Retail, risk management evolution drives HR picture

Part 2: Supply, demand, and industry shifts repaint pay and employee bases

- |

- Written by Crowe Horwath Compensation Study

For the third year we present exclusive reports on this website from Crowe Horwath LLP from its annual Financial Institutions Compensation and Benefits Survey. To review last year’s series and recommendations, see Crowe Horwath Compensation Study.

The years since 2008 have seen great—some might say unprecedented—pressures on financial institutions. A sudden economic downturn accompanied by a fast-changing and fast-growing regulatory environment has made the banking industry of 2014 very different from the industry of 2008.

One way these changes can be seen is in the changing value that financial institutions place on various jobs that must be performed. Many of these changing values are reflected in the compensation trends recorded in the annual Crowe Horwath LLP Financial Institutions Compensation and Benefits Survey, which queries financial institutions throughout the U.S. about compensation trends, benefits, incentives, and other human resource issues. This article is the second in a series exploring results from the 2014 survey.

By comparing this year’s survey results to those of the previous six years, it is possible to note some instructive trends—in terms not only of how the recession affected pay and other benefits but also of how banks’ priorities and concerns have shifted.

Supply and demand in a changing economy

The law of supply and demand is only one of many factors affecting pay and compensation trends, but its impact is indisputable. To cite an obvious example, supply and demand is one reason why a CEO earns more than a teller. Many other factors affect the relative pay scales, particularly the relative levels of responsibility in the two positions and the role each position plays in affecting the overall performance and value of the institution.

The fact remains that the supply of people who can capably perform a teller’s duties is much greater than the supply of people qualified to serve as CEO, and the relative pay scales of the two positions reflect this simple truth.

Compensation is not the only way in which the law of supply and demand manifests itself, and it is not necessarily the most instructive factor to study. Changes in the number of people performing certain tasks also can provide insight into how banks have responded to recent economic pressures.

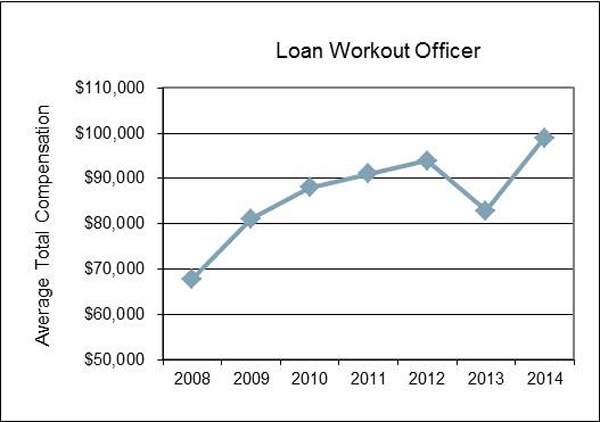

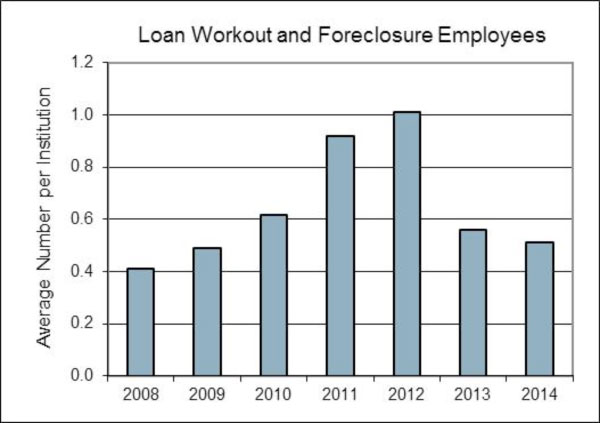

For example, as financial institutions struggled to manage the surge in problem or nonperforming loans and the financial and capitalization issues such loans caused, the demand increased for people who could help work out problem loans, and salaries went up as a result.

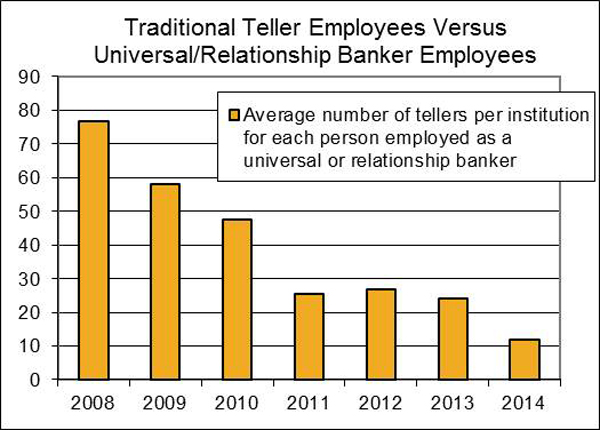

The first chart in Exhibit 1 tracks the average number of employees in each institution who hold positions with titles such as loan workout officer or manager, special assets officer or manager, foreclosure supervisor, or comparable descriptions.

Exhibit 1

Readers must avoid using the staffing levels in the survey as a point of direct comparison to their own institutions. The survey participants range in size from community banks with assets below $250 million all the way up to large national institutions with many billions in assets. Staffing levels obviously vary greatly according to institution size.

Bearing that precaution in mind, it is nevertheless possible to see how the demand for people to fill loan workout positions shifted during the course of the recession, peaking in 2012 before starting to pull back.

The second, right-hand chart in Exhibit 1 shows how compensation reflects changes in demand. Although some of the year-to-year fluctuations illustrated in the exhibit are at least partially attributable to changes in the makeup of the survey population from one year to the next, the total average compensation for loan workout officers ultimately increased by 46% from 2008 to 2014.

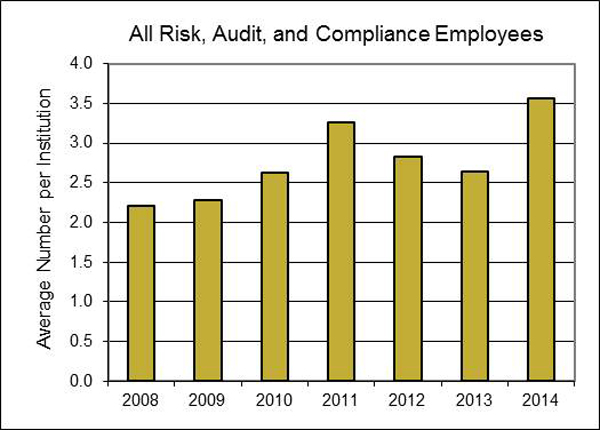

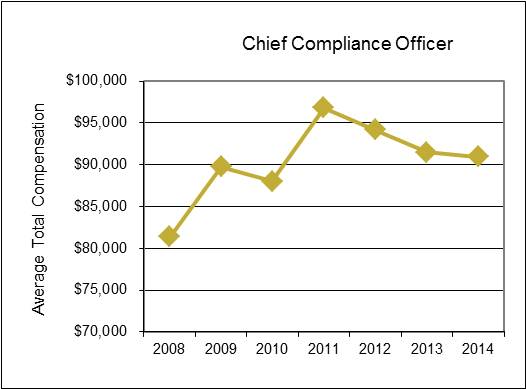

A similar trend can be seen in the area of risk management and regulatory compliance. Exhibit 2 tracks the average total number of positions related to risk and compliance per institution. The industry’s initial reaction to passage of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act in mid-2010 clearly is visible. Subsequent peaks in demand appear to correspond to the rollout of various reporting deadlines for new rules from the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau and other regulators.

Exhibit 2

Again, compensation for risk-related positions, such as chief compliance officer, corresponds generally with the change in demand. As was the case with loan workout officers, some of the year-to-year fluctuations likely reflect changes in the makeup of the survey population. Nevertheless, the general upward patterns of both population and compensation are evident.

Supply and demand reflects changing industry

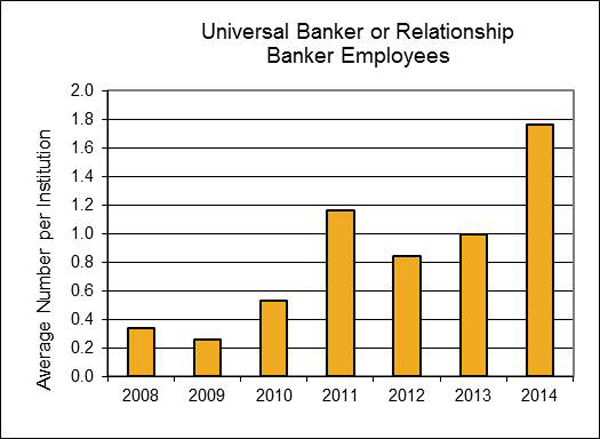

The economy and regulatory environment are not the only forces that affect supply and demand in banking industry employment. Technological advances and changes in banks’ overall operating methods also can be seen in the survey results.

This is particularly noticeable in branch operations, as electronic and mobile banking technology reduce customer traffic in branches. The number of people employed in traditional branch positions appears to be slowly declining, but there has been a sharp increase in the average number of people holding jobs described as universal banker or relationship banker.

Exhibit 3

Tellers still outnumber universal bankers by a large margin, but the ratio has narrowed significantly. In 2008, the survey reported an average of 26.11 tellers per institution, compared to an average of only 0.34 universal or relationship bankers per institution—a ratio of more than 76-to-1.

By 2014, the average number of tellers had declined to 21.08 per institution, but the average number of universal bankers per institution had more than quadrupled. As a result, the ratio of tellers to universal bankers shrank to less than 12-to-1.

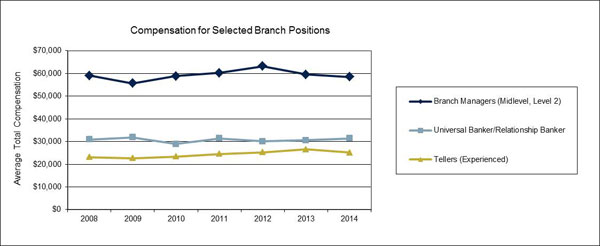

Interestingly, however, these changes in branch staffing strategies are not clearly reflected in the average compensation for representative positions, which have remained relatively stagnant for both the teller and universal banker jobs as well as the branch manager position, as seen in Exhibit 4.

Exhibit 4

For a larger version, click on the image.

For a larger version, click on the image.

One possible explanation for this lack of salary growth is that the newly created universal banker positions most likely are being filled from within the ranks of experienced tellers. This practice ensures a steady supply of candidates to keep up with the growing demand.

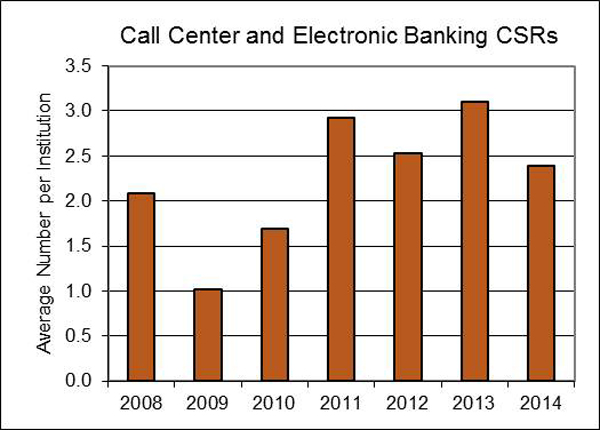

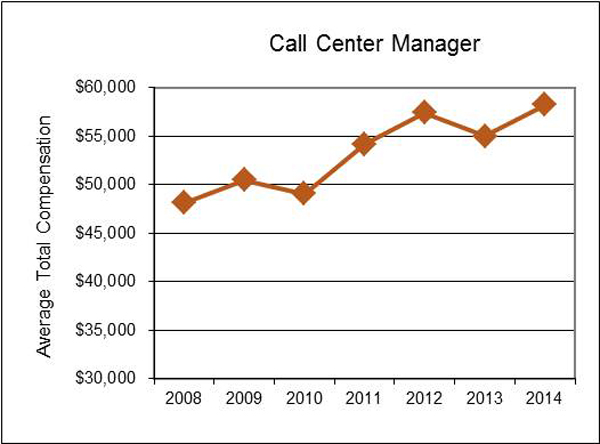

The 2014 survey also demonstrates the effects of rapidly growing use of electronic banking and other new technology. As in-person interactions for routine transactions decline, the need for call center and electronic banking customer service representatives has grown. Not coincidentally, total average compensation for call center managers increased by 21% over the past six years.

Exhibit 5

Where trends point

In a sense, the changes seen in the annual compensation and benefits survey could be viewed as the outcomes of the supply and demand equation. But rather than focusing on the outcomes, there is more insight to be gained by studying the inputs into that equation—that is, the changing demands for specific job skills.

The ultimate question, of course, is how to put this information to work. The next article in this series will begin to address that question, as it discusses how financial institutions can go about aligning their compensation levels and strategies to match market forces.

Tagged under Human Resources, Management, CSuite,