Durbin amendment pushes bank growth

SNL Report: Is $20 billion the new $10 billion?

- |

- Written by SNL Financial

By Kiah Lau Haslett and Salman Aleem Khan, SNL Financial staff writers

There is no love lost between banks and the Durbin Amendment, but for the most part institutions appear to have accepted and managed around the vilified debit interchange fee cap during the four years following the passage of the Dodd-Frank Act.

Bankers have long criticized the Durbin Amendment for slashing debit interchange fees at institutions with more than $10 billion in assets. The move, part of the Dodd-Frank Act, is one of the major factors causing management teams at midsized banks to weigh the merits of growing above the $10 billion mark. Some have decided to stay under the limit for now and manage their balance sheets; some are strategically timing deals that send them over the brink; and still others are charging ahead, with the view that $20 billion is the new $10 billion.

Looking back at Fed’s rule

In the summer of 2011, the Federal Reserve voted to limit debit interchange fees to an average of 24 cents per transaction, down from approximately 44 cents, for financial institutions and their affiliates with more than $10 billion in assets.

It was "well-recognized" among industry players that there would be a large drop in revenue, although some believed that affected banks would put limits on free checking accounts and emphasize prepaid cards and credit cards that are exempt from the Durbin Amendment, said David Stein. Stein, a director at Promontory Financial Group, spent 12 years as an attorney and managing counsel at the Federal Reserve, and worked on the draft of Durbin.

There was no shortage of disparagement and criticism from bankers on Durbin prior to the final rule. Bank of America Corp. President and CEO Brian Moynihan said on the bank's second-quarter earnings call back in 2010 that the statute was "a very unusual event in American history" as lawmakers attempted to "regulate a particular transaction between two businesses to only allow … [the] recovery of cost."

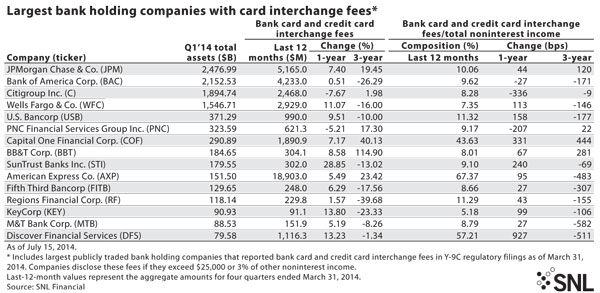

Bank management teams estimated that millions of dollars would disappear from interchange revenues, with amounts varying based on the size of the retail business. The impact appeared on bank income statements for the first time in the fourth quarter of 2011. In the case of Bank of America, debit card revenue fell by $430 million in the fourth quarter of 2011, according to the company's Form 10-K for 2011.

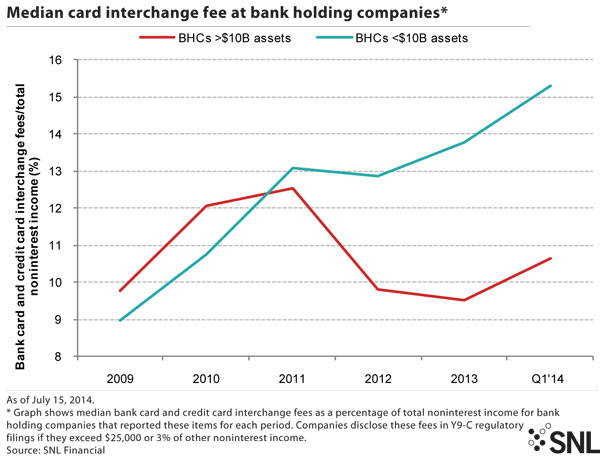

The median bank card and credit interchange fees at banks with more than $10 billion in assets peaked in 2011, at 12.55% of total noninterest income among companies that reported this information for each period. Banks with less than $10 billion in assets reported a median of 13.07% in the same period, according to SNL data. Companies disclose these fees in Y9-C regulatory filings if they exceed $25,000 or 3% of other noninterest income.

Those figures have continued to diverge. In the first quarter of 2014, median bank card and credit interchange fees at reporting banks with more than $10 billion in assets totaled 10.64% of total noninterest income. At reporting banks with less than $10 billion in assets, median bank card and credit interchange fees totaled 15.29% of total noninterest income.

Impact on pricing

"Debit cards [are] a profit-neutral product—banks don't make money on debit cards any longer, so even if they increase their market share or their volumes, they're not making incremental revenue on having more accounts and more transactions on the debit card itself," said Madeline Aufseeser, a senior analyst at Aite Group. She added that institutions still want to grow the debit card business because consumers consider it their primary banking relationship.

The revenue shortfall trickled down to consumers in the form of pricing changes to checking accounts, and also through banks' increased emphasis on prepaid cards. Some banks raised the minimum balance requirements and increased monthly service fees, which she said caused some consumers to opt out of traditional checking accounts.

Impact on deal size

The interchange fee cap has prompted executives at community banks below $10 billion in assets to weigh the millions of dollars in revenue shortfall against increased growth opportunities. Banks that cross the year-end assessment deadline are hit with the cap in July of the following year. But Stein pointed out that banks are under contradicting pressures to stay small or go big. Those nearing $10 billion in assets must weigh adding scale that would help offset regulatory costs against the debit interchange fees.

John Allison, chairman of Home BancShares Inc., recently spoke about the bank's conundrum, given its roughly $6.8 billion in assets. He said during a conference in March that the interchange fee would cost about $6 million a year if the bank went over the $10 billion threshold.

"I don't know if we want to do that [go above $10 billion] or not, we'll see. When I say that, my people laugh, because if I find a right deal, they know I'll probably do it," Allison said, according to a transcript. "But the key is, there's nothing wrong with being $9.5 billion, running the 2% ROA, running the sub-40 efficiency ratio and [raising] your dividend and [rewarding] your shareholders; there's nothing wrong with that."

Evansville, Ind.-based Old National Bancorp is a name that has flirted with the threshold several times through acquisitions, but has thus far managed to stay below $10 billion. Management has been vocal about its growth—namely its desire not to sneak over $10 billion and become "half-pregnant," as President and CEO Robert Jones has said in the past. To make up for the $2 million to $3 million per quarter that the bank would lose due to the interchange cap, Jones said the bank would have to hit $13 billion or more.

In January 2014, Old National announced a deal with Ann Arbor, Mich.-based United Bancorp Inc., which had $918.8 million in assets as of Sept. 30, 2013; its expected completion is in July. Jones said in a deal conference call at the time that the acquisition would unequivocally push it above the $10 billion mark, subjecting it to the Durbin Amendment beginning July 1, 2015. But management contended that growth ambitions outweighed cost concerns associated with the amendment.

"We always said [Durbin] is something we would have to deal with," James Ryan, executive vice-president and director of corporate strategy told SNL. Ryan said that the Durbin amendment would not impact Old National's decision to do a deal. "It [is] really something that hasn't affected our overall corporate strategy or our M&A strategy."

Old National's acquisitive bent continued, when in June the bank inked an agreement with Lafayette, Ind.-based LSB Financial Corp., which had $366.1 million in assets as of March 31; it is expected to close in November or December 2014. Adding just the acquired assets to first-quarter 2014 figures, Ryan said the bank would be around $11.6 billion by July 1, 2015; organic growth would further boost that number.

The $20 billion club

Meanwhile, some banks that have crossed $10 billion and grown to a size that makes up for the interchange income shortfall are now eyeing a new target size: $20 billion.

Executives at several institutions have noted that once over $10 billion, community banks should aim to grow further in order to spread regulatory and compliance expenses across a broader revenue base.

While Old National does not have a specific target asset size, Ryan said management has told investors it envisions itself being a $20 billion or $25 billion bank. Beyond $25 billion, a bank could begin a march to $50 billion in assets, when it is designated as a domestic systemically important financial institution. Ryan added that Old National's acquisitions have been "relatively small" and mostly under $1 billion in assets, so it will take some time for it to hit the targeted range.

Old National is not alone in wanting to grow to $20 billion. IBERIABANK Corp. CFO Anthony Restel said at a conference in May that it is imperative for banks to grow well beyond the $10 billion asset level to absorb the added expenses that come with a host of new regulations.

"I think being closer to $20 billion is better than being closer to $10 billion," Restel said.

IBERIABANK had approximately $13.56 billion in assets at March 31.

BancorpSouth Inc.'s Chairman and CEO James Rollins III noted at the same event that the bank's $13.14 billion in assets may be too small to fully offset the additional costs associated with being larger than $10 billion in assets.

"We certainly have added cost and burden to our company to be over $10 billion," Rollins said at the event. "And I can tell you that cost and that burden is not being levered enough at $13 billion and probably not being levered at $15 billion."

Tagged under Management, Financial Trends, Payments, Cards, Feature,

Related items

- Banking Exchange Hosts Expert on Lending Regulatory Compliance

- Merger & Acquisition Round Up: MidFirst Bank, Provident

- FinCEN Underestimates Time Required to File Suspicious Activity Report

- Retirement Planning Creates Discord Among Couples

- Wall Street Looks at Big Bank Earnings, but Regional Banks Tell the Story