Rethinking community banks’ future

Not panic, but resolve—and some frustration. “Now is the time”

- |

- Written by Steve Cocheo & William Streeter, Banking Exchange

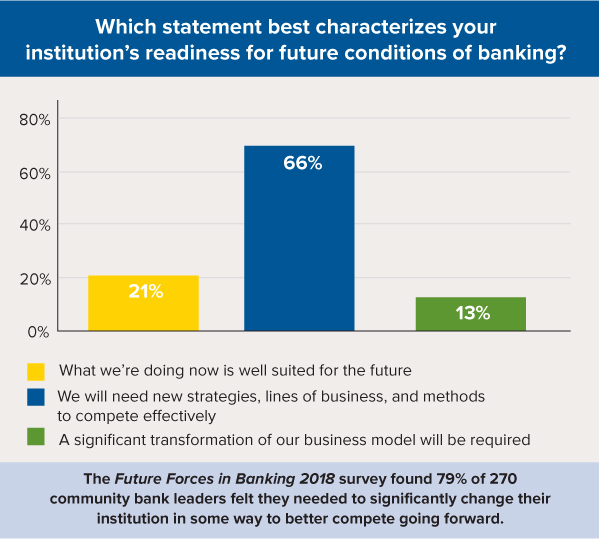

With few exceptions, the status quo won't cut it in the future, and the necessary changes range from tweaks to serious redesign. Bankers, consultants, and others weigh in on how to revamp community banking.

With few exceptions, the status quo won't cut it in the future, and the necessary changes range from tweaks to serious redesign. Bankers, consultants, and others weigh in on how to revamp community banking.

Recently, Luanne Cundiff took a call from a small business owner who asked, “Can your bank set me up for same-day ACH service?”

“I thought, ‘Wow, he knows what that means,’” says Cundiff, who is president and CEO of $374.3 million-assets First State Bank of St. Charles, Mo. “And he was not a 20-year-old customer.”

The conversation demonstrated for Cundiff yet again that customers want faster payments and faster, more convenient banking. “We’re definitely in a period of transformation,” she says.

“I’m very concerned about being able to offer them these new options,” says Cundiff. Like many community banks, First State is dependent on how quickly its primary technology provider can bring it new backshop and customer-facing technologies.

“I recently told our board that now is our time to accelerate our customer innovation,” says Cundiff.

Less talk about regulation

This is a small taste of what was learned by speaking to more than a dozen community bankers and others around the United States. The level of urgency among them varies with competition and other market factors.

“There’s not a general panic,” says Jim McAlpin, leader of the financial services practice at Bryan Cave. “I do think that there is a pervasive awareness that the industry is changing, and a growing understanding of what that change needs to be.”

Understanding, but also some frustration.

Laurie Stewart, president and CEO at $644.5 million-assets Sound Community Bank, Seattle, Wash., says community banks spend too much time talking about regulation. More talk has to be about the future.

“We need to reinvent ourselves, or we are going to be left behind,” explains Stewart. “We don’t talk about this enough. We are quick to talk about regulation, but we seem skeptical of innovation.”

Frustration, innovation, and regulation all mingle for Portland, Ore., banker Trey Maust. He feels regulators don’t necessarily want to see banks becoming more innovative. For instance, he says, a standard strategy of innovative organizations is trying new things in bite-sized chunks: You try, you learn, and you try some more.

However, Maust, executive vice-chairman at $183 million-assets Lewis & Clark Bank, says regulators don’t like banks that stand out by trying new things, the “tall blades of grass.”

“I feel like we should have a little bit of leeway,” says Maust. Some form of “sandbox” regulation would help, he says. “You could put a fence around it.” It’s a concept already in use in other countries, but so far resisted by U.S. regulators.

Unfortunately, Maust believes, “you don’t get rewarded for giving banks latitude in the regulatory agencies. They don’t like outliers.”

“No more excuses”

Much about innovation concerns technology, but attitude toward the need for change varies all over the lot. Frankly, there is a wide distance between the world that fintech gurus portray at conferences and what many community bankers experience back home.

At the other end of the spectrum from Cundiff and Stewart is a midwestern bank that Bryan Cave’s McAlpin visited for a strategic planning session last summer. The bank has been doing quite well in a little pocket, he says, but adds that “I felt like I was describing the internet to them” for the first time. To them, the exploding world of personal technology, Amazon Prime, and Google Everything almost seemed like something from another planet.

Yet talk to Joshua Siegel, a longtime investor in community banking, and you hear a stern warning: Get “smart” or you’re dead.

“Smart” as in smartphones. Siegel, chairman and CEO of StoneCastle Financial Corp. and managing partner, chairman, and CEO, StoneCastle Partners, LLC, thinks that community banks can no longer plead an inability to compete on technology.

“The herd is thinning,” he says.

Tools are available that can give community banks the speed to market, and agility enjoyed by fintechs, he says. Vendors of middleware (Q2, nCino, D3 are some) can enable a bank to match the competition without having to figure out how to make systems communicate.

Now, board members can’t sit around the table wondering what an API is, Siegel insists. Banks must add directors who understand the importance of such technologies or hire a chief technology officer who can keep the bank at parity with other players.

“If you can’t get to that level today, you are going extinct—you just are,” says Siegel. Community banks stress service. “But customer service today isn’t necessarily walking into four walls and a roof—it’s your phone,” he says.

“To the next generation,” says Siegel, a mobile phone isn’t a phone. “It’s a grocery store, a GPS, a camera, and more. And it’s a bank branch. Don’t you want to be able to interact with your customers every way you possibly can?” Siegel asks. “The fact is, the smart phone is a bank branch that the customer pays for.”

Does physical presence matter?

Inclined to agree about the importance of expanding on how mobile devices connect bankers and customers is Chris Nichols, chief strategy officer at $7 billion-assets CenterState Bank, N.A., in Florida.

“Moving forward, a physical presence will be less important,” says Nichols. “Our feeling is that a banker is more important than a physical presence, and what customers want to know is that their banker has their back. As technology expands, greater mobile functionality, the ability to better utilize data, and innovative ways to interact with your personal bankers will reduce the need to come into a branch.”

Maybe so, but few other subjects in banking engender such a wide range of viewpoints—and strategies—as banks’ physical locations.

For James Beckwith, it’s clear that today’s community bankers must be able to operate in both worlds: face-to-face personal contact and digital convenience. Nevertheless, the president and CEO at $972.8 million-assets Five Star Bank, Rocklin, Calif., near Sacramento, points out that Physical presence remains important, even though 68% of transactions are no longer face-to-face.

“We sell relationships, and you still need a place to meet with customers,” he says. “When you meet them elsewhere, people will ask, ‘Where’s your office?’ You also need a place for employees to work. We want them to be together. It works better that way.”

Indeed, two bankers we interviewed say that their institutions are adding new branches.

Patricia Husic, president and CEO of Centric Bank, a $554.8 million-assets bank based in Harrisburg, Pa., says that transaction volume in the bank’s four branches has been growing 20%-30% over the past two years. Husic plans to open a new branch in 2018 and another in 2019 as the bank continues to expand.

In Texas, $1.1 billion-assets FirstCapital Bank of Texas, N.A., Midland, is a poster child for branches. Although the bank has closed some branches and has a growing network of video-enabled interactive teller machines, it also has opened branches in two new markets and added one in Lubbock, Tex.

Many customers still want to meet with a personal banker face-to-face, says Jay Isaacs, president. “If you are going to open in new cities, you are going to have to open brick and mortar facilities,” he says. Branches demonstrate commitment to a market.

As with many aspects of community banking, however, much depends on the market or markets the bank operates in.

In rural eastern Ohio, at $227.7 million-assets First National Bank of Dennison, Chairman and CEO Blair Hillyer says traffic has fallen drastically in the bank’s five branches. This is partly due to the impact of digital and partly to an aging population base in some of his markets. He says the bank is talking about closing one branch.

Hillyer says his core provider enables the bank to meet the needs of customers who want to bank digitally.

“But one of the worries I have is that if you drive people away from the physical presence in the branch, unless you’re really tied to them somehow, the big banks’ tech and service is fine for them. And the big guys have the big marketing budgets.”

In western Maryland, First United Bank & Trust, Oakland, has been transforming the look and feel of its offices. For Carissa Rodeheaver, chairman, CEO, and president, the mission of the $1.3 billion-assets bank is to be the customers’ “trusted advisor.”

“I don’t want banking to be a transaction,” she explains. “I want it to be an experience.” The bank consolidated two branches, and is changing the others into places more suited to advisory roles.

Inside bankers’ heads

More than ever, there is no “typical” community bank, really. One common denominator, as demonstrated by many of the comments above: Bankers all realize change is upon the industry.

Indeed, when asked what community banks’ greatest competitive threat is, David Schaefer, chairman and CEO of $150 million-assets Oklahoma State Bank, answers: “Ourselves.”

“Community bankers often react to the actions of their competitors or the rules coming from the regulators or the laws coming from Congress instead of looking at their own strategic plan, their vision, and their mission,” says Schaefer. “While we must follow the law, we sometimes get bogged down in being overly compliant.”

He adds that while bankers should be mindful of their competition, they should not simply follow their competitors’ lead “because we don’t know what their management team is discussing or what their goals are. We might perceive them to be smart or really stupid, but that opinion is just based on outward appearances."

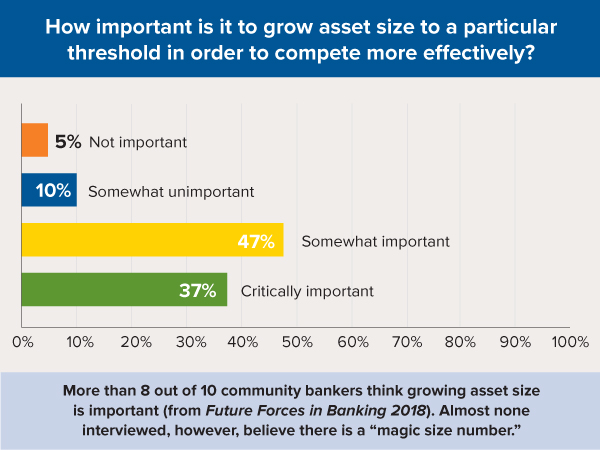

CONSOLIDATION AND GROWTH: Does asset size matter

How big should a community bank be today? Will every community bank in some way participate in the industry’s gradual consolidation?

There’s no right answer to those questions. And strategic planning notwithstanding, not every community bank will have a choice.

Regarding asset size, Patricia Husic, president and CEO of Centric Bank, a $554.8 million-assets bank based in Harrisburg, Pa., believes the more important component is ability.

“You have to deliver on your goals to earn the right to be independent,” explains Husic. Under her leadership, Centric has concentrated on organic growth, though it would consider an acquisition if the target aligned with Centric’s strategy, culture, and financial performance philosophy.

“Growth is important,” maintains Husic, “but it must be profitable growth—not just growth for the sake of growth.” She hears of community banks that buy market share via pricing and claim they will “make it up in volume.” She shakes her head, wondering just how you do that.

Consider the source

The question of reaching some “ideal” size for a community bank has currency in some circles, but others have doubts.

“My standard advice is to stop listening to the guys who are saying that your bank has to be a certain size to survive,” explains Jeff Gerrish, chairman of the board of Gerrish Smith Tuck Consultants, LLC, and a member of the Memphis, Tenn.-based law firm of Gerrish Smith Tuck, PC, Attorneys. Typically, he points out, they are dealmakers who profit by M&A.

“I don’t get that hung up by size,” says Jim McAlpin, leader of the financial services practice at Bryan Cave. “You need to be at the asset size and customer mix that allows your bank to be profitable at your particular geography.”

Independence or seeking to be acquired is not necessarily a voluntary choice. One midwestern banker interviewed has a bank that’s chugging along in a community where there isn’t much growth to be had. This banker has no family member interested in stepping in as he retires, so he found a buyer. He felt it was the best way to leave his long-time employees with decent careers.

What options are really open?

That midwestern banker was fortunate to find that avenue open. Gerrish points out that some banks have little choice but to remain independent. The smallest banks may have to remain independent because there is no compelling reason that a buyer would fancy them. “They are making enough money” to stay in business, he explains, “but no one will buy them.”

For some, selling their charter, giving new owners an opportunity to buy a going concern and move the headquarters to a more promising market, may work, but such deals hinge on many factors. Gerrish says banks not willing or able to sell need to have management succession plans in place to ensure that what they have remains viable.

Blair Hillyer, chairman and CEO of $227.7 million-assets First National Bank of Dennison, Ohio, says regulatory fatigue and leadership that is aging out are causing some bank owners to consider selling. Such frustrations get a banker thinking, and, Hillyer says, “They’re paying two times book again.”

McAlpin estimates that of the 5,000-odd banks remaining, about 2,000 have no plans to sell, and the remainder have varying degrees of willingness to sell.

However, even some banks that were grown specifically to be sold someday find buyers difficult to line up, says McAlpin. They just don’t have the niche or the market that makes them attractive, and just adding on assets may not fit the potential acquirer’s taste.

“Those banks are kind of stuck,” he says.

Seeking the magic

Others seek to build size for greater efficiency, in part because of the increasing costs of compliance.

At $150 million-assets Oklahoma State Bank, Chairman and CEO David Schaefer says that he thinks there is a minimum asset size that makes sense for community banks.

“You want to be able to serve customers with revenues over a certain size or with a loan request of a certain size,” he explains. “So you must have the capital and team depth to do so. In our case, we can do so much more than we could do just three years ago when we were $90 billion. We’d love to have the capital, funding, and team to grow to $250 million in the next three to five years. Given the costs associated with complying with regulations and our competitive markets, we have to have some greater economies of scale.”

“I feel that if we were able to get closer to $300 million, we would definitely see some economies of scale that would help,” says Hillyer. However, he adds that ‘I’ve seen many banks that merged to grow larger—to $1 billion or whatever their ideal number was—and most of them are long gone now because the merger of equals didn’t work.”

Five Star Bank, Rocklin, Calif., opened in 1999 at about $13 million in assets and is now closing in on $1 billion. President and CEO James Beckwith says he feels that is a good size. The bank’s size scales well, he believes, but the bank remains small enough to still have meaningful personal relationships with customers. Size matters, he says, but for a community bank, that personal connection is critical to success.

Ownership is a factor, too, according to Josh Rowland, CEO and vice-chairman at $212.6 million-assets Lead Bank, Kansas City, Mo. His organization is family owned, and he wants to keep it that way because he believes that local ownership matters to customers. However, he also sees the need to grow towards $1 billion in assets for efficiency and the ability to deliver services customers need. How to get there? “Everything is on the table,” says Rowland. Organic growth and acquisitions can both help build the bank.

Launching an acquisition war chest

At $1.1 billion-assets FirstCapital Bank of Texas, N.A., Midland, the bank has been dramatically growing its footprint chiefly via de novo branching, and its balance sheet via organic growth. But this will change, according to Jay Isaacs, president.

Isaacs says FirstCapital is making a strategic shift. Recognizing that there are forces pushing toward consolidation, the bank has decided to make acquisitions.

It recently raised $45 million in private equity as a war chest for making such deals. Isaacs believes that finding targets with the right cultural and geographical fit will build a larger, more efficient bank. He explains that simply crossing the $1 billion line cost the bank $200,000 more in compliance expenses. He maintains that growing the bank to $1.5 billion-$2 billion would be a good place for FirstCapital.

Read companion article, “Talent search: Is it time for new hunting grounds?”

Read companion article: “Tech is ever-widening domain for community banks”

About the authors

William Streeter is editor and publisher of Banking Exchange and BankingExchange.com. Steve Cocheo is executive editor of Banking Exchange and digital content manager of BankingExchange.com

Tagged under CSuite, Community Banking,

Related items

- Wall Street Looks at Big Bank Earnings, but Regional Banks Tell the Story

- One in Five Oppose Fed’s Proposed Changes to Regulation II

- NYCB Receives $1 Billion Lifeline

- Tackling the Affordability Challenge with a Data-Driven Approach

- Fed Must Withdraw Amendments to Regulation II, Says ABA-led Alliance