Marking Truth in Savings’ 25th year

Did TISA get it right?

- |

- Written by Mike Moebs

- |

- Comments: DISQUS_COMMENTS

Mike Moebs, "The Prairie Economist," believes the Truth in Savings Act is one of those banking laws that actually wound up working for everyone.

Mike Moebs, "The Prairie Economist," believes the Truth in Savings Act is one of those banking laws that actually wound up working for everyone.

Amid all the talk about the Trump Administration and what it will or won’t do about the Dodd-Frank Act, have we missed a milestone about a law and regulation that the industry fought for years before the FDIC Improvement Act finally thrust it onto the regulatory stage?

Dec. 19, 1991, President H.W. Bush signed the Truth-In-Savings Act (TISA) into law. Now, 25 years later, TISA (implemented by Federal Reserve Regulation DD in 1992) is considered by many regulators, consumer advocates, and bankers to be the most uniformly beneficial financial service law for both banks and consumers.

“Truth in Savings does seem to have withstood the test of time,” says Leonard Chanin, the attorney for the Federal Reserve who in 1992 turned TISA into an implementable regulation (Reg DD).

Many people I’ve talked to in researching how TISA got started and how it has worked over the past 25 years, called Chanin the “Architect of Truth in Savings.”

Chanin reminded me about Professor Richard Morse, an ardent supporter of Truth in Savings. Morse was a key figure in TISA’s passage. In 1991 Jane Bryant Quinn of The Washington Post Writers Group described Professor Morse in the context of Truth in Savings:

“On the Washington Mall, savers should erect a statue to Richard L.D. Morse, professor emeritus of Kansas State University. For almost 30 years, Professor Morse—the father of truth-in-savings legislation—has been badgering Congress…”

His badgering finally resulted in TISA’s passage. Let’s look at the result, a bit of truth in history of truth in savings.

1991’s checking and deposit culture

Moebs $ervices’ Survey in 1991 found the average “free checking” account charged a $3 monthly fee if the required $100 minimum balance was not maintained. In the following year, another Moebs survey found that only 3.1% of all financial institutions offered “free checking,” where the average overdraft fee was $15 per item.

The consumer knew free checking wasn’t really “free.”

Before TISA was implemented, many institutions did not uniformly disclose their fees or rates. Afterwards, the competition between depositories was welcomed, and so was the advertisement of these fees and rates to consumers.

Before TISA it was like pulling teeth to try to get a bank, thrift, or credit union to reveal what its overdraft price was.

What did TISA do?

Leonard Chanin has the best answer to this question:

“Regulation DD was the first federal rule to establish standardized disclosures and provisions for consumer deposit accounts. The rule created the concept of an “annual percentage yield,” (APY) which was the corollary to the annual percentage rate (APR) disclosed for loans.”

Specifically, TISA can be summarized as follows:

A. Every financial institution is required to disclose terms, rates, fees, and balance requirements on deposit accounts.

B. Definition of accounts features became standard. As an example, free checking:

1. No minimum balance requirements

2. No periodic fees of any kind

3. No transaction limitations

4. No conditions to get the account

C. There was a formula for calculating APY and a rate was the rate.

D. Prices for some services, such as overdrafts, were required to be disclosed.

The real plus of TISA is that it required only 10 pages of the 158-page FDIC Improvement Act of 1991, and Reg DD came to fewer than 100 pages in final form.

Remarkable when compared to laws and regs that followed. However, TISA and Reg DD were so well-crafted that it gave very clear direction of what was required.

The best description of TISA came from Chanin. “Unlike many other federal consumer financial laws and rules, Regulation DD remains fairly short and simple,” he says.

In the end, everyone wins.

What was the result?

Banks, thrifts, and credit unions fought TISA very hard after it was enacted.

However, the only major thing that TISA’s detractors achieved was minimizing penalties that were included in the original act—something that had never really been done before TISA. This was answered by examiners who put violations in exam reports, leading to delays in new branches and other matters.

The fight on TISA subsided when institutions starting making money from the uniformity and standardization brought about by the act. Along with the positive financial impact on institutions, the act also gave consumers more transparency and better understanding of the services being offered and prices charged.

Free checking and overdrafts provide measure of TISA

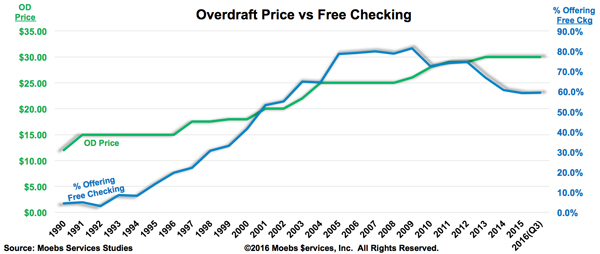

Moebs 1992 Study found free checking was being offered by 3.1% of all institutions. Since then, the number of institutions that offer this service has risen, hitting an all-time high of 81.5% in 2009.

Moebs Surveys have also found that historically a higher percentage of credit unions offer free checking than do banks. Today we see that only 50.5% of banks offer it, while 79.5% of credit unions do. This reinforces how banks and credit unions employ different strategies to succeed in the checking account marketplace.

There is also a significant connection between free checking and overdrafts. Bank overdraft revenue in 1992 was approximately $10.7 billion, increasing to $26.9 billion today, a compound annual growth rate of 3.8% a year. On the other hand, credit unions started out at $0.9 billion, growing to $6.1 billion today, a 7.6% growth rate per year.

Another true measure of the full benefit of Truth in Savings can be seen with inflation. According to the Minneapolis Federal Reserve Inflation Index, an overdraft fee in 1991 of $15 per item is equivalent to $25.59 today.

Currently only about one in four institutions offer overdraft fees below $25.59 per item. When taking size of an institution into consideration, nearly half of the small community institutions, below $100 million in assets, have OD fees less than $25.59 per item.

TISA had a significant impact on the consumer’s knowledge of banking services and fees. It also impacted the level of competition between depositories. TISA standardized and leveled the playing field by defining APY.

The significant impact of TISA on APY is easy to overlook in the light of the last eight years of record low rates. Nonetheless TISA remains a positive force for the consumer and marketplace.

What is TISA’s future?

Inevitably, adjustments have been made to TISA over the last 25 years, yet its core has stood the test of time. Currently, it would appear there is no major overhaul needed for TISA.

However, as in baseball, some tweaking with new rule changes improves the time-tested. One example would be a definition of using direct deposit as a requirement to get free checking, and an update to disclosures written at a junior high level of reading skill.

I asked Milton Friedman about TISA when it first was enacted. Friedman stated he did not believe in the regulation of services.

I then asked him if he believed in stop lights and stop signs. His response was classic: If the stop lights and signs improve the flow of commerce, then they could be useful.

It would appear Friedman—on this 25th anniversary of the Truth in Savings Act—might find TISA useful.

I find it a good regulation that has assisted consumers and financial institutions. Do you agree? Let me know in the comment space below.

Semper,

Mike Moebs

Mike will respond to questions at [email protected]

Related items

- Inflation Continues to Grow Impacting All Parts of the Economy

- Banking Exchange Hosts Expert on Lending Regulatory Compliance

- Merger & Acquisition Round Up: MidFirst Bank, Provident

- FinCEN Underestimates Time Required to File Suspicious Activity Report

- Retirement Planning Creates Discord Among Couples