Still a housing crisis in rural America

Persistent and daunting challenges face country communities

- |

- Written by Melanie Scarborough

A few years ago McDowell County, W.Va., found itself in a situation not uncommon in rural communities: Its school district had dozens of vacancies, but the town lacked the sort of housing options that could draw young teachers to the area.

To remedy that, a coalition of public and private organizations raised the money to build Renaissance Village, set to open next year, which will offer affordable housing and amenities for teachers and other young professionals.

The if-you-build-it-they-will-come model is one approach to the problems of rural housing, which are as large and divergent as rural America, according to experts gathered for a forum, “The Future Of Rural Communities: Implications For Housing,” hosted in May by the Federal Reserve Board.

Rural housing problems and solutions

Eric Belsky, director of the Division of Consumer and Community Affairs, explained that the Fed is “very interested in the extent to which credit—mortgage, small business, agricultural—is flowing into rural communities because of our role as a central bank and our interest in understanding what’s going on in all the areas.”

Much of what is flowing to rural America is a steady stream of problems, according to panelists.

Peter Carey, board president for the Housing Assistance Council, says rural housing has three primary challenges: capital, capacity, and visibility. (HAC is a nonprofit corporation located in Washington, D.C., with regional offices in Atlanta, Kansas City, Albuquerque, and Sacramento.)

“We know capital is not getting to rural markets,” he says. As for capacity, there are very strong non-profit organizations in rural areas, but local governments really don’t have the ability to be of much help. And there’s the problem of visibility.

“Many people tend to look at rural America as ‘flyover country’,’” Carey says. “Decisions are made by people who have no connection to those areas. It’s hard to keep in mind something you’ve never experienced, never seen.”

Another reason rural areas don’t attract much interest from investors is persistent poverty.

Jane Graf, president and CEO of Mercy Housing, acknowledges that “one of the biggest challenges for rural housing is the economic challenge. As you look at where we can be effective and where we can afford to be, it drives you away from the rural environment. The scale is so large.”

As is the need. Mercy Housing owns a portfolio of rural properties in Washington state and Northern California that has 96% occupancy. Those families have an average income of $15,000; in senior households, it’s $12,000.

“If those resources were lost, it would be devastating for these families,” Graf says. “These units would be impossible to replace.” Understandably, she sees housing preservation as key.

Another approach is rehabilitating the existing housing stock, a goal in South Carolina, which is largely rural and poor.

“We’re trying to find money for rehab more than for new construction—construction costs are high,” says Bernie Mazyck, president and CEO of the South Carolina Association for Community Economic Development. But the inability to fund new construction means choosing from a limited menu.

“Rural residents must rehab existing housing stock or use manufactured housing, which means they have less choice,” Mazyck says.

New construction also is hindered in South Carolina by the informal way many African-Americans transferred land to descendants.

“That prevents a large number of residents from building because they don’t have clear title to their property,” Mazyck explains. Murky ownerships and a sluggish economy repel many investors, so a growing number of Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFIs) are becoming alternative lenders in the state. “We’re not seeing as much effort from conventional lenders in South Carolina to providing capital,” Mazyck says.

Low rural prices seen as plus

That may be short-sighted, given that one of the silver linings in rural housing is the advantage of its low costs.

“At least some data suggests that risk is lower too,” says Bill Emmons of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

Emmons, executive vice-president, points out that houses in some of the nation’s poorest areas, such as rural Mississippi, have had more cumulative price appreciation and less volatility than those in expensive urban areas.

“Lower housing risk can produce better long-term financial outcomes for rural families,” he says. “Suburban families have been crushed by mortgage debt, which was concentrated in urban areas.”

Crisis didn’t spare rural areas

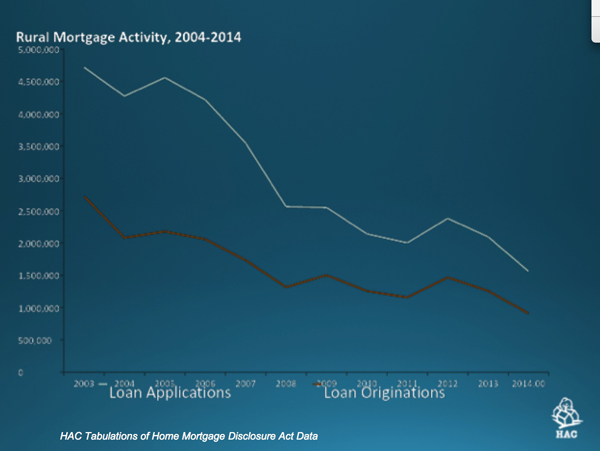

But Lance George, research and information director at the Housing Assistance Council, argues that the housing crisis hit many parts of rural America as well—and recovery there hasn’t been as robust. Three demographic segments that persistently lag, he says, are renters, many of whom pay nearly half their income for housing; Southerners; and minorities.

Lisa Mensah, Under Secretary of Rural Development for the U.S. Department of Agriculture, is particularly concerned about two other groups: millennials and farm workers. Indications are that millennials will be less wealthy than their parents, which means it is less likely they will be able to buy houses.

“We can’t talk about wealth in America without looking at home equity,” Mensah says. “So when we look at what millennials will have, we need to look at their ability to own a home.”

Perhaps no group faces greater struggles than farm workers.

“The lack of ability to house the farming workforce is huge,” Mensah says. Carey says that in many places, the only decent housing available for farm workers is publicly supported. The rest “is some of the most deplorable in this nation. It’s shameful, and it exists primarily because it’s in rural areas where there is lack of visibility and lack of voice.”

Yet Janet Topolsky, director, Community Strategies Group, the Aspen Institute, says progress often lacks visibility as well.

“There’s lots of innovation in rural housing that provides hope—it’s just not known or not connected,” she says. “There’s plenty of stuff that’s working out there.”