What you see, what you say

Lending with your eyes open, mouth in control, brain in gear

- |

- Written by Ed O’Leary

- |

- Comments: DISQUS_COMMENTS

“There’s really not much that indicates we’ve learned anything new over the last several cycles,” says veteran lender and CEO Ed O’Leary. Each week in his blog he strives to fix that.

“There’s really not much that indicates we’ve learned anything new over the last several cycles,” says veteran lender and CEO Ed O’Leary. Each week in his blog he strives to fix that.

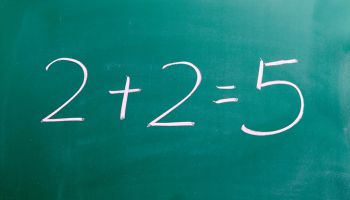

Recent news contained two items worthy of attention by lenders. Both prompt thoughts relating to lender behavior. One deals with the deal that doesn’t add up, and the other concerns where the line is, today, between being a helpful banker and stepping over the line.

Does a deal violate what you know and trust?

The first news story related to Volkswagen’s software installed on at least 11 million diesel cars manufactured by the company in recent years. Volkswagen has admitted to the use of software during periods of testing that dramatically understated the true level of diesel engine emissions under normal operating conditions.

While internal investigations are only now getting underway, it appears that the express purpose of the software modification was to significantly boost sales of smaller Volkswagen automobiles equipped with diesel engines. Volkswagen is currently the world’s second-largest automotive manufacturer with 2014 production of 10,140 units manufactured behind Toyota’s annual production of 10,230 units during the same period.

The significant item that caught my eye was the almost certain knowledge by diesel engineers that the task of producing results on small cars as VW was reporting was virtually impossible.

Diesel engines work optimally on big vehicles, trucks, construction equipment, and the like. They operate at lower RPMs and have no operational advantage on smaller vehicles. Gasoline engines produce peppier performance with cleaner emissions.

While you or I might not know such things, the engineers at VW are truly “car people” who understand the physical constraints. That suggests that VW’s actions were cold, calculated, and hidden in plain view. But the relevance to lenders and applicable to a huge array of credit situations is the insight that the mileage and emission results were counterintuitive and they should have been questioned or disputed almost immediately.

How many lenders have puzzled over a credit proposal or a set of circumstances that just didn’t make sense?

When I was a very junior lender in The Bank of New York’s metropolitan lending division I was introduced to a prospect who operated a non-technical basic metal fabricating business. It was dirty, low-margin work. But he appeared to be profitable and had the equivalent of a review set of financial statements.

Something wasn’t right about the way the numbers came together.

But I never went further with my doubts or my uncertainty.

We declined to pursue the loan based on the degree of reported leverage. I subsequently learned more than a year later from the person who referred the opportunity to us that the principal had been cooking the books and that a bank in New Jersey suffered a significant loss.

That could have been a very embarrassing lapse.

I did the right thing but for the wrong reason. Something seemed wrong and I turned a blind eye.

Volkswagen’s claims on emissions were stellar on their face but anyone with an engineering background and with knowledge of diesel engines could have sensed something was amiss. In fact there was, and we now learn that some outside the company questioned the accuracy and authenticity of the reported results.

Lesson for lenders? “Eyes wide open” is just the first step. Acting on what you see completes the loop.

Advice versus compulsion

The other news item that I spotted recently involved an appeal of a Delaware Supreme Court case where Royal Bank of Canada’s investment banking arm was found liable of giving improper merger-related advice to one of its clients. A lawsuit that was concluded over a year ago resulted in a judgment against RBC of $100 million over an investment banking fee charged of $4.5 million.

The issues of the dispute are not the point here nor is the fact that this is not the first time that investment bankers have been accused of conflicts of interest relating to the business that they conduct.

While the court has taken up the review of RBC’s appeal of the $100 million judgment, it has not yet been resolved. If RBC loses its appeal and is liable for the full amount of the judgment, I predict it will produce another spate of legal concerns about banks and bankers rendering advice to clients.

The granddaddy of a branch of law now referred to as lender liability arose in the 1970s. A lender to Farah Manufacturing of El Paso was accused of improper meddling in the internal affairs of a troubled borrower. At issue were actions taken by the bank pursuant to later disputed terms of a loan agreement, whereby the bank forced a change of control in the management and governance of the company. The results of this change were disastrous in the business sense and the bank was sued and lost.

The narrative of the old Farah case is not of concern to us today, but the lesson is.

What I remember so clearly was the knee-jerk reaction of bank lawyers, coast to coast, who advised their clients to refrain from giving any business advice to borrowers.

The concern was that if the borrower was compelled by the bank to act on the bank’s advice and the result turned out poorly, the bank would incur potentially significant liability for the consequences. The issue hinged on whether the bank compelled or forced the company to undertake a particular course of action.

Conservative bankers and their legal counsel who were stunned at the size of the award to Farah shut down anything approaching any advice or counsel by lenders to their customers.

This chilled a generation of information sharing and advice between lenders and borrowers. That freeze denied borrowers access to useful and helpful business counsel. We’ve largely gotten over that excessive caution.

However, if RBC loses its appeal, we may face years of a reaction and a posture similar to the aftermath of the Farah case.

We are deep into a period of a rigid compliance mentality fostered by Dodd-Frank and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. Our industry does not need a further overreaction of examiners and bank lawyers.

Customer service and new business generation have suffered enough from the consequences of chronic overreaction in the last several years.

Tagged under Risk Management, Blogs, Talking Credit, Credit Risk,