A blockchain you can edit?

Debating controversial new prototype in wake of major blockchain bump

- |

- Written by Steve Cocheo

- |

- Comments: DISQUS_COMMENTS

The concept of an editable, redactable blockchain goes against the basic premise many hold dear. But it’s actually a good deal more complicated than this simple photo.

The concept of an editable, redactable blockchain goes against the basic premise many hold dear. But it’s actually a good deal more complicated than this simple photo.

Back in 1970 the plot of a science-fiction thriller called “Colossus: The Forbin Project” centered on the idea of a huge computer being built to manage national nuclear defense. The film’s catch was that to prevent fallible humans’ intervention, once Doctor Forbin crossed a protective moat a final time, the computer pulled up its drawbridge forever. Man could never influence the machine’s decisions again.

As “Colossus” was a thriller, you know that this premise went screwy.

Colossus was designed to be an “immutable” system, one “not capable or susceptible of change,” according to one dictionary.

Immutability is a basic premise of blockchain technology too.

And the recent news of a significant change to that premise is something banks exploring this new technology must weigh. We’ve questioned both a top executive from Accenture, the company behind this new change—the editable blockchain—and William Mougayar, author of The Business Blockchain: Promise, Practice, And Application Of The Next Internet Technology, regarding the details and how it fits into the bigger blockchain picture.

Blockchain and immutability

As we noted in our recent article, “Blockchain: What you need to know,” the blockchain technology world has at least two sides, the philosophical/political and the commercial/pragmatic. Both schools admire the blockchain, but often for different reasons.

At the risk of oversimplifying those views, the first admires the built-in trust and the very “statelessness” of the blockchain technology, hinging on the fact that, under normal circumstances, blockchain’s distributed ledger entries cannot be altered or erased. That same facet of trust plays a big part in the pragmatic school’s favoring of the blockchain.

But some alterations prove unnecessary, while others can be tempting.

Earlier this year, a mini tempest arose in New York over the name of a significant span, the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge. The two-deck suspension bridge connects Brooklyn to Staten Island, and it was named in honor of 16th Century Italian explorer Giovanni da Verrazzano.

Did you catch the typo, there? When the bridge was named, they somehow left out the second “z” from Signore Verrazzano’s name.

Though some Italian groups picked up the protest over the summer, the authorities have declined to change signage and more. And, considering that the bridge has worked successfully for 50 years, not being able to change the name is not really all that critical.

But the thing of it is, the blockchain, one way or another, is about money. And that makes getting things right very important.

And that is what led Accenture and Stevens Institute technologist Dr. Giuseppe Ateniese to develop, and apply for a patent for, the controversial wrinkle of an editable blockchain.

Why the need?

A key point embedded in the word “blockchain” is the chain. That implication—that every transaction in a given chain is linked to the previous one and the next one—is part of what makes the blockchain what it is.

In the conventional blockchain, if someone tries to change what’s in a block in a blockchain, that “breaks the math” of the algorithms that make the chain. Unless enough participants accept the change, the blockchain rejects it, both keeping the chain intact and also establishing a record of the attempted tamper.

If enough participants approve a change, it can be made, and the blockchain will not be broken. However, such changes are not as simple as editing a database, making a word change in a document being drafted by a committee, or repainting a wall a different color. (Not that the latter is always easy when four people all think they have design sense.)

What happens is this, according to Accenture: “If a sufficient number of participants agree to the change, a fork can be added, with one prong ending on or diverting from the faulty block and another prong continuing onward from the corrected block. After a block has been corrected all subsequent blocks must be reconstructed, which can be disruptive and costly and, in some cases, practically impossible.”

There are both “soft forks” and “hard forks.” (This is “fork” in the sense of a “fork in the road,” more or less.) Both involve a change in the chain, in layman’s terms. A hard fork is more extreme, involving a permanent departure from the original blockchain. (From bitcoin.org’s glossary, for technologists: “a permanent divergence in the blockchain caused by non-upgraded nodes not following new consensus rules”)

This is not a theoretical matter.

In June, an issue arose in the community of the blockchain currency called Ether. Hackers stole over $60 million worth of the digital funds from a start-up fund called “The DAO.” This blockchain was designed to execute “smart contracts,” blockchain instruments intended to self-operate without human intervention. (Read a technical blog reviewing this and related issues.)

However, an error in coding enabled the hackers to steal the funds. At least, in a sense.

As recounted in an Accenture report and additional sources, DAO participants stood to lose one-third of their funds. The culprit or culprits have argued through counsel that they should receive that money because the erroneous coding should rule. Actually, some blockchain enthusiasts have even supported this, in the apparent belief that the immutability of the blockchain must rule.

As the Accenture report states, the participants weren’t so inclined, seeing the hack as a “misappropriation of assets.”

What was done instead of just moving on—hardly likely—was setting up a hard fork for The DAO, which occurred in late July. Accenture’s report describes this: “The DAO participants have taken the bold step of adding a ‘hard fork’ to the blockchain at the moment before the theft occurred. One prong in the fork contains the original chain; the other starts a new chain omitting the $60 million loss and reconstructing all subsequent transactions to date.” [Emphasis added]

Yes, you read that correctly. If it sounds a bit like time travel—blockchain can sometimes bring out the sci-fi in one—well, welcome to 2016.

Accenture’s report, Editing The Uneditable Blockchain: Why Distributed Ledger Technology Must Adapt To An Imperfect World, points out that this is not the only potential cause for wanting to make a change to a block in a blockchain. There’s been mischief afoot besides the attempted theft. The report points out that pranks and worse—such as child pornography—have been embedded in blockchains.

Accenture argues that there ought to be an alternative to this state of affairs.

The why of editable blockchain

Taking a hard fork breaks the original chain, explains David Treat, managing director of Accenture’s capital markets blockchain practice in an interview with Banking Exchange. He says this seems something of a blunt instrument to use when there could be a better way, one that is not quite so drastic.

What Accenture and Dr. Ateniese propose is a blockchain that can be changed under appropriate circumstances without breaking the original chain and without creating forks. The new technology, which has been prototyped but not yet implemented in a live application, would be used only in “permissioned” blockchain situations.

Permissioned systems have oversight by a designated administrator under specific rules; the administrator governs who can access them. By contrast, there are also “permissionless” systems, such as the one that Bitcoin operates under. Accenture does not propose use of the new technology on permissionless systems, where it believes complete immutability is critical.

Accenture’s Treat says the inventors don’t foresee any “free-for-all,” in his words, of editing blockchains using the new tech. Indeed, he says that the technology has been conceived as enabling changes in what he calls “break glass, pull down handle moments.” These situations could come about through human error or bad coding; pranks or fraud; or identification of critical bugs or weaknesses in a blockchain. Some legal issues, such as European privacy laws, may also have an impact. The Accenture paper goes into considerable detail on these points.

As designed, the users of blockchains established under this technology would not be able to change anything. For them, the blockchain would remain immutable.

On the other hand, designated administrators of a given blockchain, acting under agreed-upon governance rules, would be permitted to edit, rewrite, or remove blocks of information without breaking the chain.

“We are not suggesting that this would be a frequent thing,” explains Treat. “The phrase I like to use is ‘pragmatic immutability’.” He says he’s been asked who gets to hold the key that would unlock editing capability, and he makes clear that this is intended to be tightly controlled.

“Think nuclear launch codes,” says Treat. The editable blockchain, he said, is not meant to be like an editable database that people are constantly accessing to make changes. The intent is to better fit blockchain to the enterprise user, according to Treat.

Treat says Accenture has had queries from regulatory bodies. In addition to financial services companies, the firm has also had interest from other industries, among them health care. Treat says he expects it will be a few years before there’s widespread adoption of this blockchain variation.

The how of editable blockchain

Many people speak about the blockchain and write about the blockchain, and, frankly, for many of us, it is a black box. In fact, spend a little time on a site meant for people who really understand the guts of blockchain technology and you quickly realize that this is a highly technical affair with its own lingos and protocols.

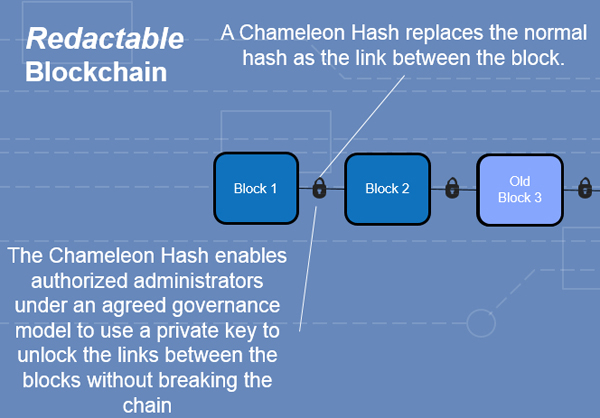

However, a schematic understanding of how the editable blockchain would work is summarized in Accenture’s report and accompanying materials.

The following graphics illustrate the general principles; a critical element is "the chameleon hash":

Assessing the editable blockchain

Author and tech investor William Mougayar says there’s no need to get “worked up” about the idea of a blockchain that can be edited. One noted British commentator, David Birch, in a fairly technical critique of the invention, summed up by calling it “a chocolate teapot.”

“If the market needs it, it will get adopted,” says Mougayar. “If it scratches a particular itch for some customers, then so be it, and that's how it will get used.”

Blockchains are multi-faceted, Mougayar points out.

“They aren't just about distributed ledgers, cryptocurrency, immutable records, trustless validations, multi-signatured transactions, smart contracts, etc.,” he explains. “So, it is expected that some users may not like certain features whereas other features might be more liked.”

Mougayar says the nature of the technology is such that new wrinkles like Accentures should be expected.

“There is not one single way to implement blockchains, and there will never be,” says the author. “A blockchain has modular features, and that leaves room for their unbundling and the creation of variations.”

Reached via email during an industry conference, Mougayar said the following in answer to emailed questions:

Banking Exchange: What have you heard in the blockchain community about Ateniese and Accenture’s development?

Mougayar: I've read most of what's been said about it on social media and in other blogs and newspaper reports. Some of the arguments from the naysayers indicate that they don't understand how big companies work.

The blockchain in its fullness is really about replacing a good chunk of financial intermediaries and incumbents. Therefore it is not surprising that in their defense, they will decide what they like and throw out what they don't like about blockchain features.

And some have misinterpreted the intent of this editable feature, because they have not looked beyond the headline.

Banking Exchange: How “big” is this in terms of blockchain’s evolution? Is this something that could cause a split in blockchain’s application, potentially creating two subset technologies?

Mougayar: We don't know how big it's going to be until there is adoption in real implementations.

In theory, many ideas look great—and there is no shortage of blockchain theories. I don't think the scope of this idea is such that it creates two subset technologies. This is just about one implementation variation.

Banking Exchange: Accenture’s David Treat stressed in my interview with him that this was intended for “in case of emergency break glass” moments. Makes sense up front. Do you think it will stay that way?

Mougayar: This is not a flippant idea that Accenture has dreamt up to get attention. The company works closely with large clients, which is where the need came from. And there was a sufficient level of detail in the inventors’ descriptions of how use cases would unravel. That demonstrates their seriousness.

Banking Exchange: In trying to understand this concept, I tried to draw a parallel with Wikipedia, where there is an ongoing list of every change ever made, who made it, etc., behind the “view history” tab. Accenture resisted this comparison, saying that the Wikipedia setup was more like classical auditing of database management. I get that now.

What analogy would you draw for an editable blockchain?

Mougayar: It's a release valve.

Banking Exchange: Ultimately, do you think this will prove to be a useful development for blockchain technology?

Mougayar: Again, it's an implementation detail in the grand scheme of things.

That said, the only thing I don't agree with is when Accenture says that "Absolute immutability will slow blockchain progress." That's an engineered marketing statement that is meant to create some “FUD” with customers [fear, uncertainty, and doubt]. [Editor’s note: The reference is to an opinion article that Accentures David Treat published Sept. 20, 2016, on Coindesk.com]

Blockchain features will be used in a variety of ways. The only thing slowing down blockchain progress is real end-to-end implementations and more aggressive use cases for it.

Download Accenture’s Editing The Uneditable Blockchain [For mainstream readers]

Download technical paper by Dr. Ateniese et al [For expert readers]

Tagged under Technology, Blogs, Reporters Notebook, Blockchain, Feature, Feature3,