Are you watching banking’s barometer?

Consumers have been hoarding money in checking, and this should drive your strategy

- |

- Written by Mike Moebs

- |

- Comments: DISQUS_COMMENTS

What is really on the minds of consumers and small businesses? Mike Moebs has a barometer to recommend, and it's not saying the same thing that some would have you believe.

What is really on the minds of consumers and small businesses? Mike Moebs has a barometer to recommend, and it's not saying the same thing that some would have you believe.

Right before the Great Recession consumers kept less than $1,000 on average in their checking account. Today the average balance is over $3,600. That’s over a 300% increase.

There are about 359 million consumer checking accounts in the United States owned by about 246 million consumers. That comes to 1.46 accounts per person, each holding over $5,000. Back in 2007 the consumer held about $1,500.

Sailors of old watched the skies, but they also watched their barometers to see what was coming. Bankers watch their markets, but they also have a barometer they can consult, as well. Here’s more about that and what you should be reading from it.

Why are consumers hoarding in checking?

Checking is to financial trends as a barometer is to the weather, in my experience.

A barometer is typically labeled with predictive wording, such as “fair,” “change,” “rain,” and “storm.” In a similar way, checking forecasts the movement and much of the amount of money. We’ll look at the barometer directly in a moment.

My own read of the banking barometer: Consumers are hoarding money because they still sense the economy is not doing well.

The average consumer believes the economy is still in the Great Recession and is reluctant to actively engage by increasing spending.

Here’s what’s on their minds:

• Consumers realize their wages have increased less than inflation, or for the past year less than 1.0%.

• Unemployment (U6) remains high at 8.4%.

• Retail and auto sales are in a slump because the consumer doesn’t want to spend money.

• And, if the consumer tries to obtain interest on what they are hoarding in checking, this ranges from 5 to 10 basis points for an interest paying checking accounts to maybe 40 bps for a savings account or money market deposit account. So why spend?

Strategically, the checking barometer shadows the market.

What does the barometer tell you?

Let’s take a current reading on the checking barometer.

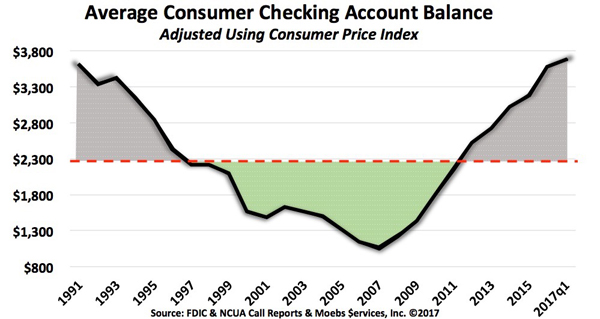

The graph shows 26 years of average consumer checking balances. These numbers are adjusted for inflation with the Consumer Price Index. The dotted red line represents the average or median checking balances, which are just about the same, or $2,200. The data comes from the call reports of all 11,831 depositories.

First takeaway is that the consumer keeps money in checking when times are bad or risky, and little money in checking when times are good.

In the early 1990s the U.S. economy was in a deep recession, as it is now, in the minds of many, in spite of official classifications. The average balance in 1991 was $3,604 and today is $3,676, or 2.0% higher. (Remember, I’ve adjusted the balances for inflation, so you are seeing a true behavioral comparison here.)

Second takeaway is that checking balances have an inverse relationship to the marketplace. Balances are low when the economy is doing well and high when the economy is not doing well.

Third takeaway is the consumer moves very slowly.

From 1991 to 2007, or 17 years, the consumer was engaging more and more with the marketplace. Retail sales went from poor to good to excellent in a 14-year period (less three years of 1991-3 when recession was still gripping the economy).

Starting in 2008 the consumer started to retreat from the marketplace again.

The American consumer’s holdback has now extended into its tenth year—from 2008 to the present—with no indication of re-engaging in the immediate future.

Can barometer both macro and micro?

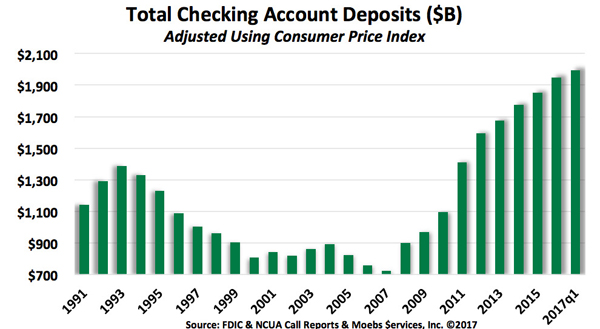

The individual or micro measurement of an average checking account provides a strategic or macro perspective too. The bar graph of Total Checking Balances adjusted for Consumer Price Index provides several key takeaways (and please note that unlike the first chart, this chart covers all checking accounts, not just consumer balances):

First takeaway is the amount of money in transaction accounts, or as economists call it, M1. This comes to almost $2 trillion currently—the highest at any point in this 26-year time series. It is also a historic high since the late 1950s when the Federal Reserve started collecting this data.

Second takeaway is that for the 17-year period prior to the Great Recession the average balance for total checking accounts was $992 billion. Today the total balances of checking accounts are $1.995 trillion.

The difference between the years prior to the Great Recession and today’s total balances is almost exactly $1 trillion. This $1 trillion represents the total amount of money being hoarded since 2008. Many banks, and few thrifts or credit unions, have kept “the hoard” mostly in investments.

Third takeaway is that the $1 trillion being hoarded is split 57% consumer and 43% business. The consumer is hoarding about $565 billion in their checking accounts. The bulk of businesses stockpiling cash are small firms of 25 employees or fewer—there are over 20 million small businesses.

7 points to build action upon

Now let’s tie this all together. The checking barometer suggests the following implications from both a day-to-day or micro perspective, as well as a strategic or macro view:

1. The checking barometer is a concurrent measure.

This means it is not a leading indicator, nor a lagging measure, but what is happening now.

2. The checking barometer bears an inverse relationship to the health of the overall economy, but can be applied locally too.

Individual markets in the overall economy can be doing well and others can be doing poorly simultaneously. Checking balances will reflect this. In markets doing well, financial institutions should expect lower checking balances in these markets. High checking balances show underwater markets.

You can’t assume that balances solely reflect your bank’s competitive stance. You may only be riding a hoarding wave.

3. Many consumers and small businesses still believe they are in the Great Recession.

Many voices have been asking how long the economy’s upswing can continue. The checking barometer is one of the few economic measures supporting the theory that many consumers and businesses haven’t seen it. As the Federal Reserve raises interest rates, it is accentuating that tendency—telling consumers not to spend and small businesses not to invest in capital improvements.

4. Consumers will take a while to get fully re-engaged in retail spending.

Those financial institutions that offer free checking, keep fees low, and promote technological self-service will be the winning depositories as the consumer reenters the marketplace. You must give them all the reasons you can to centralize the deposits they maintain with your bank.

5. Financial institutions offering compensating balances as a way to pay for services provide a winning price strategy for consumers and small businesses.

Compensating balances are often thought of as a big business account analysis tool. Now is the time to use this tool with consumers and small businesses. Don’t skimp on the earnings credit rate for the balances.

6. Strategic planning and budgeting of financial institutions should incorporate the checking barometer for 2018, and beyond.

While consumers and small businesses are slow to move, by 2020 consumers will be engaged and moving toward spending and therefore reducing their average checking balances. So, plan accordingly with slow money movements in 2018 building to a faster pace by 2020.

7. Marketing functions of financial institutions need to engage now, identifying consumers and small businesses having excess money or hoarding.

These folks are the golden geese you do not want to lose as they engage in the marketplace. You can keep them with you by using their balances to pay for services. And, remember these money hoarders can be as important as some or more of your borrowers.

Semper,

Mike Moebs

(Mike will respond to questions at [email protected])

Tagged under Management, Financial Trends, Retail Banking, Blogs, Customers, The Prairie Economist, Feature, Feature3,