San Diego’s bank of niches

Like the sound of 19% ROE? Seacoast Commerce earns that with SBA lending and specialized deposit strategies

- |

- Written by Bill Streeter

How does Seacoast compete with the big guys? Speed. Average SBA loan turnaround: 30 days, with some done in just ten.

How does Seacoast compete with the big guys? Speed. Average SBA loan turnaround: 30 days, with some done in just ten.

You could call Seacoast Commerce Bank the “non-relationship community bank,” but you would only be half right. The non-relationship part applies just to lending. The San Diego-based bank is a transactional lender, but it funds those loans largely from a pair of deposit niches that are highly relationship based.

Needless to say, Seacoast Commerce is not a typical community bank—although it once was—and its CEO believes that the traditional model still works . . . in the right place.

Over the last seven years, Seacoast Commerce has transformed itself from an unprofitable bank with limited prospects into the number ten Small Business Administration lender in the country, returning 18.94% on capital (third quarter). Even among SBA lenders, the $520 million-assets bank is a specialist—it does 7(a) loans almost exclusively, not 504 loans.

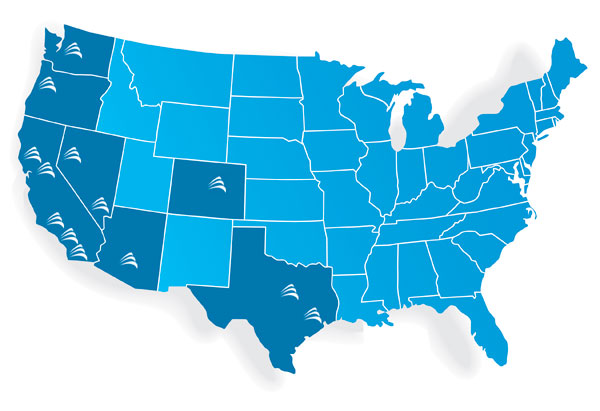

Can the bank’s model be replicated? The basic strategy can. About 3,000 banks do SBA lending, says Seacoast Commerce CEO Richard “Rick” Sanborn, but the majority have one lender who handles the business. That person typically generates about $10 million a year in loan volume. Seacoast Commerce’s SBA lenders average between $12 million and $13 million, but the bank’s formula for SBA success is straightforward: It focuses on this business almost exclusively, and it sets up experienced SBA lenders in different cities or counties—loan production offices, in other words. Currently, it has LPOs in seven western and southwestern states.

Seacoast Commerce Bank is the country's #10 SBA lender. No longer an unprofitable bank with limited prospects, Seacoast now focuses on 7(a) loans almost exclusively, with expert lenders in seven states.

Why “classic” didn’t work

Seacoast Commerce began life in 2003 in Chula Vista, Calif., as a traditional community bank serving the greater San Diego market. In its attempt to be all things to all people, the bank found it could not generate adequate returns competing against the big banks, other community banks, and credit unions. It made a wide variety of business loans—construction, multi-family, C&I, etc.—many of which began to degrade in 2007.

The bank’s owners hired Sanborn as CEO in 2007, the third CEO in four years. He had turnaround experience, had worked at other community banks wearing various hats, and had big-bank sales experience as well, including three and a half years at Wells Fargo.

Sanborn and two other investors took ownership positions in the struggling bank. When he arrived, the bank had just $63 million in assets and $11 million in capital. The initial idea was to use the charter as a “roll up”—do a few acquisitions and then sell. That changed as the bank charged off $3.5 million in the first quarter Sanborn was there ($9 million over the next two years). A quick capital raise in 2008—predominantly among directors, management, and friends—raised $4 million, and by mid-2009, they had stabilized the problems. But they knew the model had to change.

While still viable in many smaller markets, traditional community banking, in Sanborn’s view, doesn’t work in large markets—at least not in San Diego. The combination of big bank and credit union competition and Dodd-Frank regulatory costs and restrictions makes traditional pricing and margin levels unsustainable.

“In a big market,” says Sanborn, “you need to offer a full suite of consumer products and business products. However, the consumer market today is so commoditized, it’s difficult for community banks to compete in auto, home equity, and mortgage lending.”

Compounding the problem, competition for business loans in large cities also is problematic, Sanborn says. Every day, he sees ads from big banks, community banks, regionals, and credit unions offering 10-, 15-, and 20-year fixed-rate mini perm loans at 4% or sub 4% rates.

“We don’t see how that’s sustainable as a business model,” he says, “especially when rates are going to go up.” In urban markets, he believes, community banks need some kind of specialization to survive and thrive long term.

Sanborn, a recent past chairman of the California Bankers Association, does believe that traditional banks in smaller communities—where the bank “is really engrained within their community”—still works. Although even there, he notes, most banks tend to find some niche.

Given all that, Seacoast Commerce’s management team decided that they needed to change direction. Easier said than done.

“With an institution that has limited capital, there are very few products you can offer where you can make good money without growth,” says Sanborn. “The SBA program is one of them.” He explains: “When you do an SBA loan, you sell the [guaranteed portion] so you’re not growing as quickly as you would with a traditional loan, and you’re generating a pretty healthy fee, which is what we needed to fix problems.”

Enter the rainmaker

Earlier in his career, Sanborn had met David Bartram, who ran the SBA program at another San Diego institution, Bank of Commerce. Bartram went on to become president of U.S. Bank’s SBA division after the large bank acquired Bank of Commerce. Sanborn convinced Bartram to join Seacoast Commerce to help build its program.

The timing was fortuitous. As Sanborn recounts: “The marketplace was in complete disarray in 2009 as banks were going under and others were getting out of lending.” Seacoast Commerce was able to cherry pick the best SBA producers, many of whom had worked for Bartram at one time or another.

With the veteran Bartram aboard, the bank set up its new SBA unit in three months and booked its first SBA loan in October 2009, doing $11 million by year-end.

In 2010, says Sanborn, Seacoast did $94 million in SBA loans, adding two more salespeople to the initial group of four. A big boost that year was passage of the Jumpstart Our Business Startups Act, which bumped up the SBA loan guarantee from 75% to 90%.

Seacoast Commerce generated $9 million in pre-tax gain on sales revenue, taking it from a net loss of $5 million in 2009 and total assets of around $100 million, to a profit of $300,000 in 2010 with total assets just under $150 million.

Management’s goal was to get to $250 million a year in production. The current tally is 16 salespeople (“business development officers”) and production is on track to break $200 million this year, according to Sanborn.

At present, the bank has 12 LPOs in seven states: Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, Oregon, Texas, and Washington. Sanborn says they only hire people with a proven track record—“good producers who may be frustrated, or may be in an environment where the ‘credit box’ doesn’t fit for what they do.” The bank hires one to two business development officers a year.

Core plus a “kicker”

By 2012, problem loans were no longer an issue and Seacoast Commerce had “tons of capital” and great liquidity, says Sanborn. So management decided to move away from the gain-on-sale model and begin to retain the guaranteed portion of SBA loans they originated.

“There’s a lot of money to be made in [gain on sale],” Sanborn says, “but it’s ‘one and done.’” Plus, there’s a risk element. He explains: “If you sell 100% of your production, what happens if premiums go down? We would potentially lose money and have to stop production or lay people off. We don’t want that.

“The real value for our shareholders is building an institution that can produce consistent, predictable recurring income. That only comes from spread income.”

Here’s the math to back that up, per Sanborn: At current premium rates, when Seacoast Commerce sells an SBA loan, it earns an approximate 10% premium on the guaranteed portion, pretax, day one. If instead it holds the loan on its balance sheet, at the bank’s average loan yield of 5.5%, minus 50 basis points cost of funds, it has a net spread of 5%. It’s actually a little less than that, Sanborn says, but for the sake of example, at a 5% margin, the bank’s return in two years will equal the 10% gain if it had sold the loan. Sanborn says SBA loans typically run six-to-eight years, so over the life of the loan, “I’m making three to four times as much money.”

The decision was made to build up the loan portfolio for three years, selling only enough loans to break even. Following that plan, the bank’s balance sheet grew from $80 million in 2012 to $520 million currently.

Here’s the really neat thing: The spread produces the core earnings, but for the last six quarters the bank has begun selling about half its production again. The gain on sale is an earnings kicker, says Sanborn, and takes the bank’s ROE up to nearly 19%.

“You keep the relationship”

“We lend all over the western U.S., but we don’t bank any of our borrowers,” says Sanborn. “We’re not a traditional relationship bank,” he adds, referring to borrower deposit account relationships.

If Seacoast Commerce isn’t relationship driven, then it must be a rate lender, right? Actually, no.

“Our sales people know that if Wells Fargo, Chase, or U.S. Bank is in the deal, don’t pursue it because we are not going to compete with them,” says Sanborn. “The big banks do fixed-rate financing, and the only thing their salespeople focus on is rate,” he says. “We don’t do fixed-rate funding.”

So how do they compete with the big guys? Speed.

Let’s say a small business customer wants to buy a commercial building, but prefers to do it as an SBA loan because of the low 10% down payment. If the customer goes to a large bank, says Sanborn, it will probably take somewhere between 60 and 90 days to close the loan.

“Our average turn, from start to finish, is 30 days. We’ve done deals in as few as ten,” Sanborn states.

His biggest competitors are banks between $200 million and $2 billion.

In actuality, Seacoast Commerce receives referrals from money-center banks. Explains Sanborn: “Say you’re a commercial lender or relationship manager at a money-center bank and your client is trying to buy a building and do an SBA loan. You’ve signed a 60-day escrow and you’re 45 days in but don’t have a commitment letter. We get a phone call: ‘Can you do this deal in the next two weeks?’”

They call, says Sanborn, because “they know we just do the SBA loan. We don’t take the relationship. So now the money-center banker has saved his relationship, and we’ve provided the loan.”

Where relationships do matter

Bankers may be wondering about Seacoast Commerce’s cost of funds, especially because the bank has no significant retail presence. According to Sanborn, currently about 37% of the bank’s core deposits are noninterest demand deposits. Much of the rest are money market deposit accounts.

Because Seacoast Commerce is a niche lender, it sought to find comparable deposit niches where the relationship is not based on credit.

The most significant is the homeowner association and property management industry. HOAs typically don’t have borrowing needs, explains Sanborn, just deposit needs.

“Our typical property management client manages 50 associations,” he continues. “And each association typically has an operating account and a savings account for reserves.” On average, each association has about $100,000 split between these two. “So if you have 50 associations, that’s $5 million.”

It’s not a slam-dunk business. Property management firms expect a certain level of expertise, says Sanborn. Describing it as a “high-touch, long-relationship industry,” he says it requires the right people with the right connections, and the kind of systems support that these clients need. The bank even has a “deposit production office” to facilitate both sales and service for this group of clients.

Summing up the homeowner association/property management deposit niche, Sanborn spells it out this way: “If you can get in, you get very sticky, low-cost core deposits.”

Tagged under HowTo, Community Banking, Feature, Feature3,