” Otting says, “because while you are following behind an existing book of business, you are also trying to be in front of things, looking at the bank’s new underwritings.”

Look further ahead

Credit is not a static matter. “You’re constantly looking at portfolio metrics,” Otting elaborates. “What is the risk rating of the portfolio? Is it deteriorating? How is the portfolio migrating? What is the aggregate risk within the portfolio? Everything may be stable, but if three-quarters of a bank’s portfolio was highly leveraged, that would make me a little nervous about the institution.”

All this said, Otting wants his examiners to be able to get further ahead. “I want our people to be out there thinking about future risk—the risks coming down the pipeline—as opposed to what’s on the current book of business,” he explains.

To facilitate this, Otting favors more standardization of data and the way that data is delivered to OCC, “to allow us to be able to see trend lines.” He says such elements will be part of discussions at a senior OCC staff off-site meeting in April, when the leaders consider how examinations should evolve. (Otting has already indicated that a level of authority that used to be given to examiners in charge in the field will be reinstated, restoring more field-headquarters balance.)

Is there a role for artificial intelligence in compliance? Otting says he sees how AI is becoming part of AML/BSA compliance and can see why. “But it’s very difficult to audit against artificial intelligence.” Traditional rules-based systems can be adjusted, but a human is turning the knobs. With AI, the technology is constantly readjusting and recalibrating, points out Otting, and this makes third-party review more challenging.

Credit cycle and CECL

During a press meeting in January concerning OCC’s twice-a-year risk assessment, credit conditions generally received favorable comments, but bankers were warned against “complacency”—the agency’s word—multiple times.

“I think bankers are much better at risk management than we’ve really ever been,” says Otting. “They have more tools for seeing and monitoring risk. So what we’re trying to do is remind them.” So long as banks maintain current risk levels and don’t become overambitious in their underwriting, he says, “I think the industry can hold this position.” He believes the slow start of this cycle’s recovery phase, followed by steady growth, and then a bit of a “turbo charge” on the back end of the recovery, may enable favorable conditions to continue for a couple of years.

Bankers always have their eyes on the economy, but making a feel for the future more important is the coming implementation of the Financial Accounting Standards Board’s CECL—Current Expected Credit Loss model. This will require establishment of loss reserves based on long-term projections, in brief.

“There’s good analytical data available both externally and internally for people to make those estimates,” says Otting, which will have to be “life of loan” projections. A balance between conservative and liberal credit expectations will have to be balanced, notes Otting. “You can’t just use the best of times to make a prediction of what your loss will be,” he says.

Innovation and the fintech charter

During last December’s press meeting, Otting made remarks that some reporters took as a clear endorsement of the fintech charter concept developed during Comptroller Curry’s time. Banking Exchange had taken what was said differently, more along the lines of “Interesting, but let’s see a little bit more of what’s involved here.” Asked about this, Otting’s says: “I think your assessment is accurate.”

Since that press conference, Otting says he and relevant staffers have had several “deep dives” on fintech charters, and these talks continue.

The fintech charter may seem simple in concept, but Otting says there are many implications for it within and outside of OCC—both positive and negative.

Some of the questions Otting has: How do you examine and monitor a fintech given a charter to perform a particular function? How would it be funded? What would be the funding requirements?

One of the attractions of a national charter is preemption of certain state-level rules and state-level licensing. Concern over that, in part, drove lawsuits by the Conference of State Bank Supervisors and New York State’s Department of Financial Services. (The New York case was dismissed last December as not being “ripe” as the charter remains a work in progress, not a finished product. The CSBS case remains pending.)

“Everybody views preemption as the Holy Grail in that space,” says Otting. “But often they don’t understand what comes with the Holy Grail—requirements for capital, liquidity, compliance, CRA, etc.”

Otting adds that he thinks Curry did a good job starting the conversation about this new concept. “I would hope in the next 90 days,” says Otting, speaking in early February, “that I can reach a position about my support or nonsupport for a move forward with a fintech charter.”

Banks should be marketplace lenders

Having settled this question thus far, Otting makes two other points about innovation, which he says he favors.

First, he says banks are no strangers to technological innovation. It’s been going on for decades, stretching back to the introduction by banks of the first ATMs. Otting believes regulators should encourage innovation, making sure it falls within industry rules and regulations.

What if something looked appealing but fell outside the regs? “You’d have to ask yourself if it is plausible to change those rules and regulations to support that innovation,” says Otting.

“I’m a supporter of innovation,” he says. “I think innovation is what drives success.”

As a second point, Otting suggests stepping back and looking at what makes fintech hot. As an example, he points to marketplace lending to consumers. “Why are fintechs interested in that space? Because, for the most part, banks left that space, small ticket consumer lending,” he explains. “If you have a big market that’s unfulfilled, someone is going to step in and serve that market.”

Otting would like to see banks step up to fill the consumer need for small loans, again with their own fintech-style consumer credit services.

“I think there was a position previously that OCC did not really want banks to be in that space,” says Otting. “But I think banks should be in that space. I think banks will do it cheapest, safest, the most regulated, and fairest.”

On being a “Trump regulator”

Decades ago, most bank examinations tended to be consultative, not adversarial. Exams by OCC especially had a reputation for being so. Through a series of crises, the regulator-banker relationship often became more “scratchy.”

Otting thinks much of this has faded, and that relations have improved between OCC and national banks. “Cycles have a tendency to draw regulators and bankers together and then to push them further apart,” he says. His recent experience as a banker has generally been one where exams were a “value-added” experience.

In his early days at the agency, Otting has spent some time reaching out to national bank leaders. “A common theme I heard from the CEOs was: ‘It’s perhaps been a tough couple of years of working on our compliance and our BSA, but I want you to know that your people were always highly respectful and brought a tremendous amount of value when we sat down and had dialog.’”

Rougher times require tougher regulation, Otting says. He points to periods like the Great Recession. “Regulators have to stiffen their spines and step in, and often be tough with the management teams and set the expectations,” he explains. (Otting does have views on how regulators handle enforcement, based on personal experience when OneWest Bank was caught up in the robosigning controversy. This was treated within our online coverage, “A banker takes OCC’s helm.”)

Harking back to earlier comments, saving federal money is a theme heard a great deal out of Washington in the last year, from Trump appointees and the President himself. This prompts the question, is there such a thing as a “Trump regulator”?

“If there is ‘Trumpism,’ I think that it’s people who believe in America and capitalism and that people taking risks should be rewarded with success,” says Otting. “I have always been a believer in job growth, creating jobs for people. When you do that, many positive things happen to them.”

To view this cover story from the March Banking Exchange as a magazine article, click here.

Tagged under Management, Financial Trends, Compliance, Feature, Feature3,