"The Alchemists" digs into central banks & crisis

Book Review: Reporter's inside view of role of key players in fire control

- |

- Written by Ed Blount

- |

- Comments: DISQUS_COMMENTS

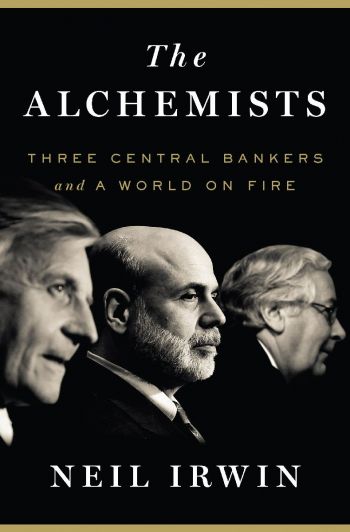

The Alchemists: Three Central Bankers And A World On Fire. By Neal Irwin. Penguin Press, 400 pp.

The Alchemists: Three Central Bankers And A World On Fire. By Neal Irwin. Penguin Press, 400 pp.

Early in 2010, when financial regulatory reform in the form of the Dodd-Frank Act was still a work in progress, Dallas Fed President Richard Fisher told a visiting congressman, "I just lent $10,000 to a bank in your district last night."

The congressman's visit had been prompted by his anger over the Fed's bailout of the Wall Street banks. And he had just endorsed Ron Paul's proposed "Audit the Fed" legislation.

"Would you have wanted to be involved in that decision?" Fisher challenged the congressman. "Because effectively, if you are going to do what you signed on to with the Ron Paul bill, you are going to be involved in that decision and making monetary policy."

Washington Post reporter and blogger Neal Irwin, who relates this anecdote in his recently released The Alchemists: Three Central Bankers and A World on Fire, reports that "the congressman was startled--he had no idea that the Fed was so deeply involved in the routine operations of local banks."

Behind-the-scenes view of crisis reactions

As the Post's beat reporter for the Federal Reserve, Irwin was near the pulse of decisions that vaulted the central bankers out of the financial trade journals and into the spotlight of popular media.

Irwin claims to have had access to the inner circles of central bankers, as suggested by his recitation of a February 2010 meeting of Chairman Fred Bernanke and his key aides to consider their options in the Dodd-Frank reform legislation. As he tells it, Governor Daniel Tarullo was pointedly excluded from the meeting. According to Irwin, Governor Tarullo was being marginalized because, "with his single-minded interest in the big banks, he had hijacked the Fed's message on Capitol Hill" and was willing to concede the smaller banks to another regulator.

Throughout The Alchemists, both American and European elected officials are portrayed as never having understood the role of unelected central banks in containing the 2008 credit crisis--much less how they may have contributed to its cause. It's an easy criticism, and one that may not be entirely unfair.

If The Alchemists gains appeal among financial executives and central bank historians--though perhaps not among policy makers--the book will do so by presenting a context for decisions made during events so fast-moving that even those at the highest levels, with the best contemporaneous intelligence, were operating with fragmentary knowledge.

History contrasted with contemporary reporting

Want more banking news and analysis?

Get banking news, insights and solutions delivered to your inbox each week.

In that way, The Alchemists is set in the style of The Lords of Finance, Liaquat Ahamed's 2009 book about the story of the central banks in the decades up to the Depression. However, unlike that well-documented history, Irwin's sources are anonymous legislative and central bank staffers, often speaking after the fact. His secondary sources are generally other journalists, also citing anonymous sources. If you're okay with that lack of substantiation, the book provides an interesting addition to any banker's library of the recent critical past.

Irwin's canny portrayals are virtual holograms of the men and women cast as lead actors in the most compelling financial drama of our time. In one example, Irwin describes a May 2011 meeting of senior officials to decide Greece's future in the Eurozone. The bankers were to meet in a secret Luxembourg location. However, just as ECB president Jean-Claude Trichet arrived, German news magazine Der Speigel suddenly revealed the meeting's existence.

"Trichet was furious," writes Irwin. "A publicly announced meeting would create expectations in the market that some major policy announcement was on the way-- and commensurate disappointment if one wasn't made." After Trichet immediately left, refusing to take part in any discussions, reporters were told that there had never been a meeting. It was a misleading, but technically accurate statement, defended by an anonymous staffer who said, in the way that bureaucrats use to justify almost anything: "We had Wall Street open at the time. There was a very good reason to deny that the meeting was taking place."

While it's well known that central bankers use communiqués or silence--at the least-- to tweak expectations among the public, Irwin tells us that similar "subtleties" are endemic among the central bankers themselves.

That summer, when the Greek meltdown threatened to spread contagion to the Italian banking system, Trichet sent a secret letter to then-Prime Minister Silvio Burlesconi outlining the reforms needed to qualify Italian bonds for the European Central Bank's quantitative easing program.

After intense negotiations, a press conference was held to outline the terms of the support program. Even among the official group, a certain level of duplicity was understood to be factored into the agreement. Despite the promises and assurances made in "private communications" among officials, Irwin quotes a senior staffer as saying, "What counted was what was said publicly. You can trust only the public commitment."

From a literary standpoint, The Alchemists presents the crisis as something of a modern Greek tragedy (pun intended), as played out within the Washington, D.C. conference room of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors and the London and Frankfurt board rooms of the Bank of England and European Central Bank. Irwin channels Euripides in showing the human faces beneath the Olympian stage (perhaps too human a portrayal for some official readers), painting senior public servants as stressed out and demanding cooperation, with expletives not deleted.

For instance, Irwin shows President Obama's then-Chief of Staff Rahm Emanuel as telling Deputy Treasury Secretary Neal Wolin to "Sit down and start ________ typing" in order to craft a financial reform bill just a few weeks before an international summit in April 2009. Later, Irwin describes staffers of the Senate Banking Committee being so appalled at the central bank's virtually unlimited power to create money that they refer to the Ron Paul bill in the most unflattering terms in relation to the Fed. (We'll leave actual quotation of their terms to the book.)

The human side, without technical details

The Alchemists is essentially a series of character studies framed against the shock of the global crisis and the fatigue of the ensuing financial reform negotiations. The book offers no charts, tables, or figures to detract from the narrative about the stresses on the central bankers. Irwin glides past these inside-baseball complexities and purports instead to expose the hot-stove politics of the three key powers: the Fed, European Central Bank, and Bank of England, with a supporting role for the International Monetary Fund.

Unfortunately, the book is not a complete record of the crisis and its aftermath. There were crucial episodes and debates that evidently failed to capture Irwin's attention.

Except for describing the congressional horse-trading over the Fed's post-crisis regulatory role, Irwin fails to describe how Dodd-Frank was a response to the events that led to the crisis or its aftermath.

For instance, no mention is made that the critically important Section 13(3) lending authority used by the Fed to save Lehman's beleaguered counterparties was later restricted in the reform legislation to an indirect liquidity facility. In any future crisis, the Fed will only be able to inject funds into a market, not directly into its participants. Clearly, a majority of elected representatives have disagreed with the Fed's actions in that regard--though the entire debate appears nowhere in the book.

Irwin also omits any mention of the Fed's 2009 stress tests, while both Chairman Bernanke and Professor Alan Blinder--former Fed vice-chairman--have cited these as the turning point in the acute phase of the crisis. Similarly, Irwin makes no mention of the alleged LIBOR rate fixing by UK banks, which brought down bankers previously regarded as Olympian figures, and which has now become the third wave in litigation threatening to engulf the global banks.

Despite these omissions, Irwin has produced a valuable contribution to the record of the forces that will help create the new world of banking and finance in the 21st Century. His conclusion is hard to dispute: "Their successors will learn from their failures. Democratic societies entrust central bankers with vast power because some things are so important yet so technically complex that we can't really put them to a vote. We're wrong to expect perfection. But we must expect progress."

Most, if not all financial crises are followed by intense emotional reactions, which foster a misunderstanding of complex causes and usually lead to a wave of new legislation, regulation, and litigation. Not to be outdone, publishers fill up shop (and online) racks with books whose authors assign culpability quickly and easily. Unlike those hot-press tabloids, Irwin's book largely avoids substantive criticism of the central bankers. That said, his depiction of Bank of England Governor Mervyn King's allegedly vacuous detachment during the early days of the crisis will no doubt rankle readers at Threadneedle Street, the Bank's headquarters. Whether true, or an example of behind-the-scenes character assassination planted with Irwin by a rival of Sir Mervyn, The Alchemists delivers a lightweight retrospective to readers who presumably have more technical analyses already in their professional bookshelves.

No doubt, The Alchemists will find its place in many libraries next to the works of other journalists, such as Too Big to Fail by The New York Times' Andrew Ross Sorkin, The Devil's Casino by Vanity Fair's Vicky Ward, and Reckless Endangerment by The New York Times' Gretchen Morgenson.

A long line of post-crisis retelling continues

For a more academic treatment, liberal-minded readers will likely turn to Princeton professor Alan Blinder's own After the Music Stopped, while conservatives will refer to Stanford professor John Taylor's First Principles.

Technocrats and apologists for the central bankers will start with Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke's own 2012 Lectures at George Washington University, then move across the pond to former U.K. Financial Services Authority chief Howard Davies' The Financial Crisis: Who is to Blame, along with former U.K. Chancellor of the Exchequer Alistair Darling's Back from the Brink.

Yet, it should be said that all these should be stacked loosely on bookshelves--as we are unlikely to have seen the last publishing venture on the crisis.

If you'd like to review books for our online book column, or have recently read a book that you found helpful that we haven't already reviewed, please e-mail [email protected]

Tagged under Books for Bankers,