Viewpoint: FDIC rate caps miss the mark

Good news is, improvements can be made easily

- |

- Written by Neil Stanley, The CorePoint & TS Banking Group

When average doesn’t represent typical, and the regulations don’t allow discretion, adjustments are needed.

A regulatory burden is unnecessarily crippling some financial institutions as out-of-date processes on restrictions of deposit interest rates become increasingly out-of-step with today’s deposit pricing. Yet FDIC cannot waive the interest rate restrictions, found in Section 29 of the Federal Deposit Insurance Act.

The agency’s regulatory analysis is supposed to give those banks that are less-than-well-capitalized the ability to compete for deposits, while maintaining a fair degree of rate discipline. However, today they turn out to be far more constraining than when they were conceived.

This may not apply to your bank today, you think, because you are well-capitalized, as are many other banks. But what consequences across the industry could show up in other regulatory rules if this clearly unfair burden is not addressed promptly and equitably?

Looking at impact of the regulation

It is easily observed that FDIC-reported average rates understate today’s market for FDIC-insured deposits. Compare FDIC’s reported average for savings with any advertised savings offering and you will find a stark contrast. The mathematical average does not represent the typical opportunity for savers today.

The regulations, last visited in May 2009 and effective in 2010, say that covered institutions:

“… generally will be permitted to offer the ‘national rate’ plus 75 basis points. The ‘national rate’ will be defined, for deposits of similar size and maturity, as a simple average of rates paid by all insured depository institutions and branches for which data are available. For those cases in which the FDIC determines that the national rate as published on the FDIC’s website does not represent the prevailing rate in a particular market, as indicated by available evidence, the depository institution will be permitted to offer the prevailing rate in that market plus 75 basis points.” (Emphasis added.)

Until now the interpretation of this rule has been that the reported rates are the mathematical average for only conventional-term CD offerings at all bank branches. This approach overweights the large commercial banks, which have many branches with exactly the same offerings.

Meanwhile online-only banks with billions in retail deposits due to their aggressively priced offers impacting savers across the country contribute the same to the computation of the mathematical average as a $50 million community bank.

Looking at the market

Additionally, the typical financial institution today has expanded their CD offerings to include:

1. Standard conventional terms that are identified in FDIC’s surveys.

2. Promotional specials for non-conventional terms that are surveyed but not currently incorporated into the averages.

3. Negotiated relationship-priced offerings to preferred clients that never show up on surveys.

As banks have improved their CD sales process and rates have risen, bankers have lagged interest rate increases on standard terms. Bankers now offer a spectrum of special terms which more closely reflect market interest rates.

And many have discovered the importance of sequentially introducing customized deposit offers to depositors in a consultative sales process.

This enhanced approach is much more effective in attracting and retaining properly-priced deposits than relying exclusively on raising interest rates on conventional-term CDs to keep depositors satisfied.

Introducing the expanded set of offerings has helped banks keep the weighted average cost of funds down. But, it also means that the actual deposit market pricing is no longer reflected in averages of conventional terms that ignore the considerably higher priced non-conventional terms.

Therefore, the regulatory analysis that’s in place no longer suits. It was conceived at a time when wholesale and retail-based pricing were more closely aligned, and retail pricing was more homogenous.

Looking at some current numbers

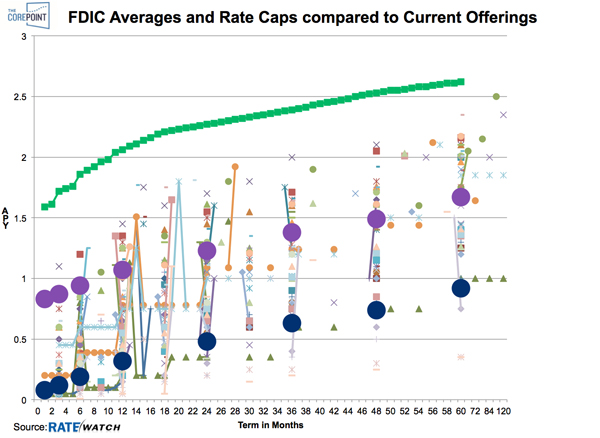

Here is a depiction of the average rates and rate caps as of Jan. 16, 2018. Also displayed here are the actual offerings within a specific financial institution footprint that could be representative of many marketplaces across the U.S. today. The green line represents FHLB advance rates. The dark blue circles are national average rates. The purple circles are rate caps.

You can see many offerings around and above the rate caps. It becomes apparent that rate caps are closer to typical rates than exceptional.

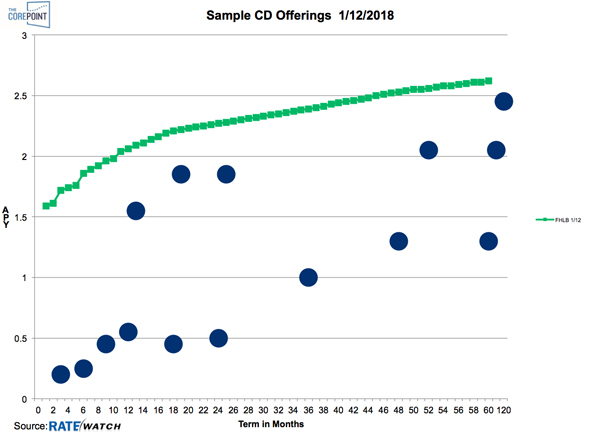

Below are the offerings of one particular financial institution, as an example. The low rates are standard terms and the higher APYs represent their off-term specials. The magnitude of pricing difference is highly significant.

How can this be fixed?

To reform the analysis in order to achieve the original intent of the rate cap approach, I suggest these improvements to the process:

1. Include special rates for any terms of less than or equal terms in the averages.

2. Include each financial institution only once—not multiple locations, which overweight large branch systems.

3. Respecting the relevance of online-only banks in local markets, allow bankers the opportunity to factor in online offers into the prevailing rate in their particular market.

4. Consider U.S. Treasury yields or wholesale funding such as FHLB advances in the determination of rate caps.

Going back to the quotation I cited earlier from the final rule, clearly, that language would allow an 11-month special to be consistently reflected in survey data of 12-month terms if the surveys were compiled by using for highest current offerings of any terms shorter than or equal to the standard term surveyed.

This would much more closely reflect the deposit pricing choices of depositors as depositors engage them today.

Addressing this issue via the surveys would mean that no regulatory changes would be required. A more inclusive interpretation would be sufficient. If an 11-month special of the bank must be consistent with the 12-month rate survey, then the 12-month rate survey should reflect existing 11-month specials.

I suggest that even if no other changes are made, the averages need to reflect prevailing rates in the market by reporting for each term the highest rates offered on any terms shorter than or equal to the standard term being averaged. This would thereby include non-conventional term specials which often dominate the new and renewed deposit activity. This could be accomplished by merely adjusting the average calculation from the existing survey data. It could be changed simply, easily, and quickly.

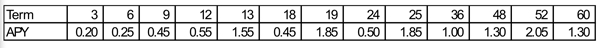

Consider a financial institution with these current offerings:

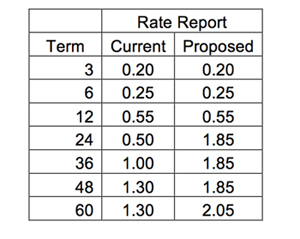

The averages would be adjusted as follows:

If this modification doesn’t achieve equitable pricing, banks should be able to build a case that the local market also includes the existence of online-only banks that are clearly gathering deposits within local markets with the dominance of their ubiquitous marketing campaigns and their 24 x7 online presence.

Beyond that, a new regulation could be pursued that alters the calculation to be done on the basis of Treasury yields or wholesale funding alternatives, such as FHLB advances. This parameter could be a spread or percentage of these yields.

Separately or together, these proposals would much more accurately reflect the offerings in the marketplace and bring the rate cap approach back to the intended relevance that was originally designed.

Getting it done

Significant progress could be achieved without rewriting the final rule simply by interpreting the average to be an average not just of a discrete term, but by considering the highest yield of all terms less than or equal to that term.

This survey approach would be consistent with the approach of depositors. They disregard lower yields in longer terms when higher yields for shorter terms are available.

Making the national rate more reflective of the actual deposit rate market could be accomplished quickly and efficiently while producing more equitable results.

About the author

Neil Stanley is founder and CEO of The CorePoint, a financial technology firm providing the CoreCD® deposit sales and pricing platform. He also serves as president of community banking at TS Banking Group, which operates in Iowa, North Dakota, and Illinois.

Tagged under Management, Financial Trends, CSuite, Community Banking,

Related items

- Wall Street Looks at Big Bank Earnings, but Regional Banks Tell the Story

- How Banks Can Unlock Their Full Potential

- JP Morgan Drops Almost 5% After Disappointing Wall Street

- Banks Compromise NetZero Goals with Livestock Financing

- OakNorth’s Pre-Tax Profits Increase by 23% While Expanding Its Offering to The US