What’s wrong about millennial credit scores

Credit education, critical to financially “growing up,” is ignored. But scoring itself needs fixing

- |

- Written by Amrita Vir

- |

- Comments: DISQUS_COMMENTS

A new generation will take financial services into the future. In the new blog "Next Voices" a rotating group of bloggers of the younger generation will share what they are learning, thinking about, and doing. Proposals from guest bloggers are also invited. Please email [email protected]

A new generation will take financial services into the future. In the new blog "Next Voices" a rotating group of bloggers of the younger generation will share what they are learning, thinking about, and doing. Proposals from guest bloggers are also invited. Please email [email protected]

I received my first credit card when I was in college. The card came from a department store. A clerk had told me that using the store’s credit card would save me 15% on my purchase. I was a financially strapped college student, so a 15% discount sounded pretty good. Little did I know the havoc I was about to wreak on my young financial life.

Of course, I missed a payment.

Okay, maybe two.

I cancelled the card after realizing that this error had completely tanked my credit score. Since then I have only been able to qualify for a couple more credit cards after many years of being rejected by card companies.

I would like to think that I have become a more responsible adult since that first missed payment. I finished college with a finance degree, found a job as a consultant, rented four different apartments, and am now pursuing graduate studies.

But even after almost ten years, my credit score does not reflect any of this “growing up.”

Life after “credit fumbles”

Researching this, I find I am not alone. This is relatively common among millennials, of whom 68% have committed a “Credit Fumble” before they turned 30, according to a recent report by Credit Karma. The same percentage of millennials say they did not understand credit scores when they obtained their first credit card, and 75% felt that these fumbles have adversely impacted their lives.

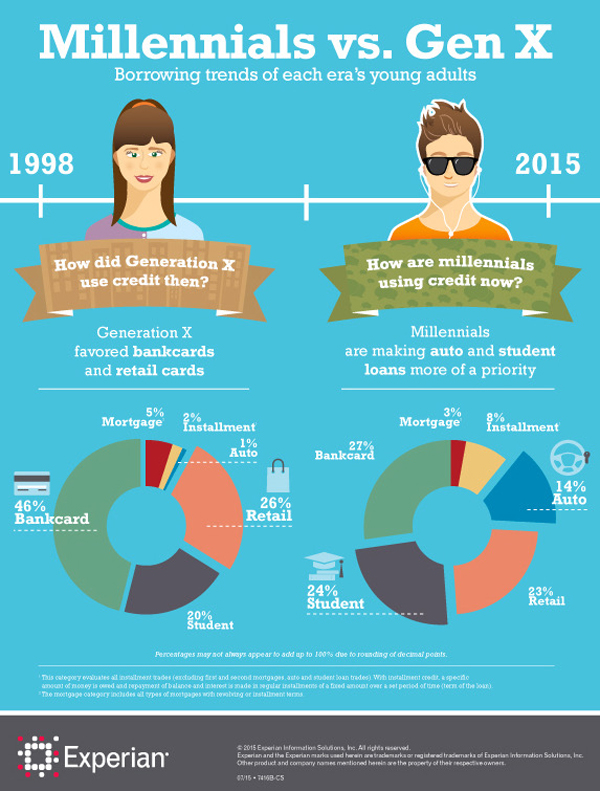

Older generations like to roll their eyes and say that young people are just irresponsible, and that that’s why we have lower credit scores. According to a report by Experian, however, we can compare credit habits of Generation Xers in 1998 to millennials in 2015. In fact, millennials are taking out more credit for studies—and less credit for retail spending— than Gen Xers.

The problem of younger people having lower credit seems like a systemic, rather than generational problem. Why is this the case?

The problem

On one hand, we millennials have a problem with financial education. Personally, I never had any financial literacy training in grade school. Perhaps the only financial education I received before college was from my father, an entrepreneur, and my grandfather, who let me “borrow” quarters to buy ice cream.

I’m not alone because according to the same Credit Karma report, “only 28% of people surveyed received some type of personal finance education before college, with the majority of that education (58%) coming from parents.”

However, studies about the impact of financial education in schools are contradictory and inconclusive.

One 2014 study by the Council for Economic Education shows that financial education mandates in schools increase credit scores. However, another working paper by my very own professor at Harvard indicates that the long-term impacts of these same mandates are negligible. This has seemed to result in regulatory stagnation when it comes to implementing any meaningful policy around financial education.

So if we are not trained in personal finance in school, then we must learn through experience. Certainly, in my case, I was burned with my first credit card, and now I know much better. This experiential learning continued as I took out student loans, bought a car, and rented my first apartment.

The problem with gaining experience is that it takes time, and my credit score has not been able to keep up.

Credit is rear-view mirror

Finally, our credit scoring system in the U.S. is inherently rigged against young people. This is because FICO focuses on historical metrics rather than forward-looking opportunities.

The Fair Isaacs Corporation shows the breakdown of FICO scores:

• 35% of scores come from payment history.

• 30% from amounts owed.

• 15% from the length of credit history.

• 10% from new credit obtained.

• 10% from credit mix.

That means that at least 50% of our FICO scores comes from our past credit experiences.

However, it is still not entirely clear to me how each of these categories is defined and how they impact my final FICO score.

I can pay $29.95 per month to obtain my score from FICO directly, but there are three different credit bureaus. Experian, TransUnion, and Equifax each provide me with a slightly different FICO score.

As a result, I am perpetually confused about which score is accurate. (Are any of them accurate? I wonder, given that they don’t reflect my understanding of credit now.)

Furthermore, not all sources of credit report to the credit bureaus. Often, my parents serve as my bank, giving me loans to make rent payments whenever I am in a bind. Dad doesn’t charge much interest, but I always pay him back. Where does that show up in my FICO score?

According to trends tracked among age groups by Credit Karma, low credit scores persist until people are well into their 40s, where the average Credit Score rises from less than 630 to more than 645.

Counterintuitive: More borrowing builds credit score

The conundrum here is that we can only have a good credit score by continuing to get new credit.

If we start off our financial lives by making good credit decisions—and don’t stumble due to subsequent bad decisions or life events—our credit score rises and stays up by a self-reinforcing cycle of guaranteed access to credit.

However, if we do stumble, our score drops, and access to new credit is constrained. This leads to sub-optimal credit score stagnation with lasting impacts.

Moving forward

What can bring about some change?

First, we need better financial education.

The public education system has not stepped up to improve financial literacy for grade schoolers, and the burden largely falls to parents.

More importantly, I think, we need to rethink the ways in which we assess creditworthiness.

Perhaps financial literacy needs to include a more explicit and transparent way to show how our credit is calculated.

Perhaps age should be considered in reviewing credit requests. For example, a 40-year old with a robust credit history, who has a FICO score of 630, may be denied a loan. However, a 20-year old student with a limited credit history and same 630 FICO score could be allowed a credit card because the lender has taken the young age and thus, future earning potential of the student into account.

Perhaps, we can think of more creative and more effective ways to assess creditworthiness than simply looking at past performance.

These thoughts aren’t new to me. The credit bureaus have started offering supplemental scores to address these arguments. For example, TransUnion released its CreditVision Link in 2015, which includes data on account management, tax records, address stability, and payday loans.

Alternative credit bureaus are also on the rise. Companies like Pay Rent, Build Credit (PRBC), CoreLogic CREDCO, and LexisNexis are offering scores that include data from cable and telecom companies, gas and electric utilities, and insurance providers.

A few companies, especially fintech startups, have been experimenting with alternative forms of credit assessment to bring young people into the credit world. Some are using mobile phone data for microcredit (e.g. Cignifi and FirstAccess). Some use education level for student loan refinancing (i.e. SoFi, Earnest, and CommonBond), and some are even using social media (Lenddo) and online data and machine learning (Kreditech).

Many of these efforts are happening around the globe, including such fintech hotspots as Singapore, Israel, Australia, East Africa, the U.K., and Nordic countries, as the regulatory environments are much more amicable to financial innovation.

How banks can benefit

Banks have huge opportunities in this environment.

In regard to financial literacy, banks are the obvious partners. By creating resources for young people, be they financial literacy classes, gamified financial tools, or just being able to take out small forms of credit at an earlier age, banks could build trust with their future customers before other competitors get in the way.

Banks will also be advantaged by using alternative methods to assess the credit of their younger borrowers. The result will be more loans with more accurate measures of risk and appropriate interest rates.

This is, however, a limited time opportunity. If banks don’t act soon, these millennial customers may turn to different sources of credit that will assess them along metrics that they understand and through which they can find success.

Personally, I would rather refinance my student loans through SoFi or CommonBond to pay down my grad school debt than a traditional bank.

Why? Thus far, a traditional bank just sees me as a number, a FICO score that defines me by my past failures.

Companies that use alternative data on the other hand, take my education and future income into account.

They see me not for my past, but for my potential.

Tagged under Consumer Credit, Retail Banking, Risk Management, Blogs, Customers, Credit Risk, Next Voices, Feature, Feature3,

Related items

- Banking Exchange Hosts Expert on Lending Regulatory Compliance

- Merger & Acquisition Round Up: MidFirst Bank, Provident

- FinCEN Underestimates Time Required to File Suspicious Activity Report

- Retirement Planning Creates Discord Among Couples

- Wall Street Looks at Big Bank Earnings, but Regional Banks Tell the Story