Eye on multifamily CRE risk

As regulators scrutinize multifamily lending, banks balance demand with risk management

- |

- Written by Steve Cocheo

Both regulators and bankers have been watching the balance in the multifamily market.

Both regulators and bankers have been watching the balance in the multifamily market.

Signature Bank President and CEO Joe DePaolo grew up in a five-story walk-up in the Bronx. The New York City lender says there was never a vacancy in the building. The landlord always had a waiting list.

New York City’s five boroughs represent the largest multifamily rental market in the United States. Growing up, DePaolo learned an important lesson about that market, which $36.5 billion-assets Signature serves: “There’s never enough housing, at least for low-to-moderate and middle-class households. And there’s always a need for multifamily.” Nationally, a bit over one-third of housing stock consists of rentals of all kinds.

Many heads, fewer roofs

Nationally, rental housing vacancies have been declining, with quarterly blips, since 2009—a good thing for landlords and their lenders. The second quarter closed at a vacancy rate of 6.7% versus second-quarter 2009’s 10.6%. Regionally, the second quarter saw vacancies lowest in the Northeast (5.2%) and the West (4.9%), and highest in the South (8.9%) followed by the Midwest (7.3%).

In its second-quarter Multifamily Investment Outlook, advisory firm Jones Lang LaSalle IP, Inc., points out that a long-standing, post-crisis “homeownership bottleneck” is helping to maintain a stable and strong rental pool. This plus factors such as many millennials’ preference for urban lifestyles drive demand.

“Renter-occupied household formations have surpassed owner-occupied household formations for the past nine years running,” writes Jones Lang analyst Michael Morrone. He reports as well that sales of multifamily buildings may exceed 2015’s record-setting pace.

New apartment units under construction in New York are adding to the inventory there, as is the case in many other markets currently, as a combination of demographic and societal trends drive increased demand for rental housing.

Signature Bank doesn’t have a stake in the many projects around the city now. The bank does not do construction loans.

And “we’re not in the high-end rental market at all,” DePaolo explains. Signature prefers deals with proven cash flow, and that is something that established buildings, often with rent-controlled units, provide. Rent-controlled tenant populations are considered more stable than others, and there is also a built-in rent increase when units change hands.

One of the pluses Signature has is its veteran multifamily lending team, which has worked for the bank for nine years, and had extensive experience before that working in multifamily in the Northeast. For bank lenders, multifamily is often a relationship business, entailing more services than just lending.

“They know the players—not just the brokers,” says DePaolo. “Like they say about the races, ‘You need to know the jockey’.” But then there are also the racing officials.

Agencies press vigilance

Regulators have been warning banks about increasing commercial real estate exposure, including multifamily lending, in multiple ways.

Last December, federal regulators issued their “Statement on Prudent Risk Management for Commercial Real Estate Lending.” The document contained no new rules or guidance, but reminded bankers of all that the agencies have already issued.

Earlier this year in its Semiannual Risk Perspective for the spring, the Comptroller’s Office acknowledged that multifamily, while growing, remains a small share of total lending. However, OCC reported that multifamily has become a significant concentration—25% or more of capital—and a fast-growing loan category for more than one in seven banks with loan growth of 10% or more.

OCC noted that growth is strongest for banks between $1 billion and $10 billion. Federal Reserve figures indicate that banks and savings institutions hold 35% of outstanding multifamily debt, the remainder largely held by government-sponsored enterprises (43%), though GSEs have been slowing involvement.

In July, FDIC’s Northeast regional office held a teleconference for its banks on CRE and multifamily trends, covering patterns seen in real estate reports and FDIC statistics, as well as concerns for the future and a review of best practices.

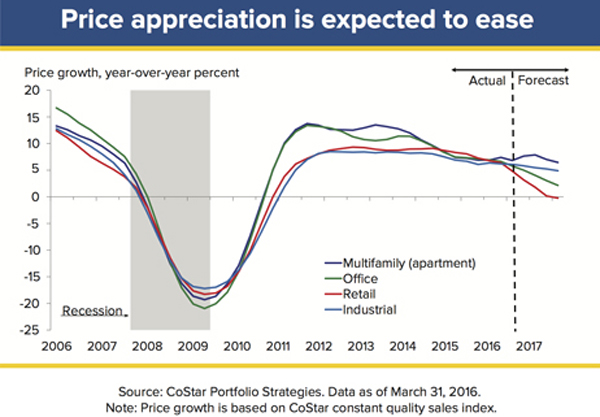

FDIC officials showed how New York region multifamily construction is swelling the supply, and pointed out how national figures compiled by CoStar Portfolio Strategy indicate that new units under construction are anticipated to exceed the market’s expected rate of absorption. FDIC warned that multifamily may be approaching supply-demand equilibrium, which could weaken prices, and that vacancy rates could rise.

Cream rises

For his part, DePaolo notes that seasoned, deeply committed multifamily lenders like Signature engage in a deeper level of analysis and stress testing than newer players. Experience, prudence—and regulatory expectations for heavily involved lenders—drive this.

In August, Keefe, Bruyette & Woods, recapping a community bank investor conference, noted how officers from northeastern lenders had spoken of the regulatory pressure:

“The consensus among management teams seemed to be that many of the more established multifamily and CRE underwriters have highly tested operations and detailed underwriting practices, which should allow them to take advantage of growth opportunities as certain other competitors may be pressured to pull back.”

Some pullback has been occurring already. There is speculation that some lenders, rather than devote more funds to stress testing and other controls, are voluntarily slowing down.

More evidence came in the JulyFederal Reserve Board’s Senior Loan Officer Opinion Survey on Bank Lending Practices. Overall, domestic bankers indicated that standards for all types of CRE loans have tightened, and more banks reported tightening than loosening. In multifamily lending, the survey indicated that 42.9% of domestic banks reporting had tightened, 47.1% had held steady, and 5.7% had tightened considerably; 4.3% had eased somewhat, and none had eased considerably.

Lenders address risk

Among banks presenting at the KBW conference, several have strong concentrations in multifamily, and they addressed regulatory issues and risk.

At $6 billion-assets Flushing Financial Corp., also in New York City, 42% of current originations are multifamily loans.

John Buran, president and CEO, said understanding the market necessitates “peeling back” what’s going on. He noted that Flushing Financial is not involved in the market-rent-based segment of multifamily.

Buran said this activity seems to be concerning regulators. Flushing Financial concentrates, he said, on the rent-regulated market, where rents average $1,300-$1,500, versus the $3,000 range for market-rent properties.

“We see the rent-regulated market as very stable going forward,” he said.

On the West Coast, $7.5 billion-assets Opus Bank makes multifamily loans in California (70% of its multifamily portfolio), Washington, Arizona, and Oregon.

“Opus underwrites multifamily loans at a ‘stressed’ underwriting rate that is higher than the start-rate of the loans,” according to the bank, “which provides greater protection to the loan’s debt service coverage.” The start-rate is the floor for the hybrid fixed-floating loans. (More on this later.)

Beyond credit risk

An interesting point that Opus brought up is that multifamily loans can qualify for 50% risk weighting, which permits a bank to hold less capital against qualifying loans.

Opus noted that multifamily loans have two sources of repayment—the property’s cash flow and recourse to the borrower, as guarantor for the property. At present, 44% of the bank’s multifamily loans qualify for that treatment.

Another factor is rate risk. While Opus, a relatively young bank, has become the major West Coast multifamily lender, Michael Allison, Opus co-president and president of its commercial bank, told the KBW conference that the bank has increased its emphasis on C&I loans. Multifamily credit, he said, is the bank’s lowest-yielding asset, and the bank has been growing business loans to enhance the bank’s yield. This is in spite of a loan structure that includes a floating-rate element.

At Opus, multifamily loans begin for a three- or five-year period at a fixed rate. Then the loan rate shifts to a floating rate indexed to LIBOR. Generally, final maturity runs ten or 15 years.

Signature Bank’s DePaolo reports a similar strategy—increasing C&I lending to increase diversity and to increase the portion of its loan portfolio that carries floating rates.

In a sense, today’s search for yield may drive the shift that regulators have been urging through exams and jawboning.

Tagged under Management, Lines of Business, Mortgage/CRE, Commercial, Feature, Feature3,