The unexpurgated search for Willie Sutton

The story behind the quote that never was

- |

- Written by Steve Cocheo

- |

- Comments: DISQUS_COMMENTS

terms of money? Sutton

‘withdrew' roughly

$2 million in the course

of his career, and enjoyed

the high life when he could

live it without attracting

attention. But Sutton

maintained that nobody

could beat ‘the game.'

He spent more of his

adult life behind bars than out"

Willie Sutton was a refreshing hood. He robbed banks and he was good at it. He made no bones about that. He usually packed a gun, either a pistol or a Thompson submachine gun--"You can't rob a bank on charm and personality, so I had to carry one"-but took a professional's pride in never using it, as opposed to some of the other well known robbers of his early days. Sutton stole from the rich and he kept it, though in later years he was popular with the public through some misplaced Robin Hood idea.

Willie Sutton, a tough Irish kid born in 1901 and raised near the Brooklyn, N.Y., docks, actually didn't use the name "Willie" at all. He preferred to be called "Bill," when a life lived mostly on the lam didn't make an alias necessary. The "Willie" was bestowed on him by the police, who apparently thought it went better with the nicknames they devised for him during his career. One was "Slick Willie," a distinction he shares with other figures of recent history. The other, more common sobriquet was "Willie the Actor," and this was with good reason, as you'll see.

Sutton's criminal activity started early, with common pilferage when he was nine or ten, graduating up to breaking and entering the business of a girlfriend's father so the pair could elope.

Tempting though it might have been, Sutton never made any of the common excuses you hear from time to time about crime. His early life was spent near the kinds of sailors' dives most people today only read about and he frequented such establishments as One-Arm Quigg's Pool Hall, but he never blamed his crimes on his background or family. In fact, he worked briefly as a clerk in a Brooklyn bank long before he became a bank robber and aspired to be a bank president someday, having been weaned, so he wrote, on the get-ahead stories of Horatio Alger.

Even an early dose of incarceration didn't quell the criminality in Sutton. He said he tried, but somehow the temptation was always too much.

Learning safecracking under "Doc" Tate

Though he was to gain his fame as a bank robber, his first experience in unauthorized withdrawals from banks and jewelry stores was learned at the knee of a crook named "Doc" Tate. This Manhattan dandy was an expert safecracker who took Sutton into his gang. Tate and his crew were commuter burglars, preferring the study and burgle out-of-town banks, rather than local institutions where they'd be pursued on their home turf.

In time, Sutton went on his own with another partner, still cracking safes with all the traditional burglar tools of his day plus a few of his own invention.

Then, in the early 1930s, Sutton and his partner bungled a job because of employees who showed up early. In the course of their narrow escape some of their unique tools were left behind and this ultimately led to Sutton's first major-league stay with the state.

But that wasn't before the birth of "Willie the Actor."

Willie the Actor

Though his formal education ended with the eighth grade, Sutton was a voracious reader and demonstrated the often-rare ability to learn from experience. He rarely made the same mistake twice, with the exception of choosing partners who cheated on their women. More than once, it was a jealous female who turned on an accomplice, who invariably put the police on Sutton's trail.

But, as said, Sutton typically studied his mistakes, and was musing on the botched burglary when an idea came to him, as described in I, Willie Sutton:

"I thought about my failure when I tried to relieve the Ozone Park Bank of the contents of its vault. Doc Tate was right. The acetylene torch was not the answer. I had learned another thing about the police. Every time they caught and convicted a man, they studied his methods of operation. If I were to pull a job now, using an acetylene torch, their records would show the names of all those who had previously used that method to open a vault...

"Late that afternoon I was walking along Broadway when I saw an armored truck stop in front of a business establishment after closing hours. Two of the uniformed guards approached the door, rang the bell, and were admitted. In a few moments they marched from the store, climbed into their truck and drove off. The uniforms those guards. I doubted very much if the clerk who admitted them to the store looked at their faces. He saw the uniforms and waved them in. The right uniform was an open sesame that would unlock any door. I picked up the classified telephone directory and found several firms which manufactured all kinds of uniforms. Many of these were theatrical supply houses, and that afternoon ‘Willie the Actor' was born."

Sutton, a bit of a rake, spent some of his flusher days as a safecracker hanging out with Broadway showgirls and in the process he learned a great deal about makeup. Putting the uniforms and the makeup together with a devotion to casing a bank until he had its routine--and its weaknesses--down pat made for a mostly unbeatable combination.

Sutton's routine, with its variations, was used to take roughly 100 banks over a career spanning from the late 1920s to Sutton's final arrest in 1952-with a number of prison terms in between.

Sutton, with skin tinted, mustache added, subtracted, or adjusted, and voice moderated, would show up in the uniform or outfit best suited to getting into that bank, typically before opening time. Sutton even had a collection of hollowed-out corks used for changing the size of his nose, never resorting to plastic surgery until his last frantic days on the lam in the 1950s.

The robber would slide his way into the bank on whatever his pretext was-as a mailman, he would carry a package too large for the mail slot and ask to be let in, as a cop, he would be verifying a defective alarm system. Before the person admitting him realized it, Sutton and his accomplices would be inside. As each employee arrived, the gang would seat everyone out of plain sight and get someone to unlock the safe.

As noted, Sutton had several stays with the law, including a stint in Sing Sing, which was one of three prisons he escaped from in ingenious ways, and in Attica, which he left through another form of cleverness. (One prison, Philadelphia's Eastern State Penitentiary, now a historic site, actually makes mention of Sutton, as a celebrity, on its website.)

Indeed, when New York police arrested Sutton in 1952, he had been spotted on a subway by a young man whose hobby was amateur criminology. While Sutton belonged to no gang--he didn't trust most mobsters--the public-spirited citizen was murdered after being identified as the person who fingered Sutton. Sutton maintained to his dying day that he had nothing to do with the killing--the best guess seems to be that a gangster had his own reasons for making the hit--and though a suspect was identified the case has never been wrapped up by the New York police.

Sutton seemed to dislike violence. In fact, he claimed in his second book that he had a pistol hidden on him when he was being questioned after his last arrest. In their excitement at catching Willie Sutton, he claimed, the police had neglected to frisk him.

The final escape

Sutton's fascinating tales of life inside and outside the pen, the wife and daughter he left behind, the pain he felt he had brought to all those he loved, are beyond what this article can get into.

Was it worth it, at least in terms of money? Sutton "withdrew" roughly $2 million in the course of his career, and enjoyed the high life when he could live it without attracting attention. But Sutton maintained that nobody could beat "the game." He spent more of his adult life behind bars than out. He also helped out fellow cons on the run, and often had to maintain multiple apartments or homes so he could lay low when necessary. In any event, when he was released from prison in 1969, he had to apply for welfare for a time just to live.

That release came about as a result of a series of decisions made by the Supreme Court in the 1960s relating to legal procedures and treatment of arrested persons. Sutton, who always made a point of getting all the education he could while incarcerated, had become a sort of jailhouse lawyer through his self-education. He put together writs for fellow inmates and helped spring a few.

His own release required the assistance of a hard-as-nails woman lawyer who helped him, through a convoluted process of decisions too intricate to recount here, to overturn past decisions, chop time off past sentences, and ultimately have the final hold waived. In 1969 Willie Sutton, whose career even included a stint on the FBI's 10 most wanted list (indeed, he was the seventh person ever added to the list, when it was formalized in 1950), was a free man.

No longer living on the lam

There is surprisingly little to be found about Willie Sutton once he was released. He wasn't bad at escaping scrutiny when he was on the run from the authorities, so perhaps it's not surprising that he could lay pretty low once he (apparently) stopped robbing banks and didn't have the law on his tail. He disappeared down South.

Now and then, his name did surface. He spoke from time to time on prison reform. He consulted with some banks about anti-robbery efforts. And, in a step that amounted to sheer audacity, he made a television commercial for New Britain Bank and Trust Co., in Connecticut. The bank is buried beneath several layers of merger now, but The Encyclopedia of American Crime (Facts on File, Inc., New York) says he promoted the bank's photo credit card this way:

"Now when I say I'm Willie Sutton, people believe me."

Over the years, there was talk of making more out of Sutton's life. A Broadway musical was proposed, as was a movie version of his second book. There is no evidence to be found that either project got off the ground.

Sutton died in 1980 at the age of 79. He had been living with his sister in Florida in his last years and the family arranged for a quiet burial back in Brooklyn in the family plot. News of the demise of this erstwhile darling of the tabloids took weeks to leak out.

The final irony

So, what about THE QUOTE?

In his second book, Sutton tells, with pride, of how the medical profession adopted "Sutton's Law"--the idea of looking for the obvious, before going further afield, when diagnosing. The "law" was coined by a medical professor who recalled that Sutton, when asked by a reporter why he robbed banks, had answered with his famous line.

Except that it never happened that way. As he describes in the book:

"The irony of using a bank robber's maxim as an instrument for teaching medicine is compounded, I will now confess, by the fact that I never said it. The credit belongs to some enterprising reporter who apparently felt a need to fill out his copy. I can't even remember where I first read it. It just seemed to appear one day, and then it was everywhere.

"If anybody had asked me, I'd have probably said it. That's what almost anybody would say. ...it couldn't be more obvious?

"Or could it?

"Why did I rob banks? Because I enjoyed it. I loved it. I was more alive when I was inside a bank, robbing it, than at any other time in my life. I enjoyed everything about it so much that one or two weeks later I'd be out looking for the next job. But to me the money was the chips, that's all."

Yet, by appropriating the quote sufficiently for a title for his second book, Sutton started a chain reaction that continues to this day. This article, my search determined, is not the first time the truth of THE QUOTE was pointed out. Yet the myth persists.

Indeed, it is ironic that for the man who could bust out of high-security prisons, escape from a fiction has proven not only impossible, but is self-inflicted. The day Where the Money Was took its name, Willie Sutton was handcuffed to a lie for eternity.

And 15 years after I wrote this, the sentence continues. And so does the legend...

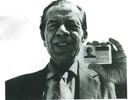

Willie Sutton was a refreshing hood. He robbed banks and he was good at it. He made no bones about that. He usually packed a gun, either a pistol or a Thompson submachine gun--"You can't rob a bank on charm and personality, so I had to carry one"--but took a professional's pride in never using it. In later years, after release from his final imprisonment, Sutton actually endorsed an early bank ID card, above. Before he turned to a life of crime (and punishment), he actually briefly worked for a bank.

As of Aug. 3, 2012, there are close to 1 million references on the web, according to Google, to Willie Sutton, the bank robber, becoming a legend for stating what some folks call an "obviosity." That is, it is claimed that when asked why he robbed banks, Sutton said, "Because that's where the money is."

Except he never said it, and is on record to that effect.

Back in 1997 this bit of banking lore became a bit of a quest for me, and after much research, I wrote about it. Conclusively, Sutton had never uttered the words. It was what today we call an urban legend, at the least. An abridged version of my search was published in the March 1997 Banking Exchange.

Since then, folks keep committing the sin of quoting Willie Sutton on this matter. As recently as 2008, the authoritative Snopes.com debunked the old legend again.

When I wrote the story, as you'll see, online search was in its infancy, snail mail still ruled, and one still read books that weighed more than a Kindle.

Periodically people see my original story online, and ask me more about it. Here is the full version of the article originally published as:

| This is the story of what became an obsession. Sometime last fall, I slit open the last of the Monday morning mail and found the text of some executive's speech. I skimmed the document for news. There it was, a few pages into the text, "it" not being news, but "THE QUOTE," which I have read and heard, even borrowed myself, hundreds of times in 18 years of writing about banks. |

"Willie Sutton rarely made the same mistake twice, with the exception of choosing partners who cheated on their women. More than once, it was a jealous female who turned on an accomplice, who invariably put the police on Sutton's trail" |

"As Willie Sutton the bank robber said, when asked why he robbed banks, ‘because that's where the money is'."

I can't say what triggered the two questions that morning, but neither would leave me alone:

1. Who the hell was Willie Sutton, anyway, and why did people keep quoting him?

2. Did this Sutton ever really say this quote-or was this just one more in the long line of myths and legends of banking that we have come to take for granted about banking and finance? There have been other famous nonevents, such as the one about stockbrokers jumping out windows en masse during the Crash (complete hogwash, by the way).

Usually, when writers on deadline can remember a quote but not who said or wrote it, they turn to the old reliable source, Bartlett's Familiar Quotations, a sort of "who-said-what" reference. Trusty Bartlett's didn't hold a clue, this time, though.

A search of the records

I had plenty of more important things to do. But that morning, and off and on since, my mind kept coming back to Sutton and his alleged quote.

At lunch I connected my computer to the Nexis/Lexis research database and searched the system for a clue.

What I found was impressive, if one considers that a bank robber is a fairly heavy-duty criminal. This robber's words, if they were his, had been borrowed by all sorts of people to illustrate all sorts of points. There were hundreds of references made to THE QUOTE just in 1996 and that was just in the publications and speeches contained in the research service's database. Further back, there were more:

Back in the early 1980s, Walter Wriston, formerly of Citicorp, used to enjoy quoting Sutton in speeches calling for financial modernization. Once, he pointed out that Sutton couldn't regard banks, who Wriston said were falling behind the times, as the only place to get money. Sutton, Wriston said, would "have to case a dazzling variety of institutions to ply his trade." Wriston used to give out booklets of pictures of figures from history and literature that included a shot of Sutton--with advice on where the money had moved.

(I had actually attended one such speech in my first year or two in the business. I had long forgotten that this was where I first heard THE QUOTE.)

The Buffalo News, writing about Senate Banking Committee Chairman Alfonse D'Amato's abilities as a "survivor," wrote, "D'Amato became the Senate Banking Committee chairman, right where, as Willie Sutton once put it, ‘the money is'."

In banking magazines, including Banking Exchange, THE QUOTE has been used to justify new product expansions and more. One case: "What was it that Willie Sutton said--he robbed banks because that's where the money was. Why am I selling retirement products? That's what the consumer wants." Another, quoting a noted regulator of the time: "People still believe that Willie Sutton was right, banks are ‘where the money is.' But it's not so clear that Willie would be as right now as he once was."

A trade association executive, writing to one of our competitors, complained that banks were being tapped to help pay for the 1996 thrift cleanup, "because, as Willie Sutton said when asked why he robbed banks, ‘that's where the money is'."

Indeed, THE QUOTE has been used in articles and speeches about bond issues, religious matters, the O.J. Simpson criminal case, Medicaid fraud, alcohol on campus, mutual-fund investment strategies, automobile marketing, and even, in a surprisingly small number of cases, bank robberies.

But who was Sutton, to be quoted so authoritatively? I mean, his one alleged quote has been printed more often in publications about banking and finance than any one thing said by any other authority, with the possible exception of the original Adam Smith.

And was the quote genuine or one of those "facts" that get picked up first by one writer, then another, until everyone who comes across that fact assumes it must be true, reasoning that if it weren't, by now somebody would have found out and remedied the situation? [Editor's Note: And the syndrome is even worse today, thanks to the internet.]

The quest continued over the next couple of months, taking me from databases to sites on the World Wide Web to the files of the Federal Bureau of Investigation to bankers association records to ... you get the idea. It came to be a bit of a fever. At one point I found myself investigating rumors of a restaurant in New Jersey that had been opened in a former bank that Sutton had robbed, that was trading on that fame.

In the end, high-tech and personal legwork notwithstanding, the most authoritative and complete information I could obtain I found through the local library.

And the source of all this library information?

A man who maintained with pride that he had never ratted out a fellow robber or fellow prisoner in his long career of crime and punishment: Willie Sutton himself.

When apprehended for the last time, in 1952, Sutton wrote, in cooperation with a well-known newspaperman of the day, a streamlined tale of his life of crime called I, Willie Sutton (reprinted in 1993 by Da Capo Press, New York). He claimed, and the claim seems genuine, that he wanted to warn kids against the lure of easy money. In fact, the proceeds of the book went to a foundation that worked with troubled youth.

Years later, after his final "escape," Sutton found another ghostwriter. Together, they came up with the ultimate Sutton saga, Where the Money Was: The Memoirs of a Bank Robber (Viking Press, New York, 1976). Sutton's story was committed to film at least once on the ancient tv series Gangbusters. [Editor's note: Subsequently, a documentary film was made.]

Meet Willie Sutton

| "Was it worth it, at least in terms of money? Sutton ‘withdrew' roughly $2 million in the course of his career, and enjoyed the high life when he could live it without attracting attention. But Sutton maintained that nobody could beat ‘the game.' He spent more of his adult life behind bars than out" |

||

Willie Sutton was a refreshing hood. He robbed banks and he was good at it. He made no bones about that. He usually packed a gun, either a pistol or a Thompson submachine gun--"You can't rob a bank on charm and personality, so I had to carry one"-but took a professional's pride in never using it, as opposed to some of the other well known robbers of his early days. Sutton stole from the rich and he kept it, though in later years he was popular with the public through some misplaced Robin Hood idea.

Willie Sutton, a tough Irish kid born in 1901 and raised near the Brooklyn, N.Y., docks, actually didn't use the name "Willie" at all. He preferred to be called "Bill," when a life lived mostly on the lam didn't make an alias necessary. The "Willie" was bestowed on him by the police, who apparently thought it went better with the nicknames they devised for him during his career. One was "Slick Willie," a distinction he shares with other figures of recent history. The other, more common sobriquet was "Willie the Actor," and this was with good reason, as you'll see.

Sutton's criminal activity started early, with common pilferage when he was nine or ten, graduating up to breaking and entering the business of a girlfriend's father so the pair could elope.

Tempting though it might have been, Sutton never made any of the common excuses you hear from time to time about crime. His early life was spent near the kinds of sailors' dives most people today only read about and he frequented such establishments as One-Arm Quigg's Pool Hall, but he never blamed his crimes on his background or family. In fact, he worked briefly as a clerk in a Brooklyn bank long before he became a bank robber and aspired to be a bank president someday, having been weaned, so he wrote, on the get-ahead stories of Horatio Alger.

Even an early dose of incarceration didn't quell the criminality in Sutton. He said he tried, but somehow the temptation was always too much.

Learning safecracking under "Doc" Tate

Though he was to gain his fame as a bank robber, his first experience in unauthorized withdrawals from banks and jewelry stores was learned at the knee of a crook named "Doc" Tate. This Manhattan dandy was an expert safecracker who took Sutton into his gang. Tate and his crew were commuter burglars, preferring the study and burgle out-of-town banks, rather than local institutions where they'd be pursued on their home turf.

In time, Sutton went on his own with another partner, still cracking safes with all the traditional burglar tools of his day plus a few of his own invention.

Then, in the early 1930s, Sutton and his partner bungled a job because of employees who showed up early. In the course of their narrow escape some of their unique tools were left behind and this ultimately led to Sutton's first major-league stay with the state.

But that wasn't before the birth of "Willie the Actor."

Willie the Actor

Though his formal education ended with the eighth grade, Sutton was a voracious reader and demonstrated the often-rare ability to learn from experience. He rarely made the same mistake twice, with the exception of choosing partners who cheated on their women. More than once, it was a jealous female who turned on an accomplice, who invariably put the police on Sutton's trail.

But, as said, Sutton typically studied his mistakes, and was musing on the botched burglary when an idea came to him, as described in I, Willie Sutton:

"I thought about my failure when I tried to relieve the Ozone Park Bank of the contents of its vault. Doc Tate was right. The acetylene torch was not the answer. I had learned another thing about the police. Every time they caught and convicted a man, they studied his methods of operation. If I were to pull a job now, using an acetylene torch, their records would show the names of all those who had previously used that method to open a vault...

"Late that afternoon I was walking along Broadway when I saw an armored truck stop in front of a business establishment after closing hours. Two of the uniformed guards approached the door, rang the bell, and were admitted. In a few moments they marched from the store, climbed into their truck and drove off. The uniforms those guards. I doubted very much if the clerk who admitted them to the store looked at their faces. He saw the uniforms and waved them in. The right uniform was an open sesame that would unlock any door. I picked up the classified telephone directory and found several firms which manufactured all kinds of uniforms. Many of these were theatrical supply houses, and that afternoon ‘Willie the Actor' was born."

Sutton, a bit of a rake, spent some of his flusher days as a safecracker hanging out with Broadway showgirls and in the process he learned a great deal about makeup. Putting the uniforms and the makeup together with a devotion to casing a bank until he had its routine--and its weaknesses--down pat made for a mostly unbeatable combination.

Sutton's routine, with its variations, was used to take roughly 100 banks over a career spanning from the late 1920s to Sutton's final arrest in 1952-with a number of prison terms in between.

Sutton, with skin tinted, mustache added, subtracted, or adjusted, and voice moderated, would show up in the uniform or outfit best suited to getting into that bank, typically before opening time. Sutton even had a collection of hollowed-out corks used for changing the size of his nose, never resorting to plastic surgery until his last frantic days on the lam in the 1950s.

The robber would slide his way into the bank on whatever his pretext was-as a mailman, he would carry a package too large for the mail slot and ask to be let in, as a cop, he would be verifying a defective alarm system. Before the person admitting him realized it, Sutton and his accomplices would be inside. As each employee arrived, the gang would seat everyone out of plain sight and get someone to unlock the safe.

As noted, Sutton had several stays with the law, including a stint in Sing Sing, which was one of three prisons he escaped from in ingenious ways, and in Attica, which he left through another form of cleverness. (One prison, Philadelphia's Eastern State Penitentiary, now a historic site, actually makes mention of Sutton, as a celebrity, on its website.)

Indeed, when New York police arrested Sutton in 1952, he had been spotted on a subway by a young man whose hobby was amateur criminology. While Sutton belonged to no gang--he didn't trust most mobsters--the public-spirited citizen was murdered after being identified as the person who fingered Sutton. Sutton maintained to his dying day that he had nothing to do with the killing--the best guess seems to be that a gangster had his own reasons for making the hit--and though a suspect was identified the case has never been wrapped up by the New York police.

Sutton seemed to dislike violence. In fact, he claimed in his second book that he had a pistol hidden on him when he was being questioned after his last arrest. In their excitement at catching Willie Sutton, he claimed, the police had neglected to frisk him.

The final escape

Sutton's fascinating tales of life inside and outside the pen, the wife and daughter he left behind, the pain he felt he had brought to all those he loved, are beyond what this article can get into.

Was it worth it, at least in terms of money? Sutton "withdrew" roughly $2 million in the course of his career, and enjoyed the high life when he could live it without attracting attention. But Sutton maintained that nobody could beat "the game." He spent more of his adult life behind bars than out. He also helped out fellow cons on the run, and often had to maintain multiple apartments or homes so he could lay low when necessary. In any event, when he was released from prison in 1969, he had to apply for welfare for a time just to live.

That release came about as a result of a series of decisions made by the Supreme Court in the 1960s relating to legal procedures and treatment of arrested persons. Sutton, who always made a point of getting all the education he could while incarcerated, had become a sort of jailhouse lawyer through his self-education. He put together writs for fellow inmates and helped spring a few.

His own release required the assistance of a hard-as-nails woman lawyer who helped him, through a convoluted process of decisions too intricate to recount here, to overturn past decisions, chop time off past sentences, and ultimately have the final hold waived. In 1969 Willie Sutton, whose career even included a stint on the FBI's 10 most wanted list (indeed, he was the seventh person ever added to the list, when it was formalized in 1950), was a free man.

No longer living on the lam

There is surprisingly little to be found about Willie Sutton once he was released. He wasn't bad at escaping scrutiny when he was on the run from the authorities, so perhaps it's not surprising that he could lay pretty low once he (apparently) stopped robbing banks and didn't have the law on his tail. He disappeared down South.

Now and then, his name did surface. He spoke from time to time on prison reform. He consulted with some banks about anti-robbery efforts. And, in a step that amounted to sheer audacity, he made a television commercial for New Britain Bank and Trust Co., in Connecticut. The bank is buried beneath several layers of merger now, but The Encyclopedia of American Crime (Facts on File, Inc., New York) says he promoted the bank's photo credit card this way:

"Now when I say I'm Willie Sutton, people believe me."

Over the years, there was talk of making more out of Sutton's life. A Broadway musical was proposed, as was a movie version of his second book. There is no evidence to be found that either project got off the ground.

Sutton died in 1980 at the age of 79. He had been living with his sister in Florida in his last years and the family arranged for a quiet burial back in Brooklyn in the family plot. News of the demise of this erstwhile darling of the tabloids took weeks to leak out.

The final irony

So, what about THE QUOTE?

In his second book, Sutton tells, with pride, of how the medical profession adopted "Sutton's Law"--the idea of looking for the obvious, before going further afield, when diagnosing. The "law" was coined by a medical professor who recalled that Sutton, when asked by a reporter why he robbed banks, had answered with his famous line.

Except that it never happened that way. As he describes in the book:

"The irony of using a bank robber's maxim as an instrument for teaching medicine is compounded, I will now confess, by the fact that I never said it. The credit belongs to some enterprising reporter who apparently felt a need to fill out his copy. I can't even remember where I first read it. It just seemed to appear one day, and then it was everywhere.

"If anybody had asked me, I'd have probably said it. That's what almost anybody would say. ...it couldn't be more obvious?

"Or could it?

"Why did I rob banks? Because I enjoyed it. I loved it. I was more alive when I was inside a bank, robbing it, than at any other time in my life. I enjoyed everything about it so much that one or two weeks later I'd be out looking for the next job. But to me the money was the chips, that's all."

Yet, by appropriating the quote sufficiently for a title for his second book, Sutton started a chain reaction that continues to this day. This article, my search determined, is not the first time the truth of THE QUOTE was pointed out. Yet the myth persists.

Indeed, it is ironic that for the man who could bust out of high-security prisons, escape from a fiction has proven not only impossible, but is self-inflicted. The day Where the Money Was took its name, Willie Sutton was handcuffed to a lie for eternity.

And 15 years after I wrote this, the sentence continues. And so does the legend...

Tagged under Blogs, Reporters Notebook,