Supersize that bank for you?

10 years on, world's biggest banks keep getting bigger

- |

- Written by S&P Global Market Intelligence

S&P Global Market Intelligence, formerly S&P Capital IQ and SNL, is the premier provider of breaking news, financial data, and expert analysis on business sectors critical to the global economy. This article originally appeared on the SNL subscriber side of S&P Global's website.

S&P Global Market Intelligence, formerly S&P Capital IQ and SNL, is the premier provider of breaking news, financial data, and expert analysis on business sectors critical to the global economy. This article originally appeared on the SNL subscriber side of S&P Global's website.

By Lindsey White and JahanZaib Mehmood, S&P Global Market Intelligence staff writers

A decade after the financial crisis, the U.S. continues to debate whether financial reforms put an end to too big to fail—the concept that banking institutions are so large and integral to the financial system that the government could not afford to let them go under.

Yet, while the world's biggest banks are much better capitalized than they were a decade ago, they are also much bigger.

Looking at megabanks

In the wake of the near-collapse of large parts of the financial system, international regulators boosted capital standards and established a list of global systemically important banks, or G-SIBs, which are subject to even more stringent regulations. The world’s largest banks have raised more than $1.5 trillion in capital, giving them high-quality buffers as much as 10x higher than a decade earlier, according to the Financial Stability Board.

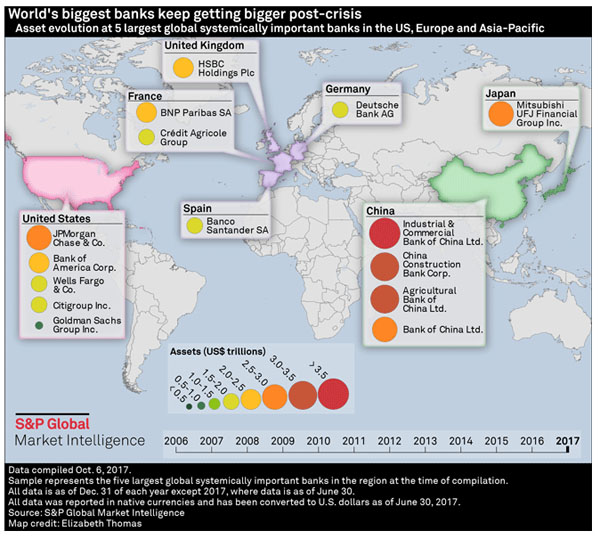

But the 30 G-SIBs are also almost all significantly bigger than they were in 2006, the year before the subprime mortgage market began to buckle.

Click on the diagram above to access a version that shows the changes from 2006 to 2017

In the U.S., New York-based JPMorgan Chase & Co. has nearly doubled in size since the end of 2006, totaling $2.56 trillion at Sept. 30. Bank of America Corp.'s asset size has increased by more than 50%, while at beleaguered Wells Fargo & Co., assets are nearing $2 trillion, more than 300% larger than pre-crisis. Much of the growth at these banks is a direct result of crisis-era mergers orchestrated in conjunction with banking regulators to help shore up the financial system. These banks' sizes are measured under GAAP and would appear even larger if measured under International Financial Reporting Standards used outside the U.S.

In Europe, London-based HSBC Holdings Plc had $2.49 trillion in assets at midyear 2017. This is up significantly from $1.86 trillion at year-end 2006. A few have shrunk, like Royal Bank of Scotland Group Plc, which grew rapidly into the world's fifth-largest bank on the eve of the crisis with $3.66 trillion in assets but is now a milder, retail-focused shadow of its former self, and majority-owned by the U.K. government.

The growth is most pronounced in Asia. China's four G-SIBs have all more than tripled their asset sizes over the last 10 years. The biggest, Industrial & Commercial Bank of China Ltd., had $3.76 trillion in assets at midyear 2017.

“TBTF” remains controversial

Too big to fail remains a subject of heated debate in the U.S., where every few years politicians propose legislation to break up big banks.

In a recent report President Donald Trump commissioned on U.S. financial reform, the Treasury Department discussed the need to eliminate regulation "that fosters the creation or cements the market position of too-big-to-fail institutions" in order to prevent taxpayer-funded bailouts.

Of course, asset size alone does not equal risk. And regulators around the world have put more stringent capital requirements in place in the wake of the crisis—G-SIBs, for instance, are subject to a capital surcharge based on five systemic risk factors: size, interconnectedness, cross-jurisdictional activity, substitutability and complexity. Regulators have also introduced stress testing and "living will" plans that make the biggest banks map out how they would wind down in the event of a failure.

International regulators also have implemented a Total Loss-Absorbing Capacity requirement to ensure big banks have enough capital and liabilities to be written down if they run into trouble. And in the EU, the European Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive aims to prevent the failure of systemically important banks with new capital standards like the Minimum Requirement for Own Funds & Eligible Liabilities.

But if and when another crisis hits, the biggest players will be far larger than they were in the last crash.

This article originally appeared on S&P Global Market Intelligence’s website on Nov. 17, 2017, under the title, "10 years on, world's biggest banks keep getting bigger"

Tagged under Management, Financial Trends, Feature, Feature3,