Checking undergoes greatest shift since WWII

Role of accounts themselves—and competition’s appetites for relationships—is changing

- |

- Written by Mike Moebs

- |

- Comments: DISQUS_COMMENTS

In the first part of a three-part series, “Prairie Economist” Mike Moebs begins a discussion of how the operational and competitive aspects of checking have evolved.

In the first part of a three-part series, “Prairie Economist” Mike Moebs begins a discussion of how the operational and competitive aspects of checking have evolved.

At the end of World War II military service men and women came home and took advantage of two things: the G.I. Bill to pursue their college degrees and opening a checking account for the first time.

Today’s readers may be surprised by the second part of my opening. Leading up to WWII was the Great Depression. The average working Jane and Joe did not have a checking account. They were paid in cash at the end of the week.

WWII taught families the use of the “paycheck” instead of “pay envelope.” In response, financial institutions opened accounts for millions of first-time checking account holders and found the checking account became the gateway to auto loans, mortgages, and eventually credit cards.

In many ways, this was when the foundation of today’s consumer banking was poured.

Of course, much has changed since.

Moving money grows more technological

“Checking” is increasingly paperless, with plastic money in the form of debit cards dominating and even this stage competing with automatic deposits and withdrawals and electronic P2P payments via the likes of Zelle and Venmo.

Households in the third millennium use online and mobile banking to keep informed and conduct transactions. Meticulously filling in check registers or writing paper checks doesn’t fit with the Age of Apps.

Increasing competition from fintech firms—and even the likes of Walmart—are taking checking from traditional banks, thrifts, and credit unions. Interestingly, the motivations aren’t necessarily the same as banks’.

Economically, the checking account has increasingly become a key barometer and a personal economic hub account. How much money is in checking? How many transactions are done? What type of transactions? Who is making the transaction? And when? etc. The answers to these questions is directing the business of checking.

In this blog, the Prairie Economist analyzes some big data and outlines the macro and micro economic factors affecting checking—it’s a brave new world.

What checking account trends tell us

The consumer continues to be disengaged from retail and much of the economy. This fact comes from analyzing over 12,000 depository call reports and comparing them to the Federal Reserve’s monetary data for 2017.

The consumer in banks, thrifts, and credit unions by region, state, city, and asset size keeps warehousing more checking dollars. The average consumer checking balance has increased in 23 of the past 30 quarters. The average Joe and Jane remain very leery of the economy.

(You will not read this elsewhere, necessarily. Some write about rising consumer confidence. That is not what checking trends are telling me.)

Yet, the Federal Reserve keeps raising interest rates, and just affirmed its continuing plans to do so.

When economic times are good the consumer affirms this by keeping little in checking. Yet, when times are difficult the consumer stores money in checking, affirming that times are difficult and the consumer doesn’t spend.

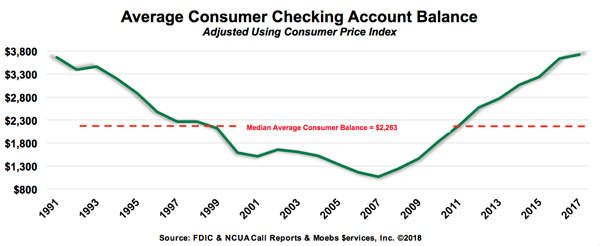

Examining the past 26 years, the consumer had the least amount of money in checking in 2007 (a year ending a period of strong economic growth), averaging less than $1,000. Since 2008 the consumer has hoarded money in checking.

Consumers, on average, have over $3,700 in checking, now which is the highest amount in U.S. history. (By the way, these average consumer checking balances have been adjusted for inflation, or the value of the dollar on deposit in financial institutions.)

The median amount a consumer had in their checking account since 1991 is $2,263. Anything lower than the median signifies the economy is doing well. Conversely anything above the median indicates the economy is not doing well.

Since 2008 the consumer has withdrawn from checking only what is necessary—and been very selective in large purchases.

The Fed’s own money supply numbers affirm the high balances. At the end of 2017, M1, the monetary measure of demand deposit accounts, including insured and reserved checking, stood at $2.108 trillion.

Normally, M1 would have about $700 billion in checking of all types. To define “normal,” consider this: Adjusting for inflation the period would very conservatively be 1996-2006, when M1 would have been $650 billion to $750 billion.

Non-interest DDA is about 75% of all checking, currently. Interest DDA is about 25%. In good economic times the split between DDA and interest-bearing DDA is 50%-50%.

Let me explain this. In difficult times more money will go into non-interest DDA. Reason: Consumers and small businesses want to carry big reserves to meet what they think the future will bring them. Non-interest DDA typically sits in free checking accounts, which generally have no balance requirements nor monthly fees as interest-bearing DDA does. So it is significant we have the 75%-25% split. Clearly, these customers don’t believe the economy is there yet.

Overlooked as a measure of economic activity, checking has nevertheless become a concurrent barometer of the economy. The Federal Reserve has testified to Congress the consumer comprises 70% or more of economic activity for the total economy. Checking is the medium of how the consumer’s economic activity is accomplished.

In my next installment, "Why Walmart likes checking," I look at how competition from nontraditional checking players affects, and will affect, the numbers we see concerning checking. My final installment will examine tactics that I believe banks should consider, depending in part on their overall strategies.

Semper,

Mike Moebs

(Mike will respond to questions at [email protected])

Tagged under Management, Lines of Business, Retail Banking, Blogs, Customers, The Prairie Economist,

Related items

- Inflation Continues to Grow Impacting All Parts of the Economy

- Merger & Acquisition Round Up: MidFirst Bank, Provident

- Retirement Planning Creates Discord Among Couples

- Wall Street Looks at Big Bank Earnings, but Regional Banks Tell the Story

- Economists Become More Optimistic About Credit Conditions