M&A: Waiting at the crossroads

Pace may be slow, but mergers and acquisitions now core part of the business

- |

- Written by Steve Cocheo

Merger chatter is now a constant, even though the deal pace hasn't surged. Many factors have all banks but the very largest weighing "Buy up?" or "Sell?"

Merger chatter is now a constant, even though the deal pace hasn't surged. Many factors have all banks but the very largest weighing "Buy up?" or "Sell?"

Bankers of a certain age may recall an original Twilight Zone episode called “The Rip Van Winkle Caper,” a play on the Washington Irving folktale. In the sci-fi story, a gang led by a scientist pulls a gold heist, hibernates for a couple of decades, and wakes up to find that gold is worthless.

Veteran banker Howard Jaffe thinks bankers, especially community bankers, have been going through their own rude awakening, not from hibernation, but preoccupation.

“The banking model really changed during the financial crisis,” says Jaffe, president and COO of $1.1 billion-assets Inland Bancorp, Oak Brook, Ill. “Banks were so focused on basic survival skills that we weren’t paying attention to the fact that the model was changing.”

A major part of the shift concerns technology, and its exponential rate of change, but also the yin-yang relationship of the banking model vis-à-vis the customers bank seek and serve.

“It’s permanently changed,” says Jaffe, and that has put many bankers in the position of being open to considering acquiring other institutions or selling to another bank. Part of the stewardship for shareholders has become seeking the best deal for ownership.

“It’s a responsibility for a banking organization’s management and board to look at all opportunities that are available to bring some value to investors,” he says. “If that means acquisitions, one must look at those. At the same time, if that means the possibility of a sale, you should look at that as well. So we look at both.”

This puts today’s bankers at a kind of crossroads, where opportunities for a change in direction will constantly be presenting themselves and demanding decisions.

Everyone knows the score

Take the Chicagoland market where Inland does business. Jaffe says there are still many banks of all sizes doing business there. The level of merger-oriented chatter, and phone calls from investment bankers and other deal makers, is constant. Discussions at some level are always taking place.

“The pace of transactions is slow, and the discussions don’t always translate into deals,” says Jaffe, but M&A looms constantly. He says banking has become a small industry, in the sense that all players know or know of each other, at least in a given region, and everyone knows the score.

Further complicating the picture, says Jaffe, who has been through many mergers in a long career, is that real deal making defies the tables one sees about pricing and values.

“There’s a wide range of pricing considerations out there,” says Jaffe. “Price to tangible book is just one component.” He says every deal is unique and often hinges on the metrics of most interest to the potential buyer. For example, a prospective purchaser may most want deposits. But not all deposits are created equal, so the mix of funding that a target bank offers must be analyzed. “You have to look beyond comparisons with other deals,” says Jaffe. “This is not a black-and-white scenario, there’s a lot of gray.”

Overlay all this with the industry’s ongoing turmoil involving all kinds of factors: new competition, including the fintech wild card; evolving strategies; clashing views on the value of geography in deal making and the importance or lack thereof of branches; sometimes uncertain readings of regulatory attitudes on bank size; the rise of compliance issues as a major potential deal breaker or delaying factor—or deal motivator; and one of the most uncertain business environments seen in decades, encompassing ultra-low interest rates and the ripple effects of low oil prices.

“Headwinds” is how Jaffe sums up all of this picture.

Matter of mindset, timing, conditions

Deals are getting done. The numbers, talks with bankers who have done them, and interviews with players who help them get done, confirm that. But the tsunami of anticipated M&A has not materialized.

“I’m not seeing an explosion,” says community bank advisor Jeff Gerrish of Gerrish McCreary Smith. “But it’s been a steady stream.”

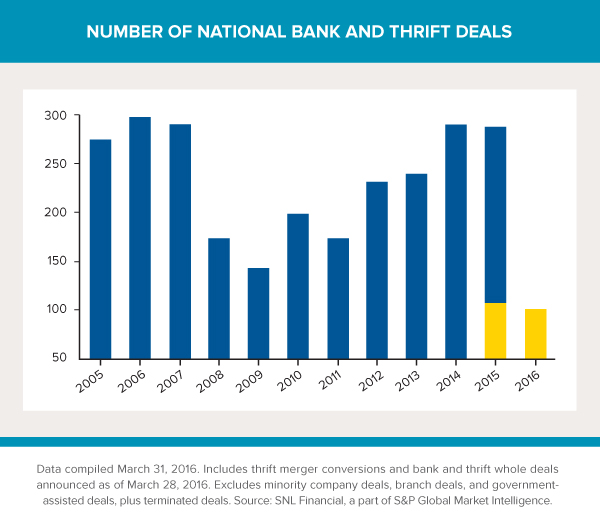

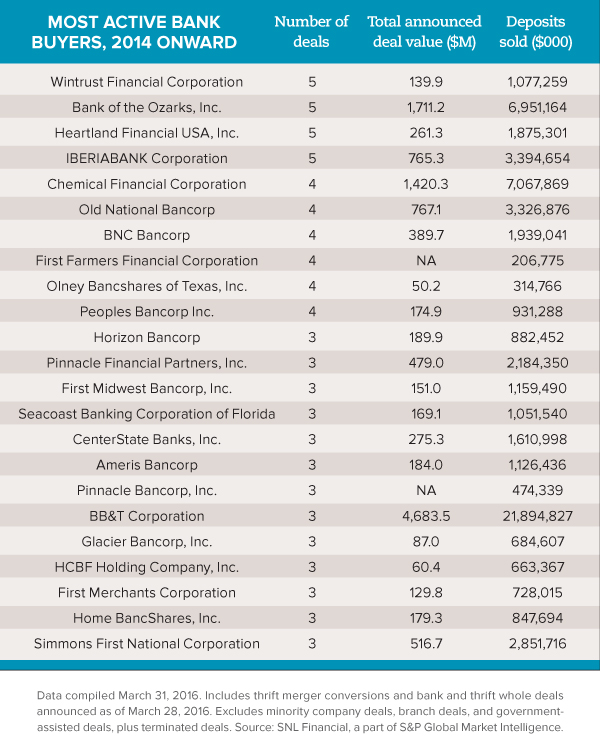

The average of the total of first-quarter nonassisted deals from 2010 to 2016 is 48, including a 2010 low of 27 and a 2015 high of 67; 2016 comes in toward the higher end, at 60. Deal count came to 283 at the end of 2015, down a trifle from 2014’s 285. (Data is from SNL Financial, a part of S&P Global Market Intelligence.)

We asked consultants, investment bankers, and bankers what they’re hearing, seeing, and doing in regards to M&A.

Jay Brew of Seifried & Brew, LLC, who also is a community bank director, says while he hears frustration about regulatory compliance burdens, he doesn’t hear much interest in selling.

“There’s a lot of talk around,” says Brew, “but I’m not hearing, ‘We want out of here.’ Instead, they say they want to buy something. But I’ve heard some people say that for years, and yet they never do a merger.”

On the other hand, potential sellers tend to be very careful about what they say about their thinking, according to banker David Doedtman, president and CEO of $345 million-assets Washington Savings, Effingham, Ill.

Doedtman, whose bank acquired a fellow mutual institution last year, explains that these institutions don’t want to risk word getting out ahead of any deal, and merger-averse depositors deciding to vote with their funds.

The aging of leaders, board members, and investors appears to be playing a part. This seems to go beyond the regulatory fatigue that was talked about a few years ago. While regulators have been harping on management succession for years, even the die-hardest holdouts are beginning to come around.

“The pace seems to have picked up, and I don’t think that anyone is going to run their bank until they are 90,” says community bank investor Joshua Siegel, chairman and CEO at StoneCastle Financial Corp. This factor of simple physical age dovetails with two other trends.

“The role of being an empire builder can be fun,” says attorney Mark Kanaly, partner at Alston & Bird LLP, “but the time can come to monetize it.”

One is a less-discussed effect of the financial crisis. The crisis itself, and some of the damage done to the industry’s image, left a hole.

“We lost a generation of community bankers that moved into other industries instead of community banking, and that’s coming home to roost,” says Robert Flowers, partner, Hunton & Williams LLP. The attorney explains that while some C-suite officers can be replaced, such as CFOs, the availability of seasoned but younger CEOs and COOs proves harder. This drives some thinking about selling.

More financially, there are signs when it is time to consider a sale. “If you have to completely redefine the bank, then the model has matured,” suggests Collyn Gilbert, managing director and analyst of midcap banks in the Northeast at Keefe, Bruyette & Woods.

A bank that has plucked not only low-hanging fruit but also mid-range apples should think about selling, she adds. Today’s flattening yield curve facilitates thinking this way, she explains. “Not many bankers think that way,” says Gilbert, “but if I were running a bank, that’s what I’d do.”

The walking dead

A consideration that cuts two ways comes from StoneCastle’s Siegel. While he’s a booster of community banking and its future, he also is a realist where specific institutions are concerned.

Siegel says in some communities, there are more banks than viable business. Typically, one banks owns most of the market share, one does well for itself, and the third is “walking dead,” says Siegel. Both he and Gilbert suggest one of the stronger players snap up the weakling.

“This lets you take out irrational competition,” says Gilbert, and potentially bring down deposit pricing.

Utilization of capital also plays into the thinking of potential acquirers, says advisor Gerrish.

“People who have excess capital want more bang for their bucks,” he explains. The appeal of a merger is more revenue from the same fixed base of costs, and further deployment of capital.

A factor that hovers out there, often unresolved, is private equity investment. These players went in during or just after the crisis, and those who aren’t already out want to realize their returns and move on. They want to be bought out, though offers are not readily coming, says Gerrish, who notes that private equity isn’t making fresh investments in community banks anymore.

In some cases, private equity is encouraging banks to orchestrate their own takeout, perhaps by launching an initial public offering, but Brian Marek, partner, Hunton & Williams LLP, says the poor current IPO market doesn’t make this practical.

Buyers from where?

What about interest in acquiring banks by other, nonbank organizations? Given the increasing urge of fintech players, for example, to partner with traditional banks, have any been interested in buying one? “Fintech companies are waking up to the fact that they can have a funding source that they can control,” says Gerrish, which they find appealing. But Gerrish and others who have explored such deals find that fintech players get spooked by banking regulation.

By contrast, mortgage banks, subjected to increased regulations in the wake of the Dodd-Frank Act, have been interested in bank acquisitions. “They tend to pay a little higher,” says attorney Flowers, “because they want a bank charter, and buying a bank is much easier than trying to do a de novo bank.”

Actually executing such deals, however, proves a slow process, Flowers adds. Regulators have exhibited concerns about mortgage banks buying banks—they don’t want them “to blow up the balance sheet,” he explains.

Cross slowly

So we have lots of chatter and a laundry list of genuine reasons for deals. What we don’t have is that tsunami.

That M&A is now a core part of the business is acknowledged. “Many banks have spent time shoring up their capital and they have dry powder to buy other banks and jump-start their growth,” says consultant Peyton Patterson, a former banker with extensive experience with mergers. “It’s become part of the model.”

“There are still a lot of banks to buy,” says stock analyst Richard Bove, vice-president, equity capital markets, financial sector, at Rafferty Capital Markets, LLC.

But a consensus seems to be forming that no flood of mergers will occur. Instead, says Patterson, “consolidation is going to be a slow, gradual grind.”

Part of the reason for this trend is that acquirers appear to be much pickier than they once were. Hunton & Williams’ Marek says buyers used to have their top five banks they’d like to buy, but were willing to drop to one in their top ten or 15 if none of their favorites wanted to play.

Now, with fewer chairs in this game of musical banks, an uncertain economy, and other questions, Marek says that buyers proceed with more caution. “Now, they’d rather keep their powder dry for their top five, and not settle for something lower on their list.”

For sellers, there is sometimes reluctance to sell at current prices, even if selling is what they want. “They just can’t justify selling at current prices, compared to what banks were getting 10 to 15 years ago,” says attorney Kanaly.

Marek blames buyer and seller hesitancy on low interest rates and the oil and gas situation. Overall, he says, “they are waiting for a market check, based on the first and second quarters, before they pull the trigger on any M&A deal.”

Speaking more generally about stock market conditions, analyst Bove asks, “When will the Fed realize that it needs to increase confidence in the banking system?” With stocks in publicly traded banks selling at fraction of their value—50% to 60%—he says, this is no academic matter, because indications are that many acquirers would prefer the currency of stock rather than cash, or at least a blended stock-cash deal.

Pricing realities

In a recent edition of a real estate broker magazine, a veteran agent explained that one of the biggest hurdles to successfully selling a home was persuading the homeowner to begin offering the house at a price commensurate with the market. Once up for sale, the agent said, it ceased to be a home and became a commodity.

Selling a bank that a CEO, board member, or local investor has been involved with for a long time may bring a similarly necessary adjustment of perspective. While every deal is unique—a valid point from Inland’s Jaffe—consultant Gerrish says much of the basic price-setting for a deal is a mathematical process based on the bank’s numbers.

Seller thinking may not start there, however, even in a post-crisis atmosphere. Emotion seems to govern much thinking about pricing a sale. No one likes to see themselves or the fruit of their efforts as a mere commodity, and the smaller a bank, “the more special they think they are,” says consultant Patterson. “But I am 100% certain that the valuations of the past will not come back.”

Sellers holding off until the return of twice times book may wait forever, suggests attorney Flowers. Even some sellers who want to wait for 1.5 to 1.8 times book may be overly optimistic, he adds.

Bank investor Siegel sees the recent steady state of consolidation continuing for some years, and he believes the industry will settle out, for a time, at around 4,500 banks. Gerrish concurs.

“That’s no good,” says Siegel, but he’s a realist. Banks that hold out until the industry’s population levels off may enjoy an incremental gain due to scarcity value—fewer targets to be bought. But there also is the risk that the bank’s franchise will not look as attractive.

What happens among larger banks is a backdrop to what happens among community banks. While there is a question, in light of “too big to fail,” of when big gets to be too big, plenty of larger banks can still get together. “Anyone $50 billion or below can still do deals,” says Bove. “I think you’ll see some more large bank M&A,” adds Keefe, Bruyette & Woods’ Gilbert. “There aren’t a lot of earnings levers left for large banks to pull.”

Bove thinks talk of culture and cultural affinity in the big bank M&A space is mere lip service. Referring to one big bank that stresses cultural fit when it talks merger, he dismisses it as “baloney.” Says Bove, “Nobody cares about culture anymore.” Big players seek more customers for more revenue.

That’s not so much the case with community or midsize banks.

Due diligence for all

In bank M&A, the concept of due diligence is evolving. Once centered chiefly on credit and on the acquisition candidate, now buyer and seller inspect each other, and this applies whether the proposed deal is for cash or for stock.

Beyond the traditional concerns, “compliance from a due diligence standpoint has really picked up,” according to Gerrish.

Compliance surprises can be reputational trouble, and they can be expensive both for legal expertise as well as fines or penalties. Compliance issues involving matters like fair-lending investigations or CRA challenges can delay a deal by years, at the extreme.

Regulators have been known to use a pending or possible deal as leverage to bring a bank to the table. And anyone who will hold the stock of an institution post-merger must be concerned about successor liability—an acquisition erases no compliance sin of the seller.

Today, increasingly, there is due diligence of the buyer by the seller even on financial grounds. No seller wants to find out that there’s some financial issue that’s going to make regulators delay or halt a deal, and, ultimately, sellers want to be sure that the buyer is good for the offer.

Overall, says Hunton & Williams’ Marek, if a deal falls apart these days, the cause more typically is an issue uncovered in reverse due diligence, and it’s typically a regulatory matter.

Leaders on both sides must bring the appropriate expertise to the table, and this includes IT, according to Patterson. Nasty surprises can arise in processing, and frequently, it’s helpful for the acquiring bank to bring its key IT vendor into the picture to assess what kind of conversion it’s in for. “Bankers have to understand that unanticipated merger costs can blow your deal,” she explains.

Does geography really matter?

Concentration on fintech as well as digital banking has a way of overshadowing what is actually going on today. For all the zest of electronic finance, banking consists of a lot of very basic, unsexy stuff that nonetheless makes our economic world go around.

So the question, “Does geography still matter?” in an M&A context is relevant, but easily answered. One banker’s response puts much in a nutshell.

“Digital is an important part of our delivery system,” says Bill Docking, “but it’s not the only part. It’s very important, still, to have relationships with your customers, and it’s hard to do that digitally.”

Docking’s family holding company, $477 million-assets Docking Bancshares, acquired Relianz Bancshares last year. Docking explains that the two banks had worked deals together and that management liked the other bank’s style. It made sense to buy Relianz as part of an effort to expand and solidify the acquiring organization’s presence in the Wichita, Kan., market.

The deal was very much about physical footprint, and in time, Docking sees further deals to fill in the company’s footprint and to judiciously expand its physical reach.

“We want to continue to grow,” he says. “Some of that growth will come from acquisition. Fit is very important to us, so we are continually sifting and sorting what’s out there.” Docking expects to find more opportunities, explaining that “there’s a window of opportunity that may close soon for banks with aging managements and aging ownerships that don’t have solid succession opportunities.”

You can’t touch on geography without branches coming up. From the viewpoint of a larger bank analyst like Gilbert, branch networks can be an expensive, increasingly less important asset for retail organizations. “More banks are saddled with real estate than there are banks looking for real estate,” Gilbert points out.

How space is used is evolving, and making appropriate choices is critical, according to investor Siegel. But he warns against buying too deeply into the branchless concept. Consider Amazon and similar players, he says. Even if Amazon follows through on rumored plans to open many stores (one is open, so far), its main thrust will remain online. But that isn’t free, says Siegel. Such players spend as much on marketing to put themselves out there as physical stores spend on rent.

“You have to have a presence in people’s minds,” points out Siegel, and for the banks, that can still be a well-designed, well-run, well-sized, and well-placed branch.

Two companion articles to read:

• M&A: Looking to sell? Some expert tips

Tagged under Management, CSuite, Community Banking, M&A, Feature, Feature3,