“Sorry, but your apology is ruining our relationship”

Part 2: Get “sorry” right, or it’s just a sorry excuse

- |

- Written by Martie Woods

Last week Martie Woods began this series on the value of apologizing to customers with, “I’m happy to say I’m sorry.”

Last winter, my husband and I were preparing for a trip to Paris. Having taken several other trips out of the country, we finally got smart and decided to inform our bank that we were leaving the country and would indeed be using our debit and credit cards on our trip.

Feeling some self-satisfaction in response to having thought of informing our bank, I decided to go all out and drive to the branch.

Something about seeing the whites of someone’s eyes, right?

I had a nice discussion with the teller, and she put a note on our accounts—checking, credit, even double-checked the dates of our trip.

I was certain—this time—we would not spend 45 minutes on the phone with the fraud department, who I am now convinced tries every tactic possible to convince us that we are not actually who we say we are.

Sacrebleu! Forget Paris!

Day 3 in Paris we, yet again, find ourselves on the phone with the bank.

We are on the Champs-Elysees standing outside a McDonalds in January—not how we wanted to spend our time. (We have plenty of them back home, after all.)

After over an hour of trying to convince the fraud department that we are indeed who we say we are, we are finally back up and running.

Upon our return to the States, I decided to drive back to the branch to understand what went wrong. Turns out that in spite of saying “we” and “my husband and I” and in spite of the fact that all of our accounts are joint, the bank did not understand that my husband was going to Paris with me.

It never once occurred to me that I should have to specify all of the details associated with this one request.

Why should I? I am the customer!

At what point is the teller responsible for asking some simple questions to make sure all critical information has been acquired to satisfactorily accomplish this request?

Whether or not this should have happened is a different question and how this experience affects my overall perception of my bank is about the broader subject of problem-resolution. With this situation, at a minimum, I am pretty sure I deserved an apology I never received.

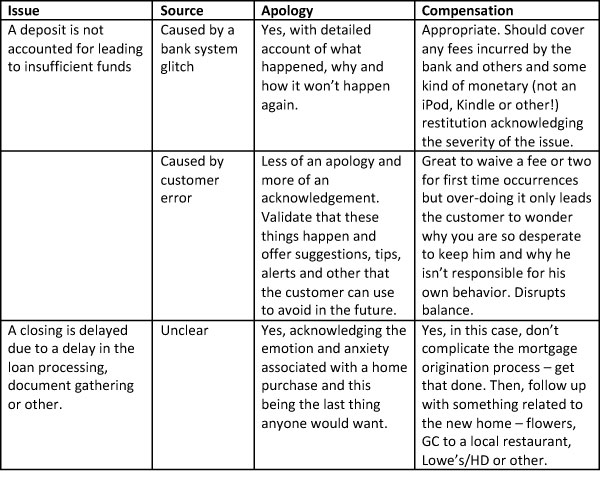

Whether or not to apologize is only the first of three tricky questions for banks to tackle in the frequently-faced “dissatisfied customer” situation.

If the bank decides to apologize, how do they do it: Accept blame and responsibility? Or simply acknowledge frustration?

And what about compensation of some sort? When is it right to compensate or give a reconciliation gift of some sort?

Fragile balance

The most important basis of the relationship is balance.

If the bank is going to be an important partner to its customers, they must maintain a state of balance that positions them as peers, partners who complement and benefit each other.

The biggest violation to this is the apology.

The industry has finally realized that apologies are appropriate, but we haven’t yet grasped how to shape and deliver them.

First, how severe is the issue?

Not by your terms, but by the customers: Significant and irreplaceable? Long-term but recoverable? Inconvenient?

The second and third scenarios are most likely and both situations benefit from an associate who first and foremost is real, human, and mentally present.

No bank-talk, no talking down.

Getting the apology right

From there, think in terms of three elements:

1. Operational: The apology needs to be complemented by action.

What processes, procedures will be adopted? What action taken? What systems and information do associates need access to in order to deliver on the apology? How can they be more timely, speedier, and more flexible?

Customers who are served by empowered employees take comfort in knowing they are trustworthy. Too many institutions convey lack of trust in their associates but expect the customer to feel comfortable letting them handle their money.

It makes no sense.

2. Interactional: This is the handling process—courtesy, politeness, urgency, empathy and respect.

Drop the formal language and speak “normally,” like one might to an acquaintance. The alternative, institutional language, creates distance and hierarchy between the customer and the associate.

3. Compensatory: Perceived fairness of the outcome of the service encounter.

This last element—compensatory considerations—is what we most often get wrong. Some situations deserve compensation of some sort, others do not.

Failing to compensate when something is expected leaves the customer feeling disregarded.

Compensating when not necessary can feel like a brush-off.

And overcompensating with something too generous can elicit feelings of guilt in the customer (really).

Each of these disrupts the balance of the relationship— the first step in leading a customer to question the overall value of the partnership and services provided. The other mistake I often see is compensating or gifting something unrelated to the issue or the context of the relationship.

You get the point.

Problems and problem-solving are less of a …. well, problem than you might think.

If we saw it more as part of the job and part of the natural relationship between customer and bank, we would be better at it and our customers would take comfort in that.

Problems act as the connective tissue between an institution and its customers.

How you handle a problem is the gauge that tells the customer the true value of their relationship with you.

Without problems, there is no depth to a relationship and in fact, a customer’s loyalty remains untested.

Beginning the improvement

Where to start? Here are some suggestions:

1. Take good, no great, care of your employees.

The experience starts and ends with them.

2. Get comfortable with relational language.

Burn your scripts. Outlines are sufficient and allow for personality. Remember what I wrote in Part 1 about humor.

3. Convey empathy.

You are a consumer too—drop your banker front.

4. Apologize sincerely.

Even if you are not accepting blame you can acknowledge stress and inconvenience.

5. Compensate skillfully.

Determine if compensation is even necessary. If so, select something that aligns to the severity of the issue. And, stay within the context of the relationship.

In closing, I leave you with the wise words of Mark Twain:

“If you commit a fault, admit it. It will throw off those in charge and allow you to commit more.”

Tagged under Retail Banking, Compliance, Customers, Compliance Management, Feature,